By Eileen Wingard

SAN DIEGO — With a Jewish soloist, violinist Pinchas Zukerman, in the first half of the program and a tone poem by a Jewish composer, Arnold Schoenberg, in the second half, last Sunday’s San Diego Symphony concert seemed tailored for this Jewish holiday season.

The Tel Aviv-born violinist, Pinchas Zukerman, now in his fifth decade of concertizing, and with over 100 recordings to his credit, was a last-minute replacement for the originally scheduled Armenian violinist, Sergey Khachatryan, who confronted visa problems. The change was made too late for the deadline of the San Diego Union Tribune, which, unfortunately, continued to advertise the originally programmed soloist playing the Brahms Violin Concerto.

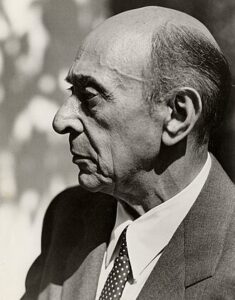

(Photo: Paul LaBelle)

Instead, Zukerman opened the program with the Beethoven Violin Concerto. The San Diego Symphony Orchestra provided a sensitive accompaniment under Raphael Payare’s baton, and Zukerman’s effortless playing, transparent in its clarity and iridescent beauty, simply floated to our ears in the improved acoustics of the renovated Jacobs Music Center.

This is a concerto of great lyricism. Its opening is unusual, five soft timpani strokes. The first movement elaborates on two simple themes and it is only in the cadenza where the violinist can display his great technical prowess. With a series of breakneck speed scales, arpeggios, double stops and chords, Zukerman did just that.

The sublime second movement was a theme and variations accompanied by muted strings.

In the finale movement, Zukerman gave just the right lilt to the rondo theme and basked in the enchanting episode where violin and bassoon intertwine.

Zukerman plays on the “Dushkin” Guarnerius del Gesu violin. Samuel Dushkin, the previous owner, was a New York-based violinist and composer whose arrangements of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella Suite and music by the Jewish composer, Paul Kirman, were recorded by my sister, violinist Zina Schiff.

Samuel Dushkin’s brother, Alexander Dushkin, an amateur cellist, was the head of the Education Department of the Hebrew University when my husband, Hal, three-year-old daughter, Myla, and I stayed with his family in Beit Yanai during our Summer 1961 visit to Israel. I played violin-cello duets with Alexander and we were welcomed into his home because of our friendship with his daughter, Avima Dushkin Lombard and her husband, Emanuel Lombard. So, learning that Zukerman played the “Dushkin” Guarnerius del Gesu had special significance for me.

After intermission, an enormous orchestra assembled on stage for the performance of Arnold Schoenberg’s tone poem, Palleas and Melisande.

Although when I entered UCLA in Fall of 1947, composer Arnold Schoenberg’s eight-year tenure of teaching at the university had ended, my harmony teacher during my freshman year, Natalie Limonick, had studied with him, used his materials and frequently spoke about him. In later years, I performed and attended concerts in Schoenberg Hall, the campus music hall named in his honor, so he was an ever-present identity in the UCLA Music Department.

Schoenberg was one of the many Jewish refugees in Los Angeles. He escaped after being fired from his post at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin where he had served since 1925. He came to the United States in 1933.

Although I was exposed to Schoenberg’s music, I had never heard his tone poem, Pelleas and Melisande before. This epic work was composed before Schoenberg’s atonal and tone row period and is heavily influenced by the music of Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, his two mentors, as well as by Brahms and Wagner. The orchestra he uses has additional woodwinds, brass and percussion which he utilizes to tell the tale, based on the play by the Belgian playwright, Maurice Maeterlinck. The work is played without pause but is actually divided into four movements.

Texts were projected to assist the listeners to understand what the programmatic music wanted to convey. There were distinct motifs for the three characters, the older prince, Goulad, with a noble horn theme, the maiden he meets in the forest, Melisande, described by a plaintive oboe melody, and his younger half-brother, Palleas, represented by an angular trumpet theme. There was also the four-note “Fate” motif, played first by the bass clarinet.

The first movement is in sonata-allegro form, describing the forest where Goulad discovers Melisande, their marriage, his introducing her to Palleas and the awakening love between Palleas and Melisande.

The second movement is a Scherzo and depicts her and Palleas at a fountain where she playfully tosses her wedding ring in the water. It also conveys a scene where she is in a tower with her hair hanging down and another where Goulad is leading Palleas through the catacombs of the castle.

The third movement expands on the love between the two younger characters, and Goulad’s slaying of his half-brother.

The final movement brings the death of Melisande. Themes are brought back from the beginning including many repetitions of the “Fate” motif and it ends darkly.

There were many notable solos by the principal strings, the principal winds and the principal brass, confirming the high level of musicianship of our San Diego Symphony players.

Gerard McBurney, who has joined the San Diego Symphony as Artistic Consultant, delivered the pre-concert lecture. He told about Schoenberg’s younger son, Lawrence, and his wife coming down from Los Angeles to hear this performance of his father’s work, and how pleased and impressed they were with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra’s interpretation.

With a world class soloist, violinist Pinchas Zukerman, and our great orchestra playing a tone poem by Arnold Schoenberg, one of the 20th century’s most influential composers, it was a memorable concert experience.

*

Eileen Wingard, a retired violinist with the San Diego Symphony, is a freelance writer specializing in coverage of the arts.

Emanuel was my father.