By Alex Gordon

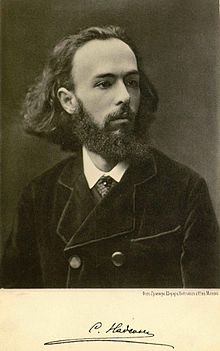

HAIFA, Israel — The poet Semyon Nadson (1862 – 1887) lived for 24 years. He is known for being the first poet of Jewish descent to achieve national prominence in the Russian Empire. In 1886, Nadson was awarded the Pushkin Prize of the Academy of Sciences, the most prestigious literary award in pre-revolutionary Russia.

His poetry was admired by the famous poets Alexei Plescheyev, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Igor Severyanin, and Valery Bryusov. Famous composers Sergei Rachmaninoff and Anton Rubinstein wrote music to his poems. More than 100 of his poems are set to music. When Nadson’s death became known in January 1887, the famous writer Anton Chekhov responded to the news in a letter to Nikolai Leikin, a writer and publisher, as follows: “Nadson is a poet far greater than all modern poets put together.”

The poet’s father, baptized Jew Yakov Nadson, was a high-ranking clerk, equivalent to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the army. He died when the boy was two years old. His mother, Russian noblewoman Antonina Mamontova, died of tuberculosis when Semyon was ten years old. He was brought up in his mother’s family. His uncle Ilya Mamontov was an antisemite who believed that “the shameful stain of Jewishness he [his nephew] can wash away only by military service, for him this is the only way out.” Semyon was burdened by the tutelage of his Judeophobic relatives and their desire to force him to serve in the army. He called the military craft the art of “killing people according to the rules” and declared, “I hate the so-called military sciences.”

“When in me, a child, suffered an offended sense of justice” – he wrote in his diary in 1880 – “and I, alone, defenseless in a strange family, bitterly and helplessly cried, they said to me: ‘Again begins the Jewish comedy’ – c inhuman cruelty, insulting in me the memory of my father.” These words especially acutely hurt the boy “with a sensitive, painfully sensitive soul,” he had a “heart bursting with anguish,” and he intended to commit suicide. “I will throw in your eyes what boiled up in my sick soul,” he called out to his breadwinners,” and if you have a spark of conscience and justice, […] you will realize that the matter smells no longer a comedy, not a Jewish comedy, but a heavy, unbearably heavy drama!… It’s not the damned money I need – I need feelings, support, trust in me, respect for the memory of my deceased relatives!”

In 1879, at the insistence of his guardian Ilya Mamontov, Nadson entered the Pavlovsk Infantry Military School in St. Petersburg. Soon he caught a cold at the school, and doctors recognized the onset of tuberculosis. At the expense of the state Nadson was sent to Tiflis, where he spent a year. During this time, the poet wrote many poems. In the fall of 1880 Nadson returned to the school. Staying at the school he was burdened: “Military service is disgusting, a good officer I will never be, my hotness and inability to restrain myself will bring me to trial, I cannot do well, too: is it worth spending time and effort to study the science of killing people! But these powers and abilities could be developed and bring benefit! […] Actually, my dreams are a university or a conservatory. I have enough abilities, in hunting, too, there is no shortage. But I have to prepare for university, which again requires money, and I can go to the conservatory as it is. I would gladly go even to the music department of the theater school, especially since you can get there at public expense. In short, anywhere – but not military service! It is unbearably disgusting to me and goes completely at odds with my character and abilities.

After the wave of terrible anti-Jewish pogroms of 1881 – 1883 in the Russian Empire, the first time in the history of antisemitism organized by the government, Nadson wrote a masterpiece poem full of love for the Jewish people (1885):

I grew up a stranger to you, outcast nation,

And it was not to you that I sang in my moments of inspiration.

The world of your legends, your sorrow.

I am as alien to you as I am to your teachings.

If you had been happy and strong as of old,

If you had not been humiliated by the whole world.

If you had not been warmed and carried away by a different ambition,

I would not have come to you with a greeting.

But in these days, when, under the burden of sorrow.

You bend your brow and wait in vain for salvation,

In these days when the mere name “Jew”

is a symbol of rejection in the mouth of the mob,

When your enemies, like a pack of ravenous dogs,

They tear you to pieces, cursing at you, –

Let me humbly join the ranks of your fighters,

O people who have been wronged by fate!

This poem shocked the Jews of Russia. Vasily Lvov-Rogachevsky, a historian of Russian and Russian-language literature and author of the book Russian-Jewish Literature, wrote that in these lines “the voice of blood sounds loudly.” After this publication, Nadson began writing weekly feuilletons full of contempt for antisemites. His protests provoked rude attacks from the famous Russian writer Ivan Goncharov: “These are various Weinbergs, Frugs, Nadsons, Minsky… and others. They are cosmopolitan Jews, maybe baptized, but still remained Jews in flesh and blood… They could not perceive Christianity with their souls; Jewish fathers and grandfathers could not educate their children and grandchildren in the traditions of Christ’s faith, which is inherited first in the family life, from parents, and then developed and strengthened by teaching, preaching of instructors and, finally, by the whole structure of life in Christian society.”

Lvov-Rogachevsky called Nadson an “assimilated bard” who “was infected with the pain of the Jewish people.” The response to Nadson’s feuilletons was followed by, in Lvov-Rogachevsky’s words, “a camouflaged journalistic pogrom by Judeophobic authors.” Weakened by tuberculosis, the poet died from antisemitic attacks. Anton Chekhov called Nadson’s death a “murder.” On the day of Nadson’s funeral, he wrote to his brother Alexander: “Public opinion is offended by Nadson’s murder.”

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.