By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — The revolutionary impulses of the Jews of Germany disappeared with their community, destroyed by the Nazis. But reformist ideas remained and were concentrated in the teachings of the philosophical and sociological Frankfurt School, founded in 1923 by German-speaking Jews György Lukács, Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Erich Fromm, Wilhelm Reich, and Herbert Marcuse, who fled the Nazis abroad in 1933. This doctrine had no national forms, although it undoubtedly grew out of classical German philosophy. Its main tenets were a total critique of Western culture, Christianity, capitalism, tradition, sexual restrictions, family loyalty, patriotism, nationalism, and conservatism.

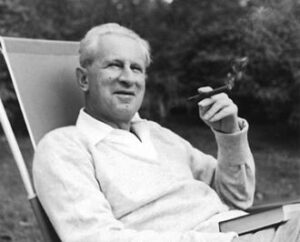

A major contribution to the ideas of the Frankfurt School was made by its youngest representative, Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), a member of the Berlin Soldiers’ Council, a member of the German Army during World War I, who took part in the November Revolution of 1918 and in the socialist uprising of the “Spartacus Union” (the future Communist Party of Germany). Marcuse was born into an assimilated Jewish family. After the Nazis came to power in Germany, he emigrated to Switzerland and then to the United States. From 1940-50 he worked for the Office of Strategic Services and the State Department. Since 1950, Marcuse devoted himself fully to academic teaching as a professor at Columbia, Harvard, Brandeis, and the University of California-San Diego.

According to Marcuse, only the “outsiders” who, unlike the proletariat, are not integrated into the existing social structure – the unemployed, the declassified, the lumpen, the young people disillusioned with the ideals and values of their fathers, and the peoples of the Third World – are capable of remaking Western society. Marcuse tolerated the use of violence against a “repressive” society. Like other theorists of the New Left, he appealed to the young revolutionary intelligentsia capable of understanding “the viciousness of the imperialist consumer society.” He pinned his hopes on oppressed colored, national, racial minorities, guest workers, the unemployed, gays, lesbians and feminists who could not fit into the “welfare society.” He staked the positive role of the “Third World,” that colossal global outsider of the world suffering from imperialism, wars, hunger, underdevelopment, economic exploitation by the Western “golden billion” countries. Marcuse contrasted the “Third World” with the Western “First World” inhabited by the middle class, a fed-up bourgeois “complacent herd.”

Marcuse emphasized Marx’s mistake: the material impoverishment of the proletariat did not occur, and he replaced it with the spiritual impoverishment of society under capitalism and the birth of “one-dimensional man” in his book One-Dimensional Man (1964). Marcuse argued that the proletariat had become socially insignificant compared to its role in the 19th century, for the “slave of industrial civilization” is not a proletarian but a consumer. The revolutionary-critical dimension of the man of the industrial “consumer society” disappears. He becomes a man of one dimension given by the “consumer society.” The one-dimensional man and the class consisting of such people became the backbone of the existing system.

Marcuse absolutized the shortcomings of the society in which he lived. By “one-dimensional society” he meant the United States, where he found himself after fleeing Nazi Germany. The demonization of the US, which is so popular today, led him to underestimate the power of dictatorship, particularly of the left, over the individual. He did not live in a totalitarian state and did not experience the monstrous power of the state over the individual.

Criticism of bourgeois society and apologia of freedom from its orders attracted leftist rebels to Herbert Marcuse’s ideology in the sixties and seventies of the twentieth century, but the “consumption” of Marcuse’s ideas, directed against the well-being of one-dimensional philistines of the “consumer society,” broadens the scope of the philosopher’s protest. Along with the leftists, Marcuse’s doctrine is quite capable of attracting right-wing “outsiders,” that is, not only those who are oppressed by the excessive, in Marcuse’s opinion, unfreedom of Western society, but also those who hate its “excessive” freedom. The extreme leftist author of One-Dimensional Man criticizes excessive conservatism, nationalism, and the overreach of religion in a “one-dimensional society.”

Herbert Marcuse’s theory is a great success in all three worlds. Western values provoke protest and a desire to level them on both the left and the right. In particular, “progressive” national, racial minorities and immigrants fight for their rights and try to grab more and more pieces of the national pie in foreign countries, i.e. to become part of the reactionary, according to Marcuse, “consumer society.” The “outsiders” of the Third World, belonging to extremist religious and national movements, fight for the destruction of Western civilization, that is, the system that feeds and sustains most of humanity, including them.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books