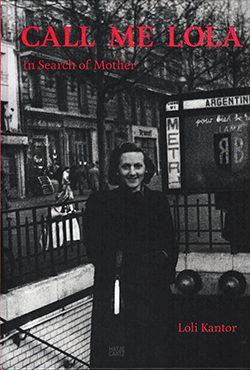

Call Me Lola: In Search of Mother by Loli Kantor; Berlin, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH publisher; © 2024; ISBN 9783775-75744; 225 pages, mostly photography, plus appendices; $62.

SAN DIEGO – Two hours after Lola Kantor was born, her mother died of complications in childbirth. Lola was given her mother’s first name, but, of course, she had no memory of her. Neither did she have any grandparents; they were all murdered in the Holocaust. Then at age 14, she was orphaned by the death of her father, Zwi. Her brother Ami had been a preschooler when their mother died, so his memories of her were hazy at best. And Ami died at age 50 in Munich, Germany.

SAN DIEGO – Two hours after Lola Kantor was born, her mother died of complications in childbirth. Lola was given her mother’s first name, but, of course, she had no memory of her. Neither did she have any grandparents; they were all murdered in the Holocaust. Then at age 14, she was orphaned by the death of her father, Zwi. Her brother Ami had been a preschooler when their mother died, so his memories of her were hazy at best. And Ami died at age 50 in Munich, Germany.

In midlife, Kantor turned from a career as a physical therapist to professional photographer, not only to engage her creativity but also to build a sense of connection to her mother and namesake. She discovered records that her father had kept of her mother. There was her mother’s Israeli passport with a French visa. A French document noting that on on January 22, 1952, her mother had given birth to a girl. She also found certification by Israel’s consulate in Paris of her mother’s death. Yet another document was an inventory from the Rothschild Hospital of the belongings her mother had brought with her to the hospital. Besides clothing, her mother’s possessions had included a silver metal chain, a yellow metal wedding band, a pearl necklace, a wristwatch, 612 francs, a handbag, powder box, wallet, cardholder, a flask of cologne water, and a box of Nives cream.

These records made an impact on Kantor; they documented the briefest of time when she and her mother were both alive, breathing the same air. She photographed these documents as well as another, a false German identification of her mother not as a Polish Jew but as a Polish Catholic girl named Jadwuga Kozlowski – a counterfeit so good, it kept her alive during the Holocaust. The Identification even included her mother’s real fingerprints. Post-war photos showed her mother and father as a newly married couple hiking in Germany and lighting Shabbat candles, and later enjoying life in Netanya, Israel, where they swam in the ocean, played with a dog, and celebrated Ami’s birth in 1948.

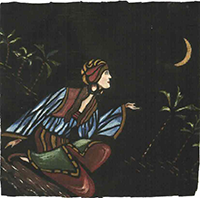

To these photos, Kantor added some of her own in 2015 to retrace her mother’s journey. There were photos of the Rothschild Hospital where one Lola’s life began and another Lola’s ended. That same year, she traveled to her mother’s hometown of Bochnia, Poland. She made several trips to such Eastern European venues as Lublin, Poland, and Lviv, Ukraine, and took deliberately blurry photos, impressions, I assume, of the haziness of her mother’s imposter life as Jadwuga. The cover of this book shows her mother in 1951 at the Argentine metro station in Paris; In 2019 Kantor found the same spot and posed similarly. She also took photos of her parents’ first home in Israel, and she curated photos of herself and brother Ami growing up. At an elderly aunt’s house she found a fanciful Arabian Nights painting done by her mother of a woman on a flying carpet passing over an oasis.

These and other photos are sandwiched between an introductory essay by Nissan N. Perez, a former senior curator of photography at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and the transcript of a conversation that Kantor has with her daughter Danna Heller, the director in the United Kingdom for Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Today, Kantor lives in Fort Worth, Texas, where she has the satisfaction that a wide range of photographic enthusiasts will know something about her mother, but the frustration that there’s more that perhaps will never be learned.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.