By Alex Gordon

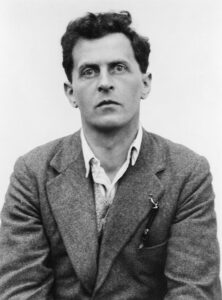

HAIFA, Israel — Ludwig Wittgenstein, Austrian-British philosopher and logician, was born on April 26, 1889, in Vienna, the son of Jewish steel magnate Carl Wittgenstein. His parents were baptized. He was the youngest of eight children. By the end of the 19th century, the Wittgensteins were one of the wealthiest families in Austria-Hungary. The Wittgenstein mansion was one of the centers of cultural life in Vienna: it was visited by the composers Gustav Mahler and Johannes Brahms and the painter Gustav Klimt, who painted a portrait of Ludwig’s sister Margaret in 1905. There were seven grand pianos in the house and all the children in the family were involved in music. Ludwig himself had an absolute musical ear and was going to become a conductor.

At the age of 14, Ludwig left his parents’ home to attend a real gymnasium in Linz, where his fellow student was Adolf Schicklgruber, the future Hitler, who was born six days earlier than Wittgenstein. Although the Wittgenstein family had converted to Christianity, they were considered Jews throughout the neighborhood. Therefore, the appearance of a Jew in the classroom provoked the ill-will of his classmates and the hatred of Hitler. “This Jew we did not particularly trust, […] we doubted his trustworthiness,” Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf. Wittgenstein was a truth-teller, which made his fellow students, especially Hitler, very angry: “A boy who stealthily follows his comrades commits treason, […] which is no different from treason against the motherland. He can by no means be considered good and decent, […] he is a little snitch from whom a great scoundrel will grow.”

Hitler’s special hostility to Wittgenstein is explained by a great envy: Ludwig came from one of the richest families in Austria-Hungary, was the most talented student, a well-rounded man of independent views, not submissive and opposed to the crowd. Apparently, Hitler associated all these alien qualities with Jewishness. Wittgenstein may have been the starting point of the monstrous anti-Semitism of the future Nazi Führer.

Wittgenstein was educated at the Hochschule für Technische in Berlin and at Victoria University in Manchester. He became an engineer, but under the influence of Gottlob Frege, the German logician, mathematician and philosopher began to socialize at Cambridge with the British mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, later winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. In time, teacher and student became friends. Russell wrote of Wittgenstein: “He was perhaps the most remarkable specimen of a man of genius – creative, focused, passionate, thorough, and prone to dominance. […] His interest in philosophy is more passionate than mine; compared to the avalanche of his thoughts, my thoughts are some pathetic snowballs.”

In 1913 he returned to Austria. In the same year his father died, and, having received an inheritance, Wittgenstein became one of the richest men in Europe. He anonymously donated large sums to Austrian architects, artists and writers. In 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, despite being released for health reasons, he volunteered for the active army. In March 1916, he was assigned to a combat unit on the Russian front, where his unit participated in the heaviest fighting. Throughout the war, Wittgenstein maintained a correspondence with Bertrand Russell.

So, as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army, he corresponded with a subject of a hostile state: working to solve logical problems was far more important to him than politics or patriotism. During his time in combat and in a prisoner-of-war camp, Wittgenstein wrote an almost complete Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which later became one of the most important works of philosophy of the 20th century. Returning briefly from the front in the summer of 1918, Wittgenstein attempted to publish The Tractatus, but a publisher refused to print the book. He returned to the Italian front, where he was taken prisoner in November 1918.

Returning to Austria in 1919, Wittgenstein renounced his share of the inheritance in favor of his siblings, as he considered money a hindrance to philosophical activity, following Spinoza’s example. Wittgenstein published Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1921 in German and in 1922 in English. The appearance of this work made a great impression on the philosophical world and caused numerous discussions, in which the author of The Tractatus did not participate, as he apparently believed that he had presented the solution to all philosophical problems.

He argued that from the point of view of logic the statements “there is God” and “there is no God” are equally meaningless, but nevertheless The Tractatus ends with the phrase: “What cannot be spoken of, must be kept silent,” which implies the existence of mystical matter inaccessible to logical analysis. Wittgenstein felt that even Russell did not understand The Tractatus. He then withdrew from philosophy.

From 1920 to 1926, Wittgenstein worked as a teacher in a rural elementary school, then as a gardener at a monastery, and as an architect: he was commissioned by his sister to design and build her a house in Vienna, proving himself a gifted architect. In the late 1920s, Wittgenstein returned to philosophy and moved to Cambridge. Despite his fame, Wittgenstein could not teach at Cambridge, for he did not have a doctorate, and Russell suggested that he submit The Tractatus as a dissertation. The work was examined in 1929 by Russell and the philosopher George Edward Moore. The dissertation defense was more like a conversation between old friends, at the end of which Wittgenstein patted the two experts on the shoulder and said: “Don’t worry, I know you’ll never understand this.”

In the examiner’s report, Moore wrote, “I believe this is a work of genius, but, even if I am wrong, this work is far above the standard required for a Ph.D. degree.” Wittgenstein was appointed a lecturer and became a Fellow of Trinity College. He lived in the UK from 1929, and from 1939 to 1947 he worked at Cambridge as Professor of Philosophy.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Wittgenstein defiantly declared himself a Jew. In 1935, after a long study of the Russian language, he visited the USSR, intending to stay there and do research, but soon returned to England. A Soviet Jewess, Sophia Yanovskaya, Ph.D., told Wittgenstein so convincingly about the dogmatic approach to philosophy in the USSR that he changed his mind about moving. During World War II, Wittgenstein interrupted his teaching to work as an orderly in a London hospital. He died in Cambridge on April 29, 1951.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.