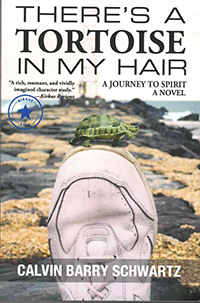

There’s a Tortoise in My Hair by Calvin Barry Schwartz; Earthood Media, LLC; (c) 2021; ISBN 9792218-295745; 325 pages; $18.99.

SAN DIEGO — The title of this book, referencing “tortoise” and “hair,” immediately brings to mind Aesop’s Fable about the race between the tortoise and the hare in which the slow and steady tortoise defeats the brilliantly fast but overly distracted hare.

SAN DIEGO — The title of this book, referencing “tortoise” and “hair,” immediately brings to mind Aesop’s Fable about the race between the tortoise and the hare in which the slow and steady tortoise defeats the brilliantly fast but overly distracted hare.

The protagonist in this story, Cameron Simmons, metamorphizes from a “hare” during his childhood and early-to-middle adulthood to a tortoise in his golden years, finding spiritual relevance in the number sequences 444 and 111. His parents are Jewish, and he is nominally a Jew, but one who evinces an extraordinary interest in Christmas, Jesus, and Christian saints on his spiritual journey. Simmons says Albert Einstein also is his spiritual guide, but the theorist of relativity has little relevance to the narrative.

Simmons invented biography includes graduation from Rutgers University in New Jersey, an unsatisfying career as a drug store pharmacist which eventually he quits to become an eyeglass salesman; drug use; an unsuccessful first marriage; a second marriage to an especially patient woman who puts up with his peccadillos; and a post-retirement career as a blogger, podcaster, journalist and author. Author Schwartz’s career, as outlined in the back of the book, is strikingly similar, but the book is presented as a work of fiction with the caveat that “any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead … is entirely coincidental.”

In early childhood, Simmons was slow to develop verbal skills, prompting his father to comment that the boy must have a tortoise in his hair. However, he grew to be 6’5″, was quite accomplished as an intra-collegiate basketball player, had a charming smile, and ladies (at least in his telling) pursued him. Having sex was his distraction; a virgin until his 20s, he made up for it with abandon in later life.

After his second marriage, startingly, as a salesman on the road, he wined, dined, flirted, and teased random women, but backed out when otherwise the relationships would have been sexually consummated. He believed that such behavior was being true to his marriage; he enjoyed the excitement of the successful pursuit without the guilt of extramarital sex. He lusted in his heart the way Jimmy Carter once confessed to Playboy magazine that he did. Unlike Carter, he acted on that lust, just not to completion. If his wife had found out, she’d have been justified in filing for divorce.

Then he became interested in life-after-death and encountered all kinds of “evidence” that the dead could communicate with the living. This became another obsession, not replacing sexual fantasy completely, but definitely crowding it for space in his brain. He continued to love his wife, take pride in his son, and in addition taught a course at Rutgers about finding a career.

This novel leaves us with no profound thoughts or revelations, yet the character Cameron Simmons is an interesting one, perhaps reminding us of people we knew or once were.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.