By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — Germany’s defeat in World War I and the fall of its monarchy led to the complete legal equalization of Jews with Germans. Jews achieved emancipation in a country that had been exsanguinated, humiliated by war, crushed by inept leadership, and robbed by the victorious allies. What the Jews failed to accomplish in peaceful and prosperous Kaiser’s Germany, they succeeded in a country that had suffered a terrible defeat and was devoured by hyperinflation.

Since November 1918, the struggle of German Jews for the reorganization of Germany began on an unprecedented scale. The newborn German republic became the arena for Jewish attempts to save the fatherland and to reorganize German society. The years 1918-1933 saw the flowering of scientific, cultural, and revolutionary activity among German Jews. Jewish socialists and intellectuals Rosa Luxemburg, Kurt Eisner, Ernst Toller, Gustav Landauer, Erich Mühsam, and Eugen Leviné became leaders of the revolution in Germany. For 15 years, Jews made attempts to reorganize Germany, to make it tolerant of Jews, not acceptable in terms of the racist ideology of German antisemitism. The dreams of the Jewish transformers were colored in the red of socialism.

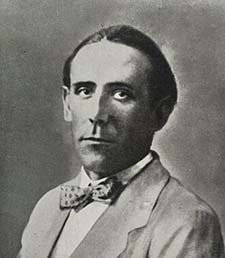

On July 18, 1891, Emil Julius Gumbel was born in Munich into the Jewish family of a private bank manager. In 1910 he graduated from gymnasium, studied economics and defended his doctoral thesis on “On the interpolation of the state of the population” (1914). In 1914 he volunteered for the front, but in the war he became a pacifist. In the spring of 1915, he resigned from military service and joined the pacifist Union for a New Fatherland, renamed in 1922 the German League for Human Rights. He worked for the Telefunken firm.

In 1917 he joined the National Social Democratic Party of Germany, and in 1920 he switched to the Social Democratic Party of Germany. However, he was a man of independent views, was a “one-man party,” valued democracy, rejected revolution, and in November 1918 spoke against the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” preaching the convocation of a national assembly.

In 1929, a German writer of Jewish origin, Lion Feuchtwanger, published the novel Success. The ninth chapter From the history of the city of Munich begins as follows: “In those years [after the end of World War I] one of the most favorite ways to refute the arguments of a political opponent was murder. In Germany, this means was resorted to mainly by the adherents of right-wing parties, who were not as skillful as the leaders of the Left in wielding spiritual weapons”.

In a small book Four Years of Political Murders (1922), Emil Julius Gumbel, who became professor of mathematics and statistics at the University of Heidelberg, gave the following data: after the end of World War I, 376 political murders were committed in Germany, among them 22 were committed by left-wing extremists, 354 by right-wing extremists. Postwar German democracy clearly sympathized with the right, its justice system punished the leftists harshly and treated the rightists leniently: the leftists received 248 years in prison, the rightists 90 years and 730 marks in fines, ten left-wing terrorists were executed, not a single right-wing terrorist among hundreds of murderers was executed.

Gumbel did not have time to include in the book the years of comfortable imprisonment awarded by German justice to Hitler for the Bavarian “beer” putsch of 1923. In 1921, a man of left-wing views, Justice Minister Matthias Erzberger, was assassinated by right-wing extremists. The Prussian Ministry of Justice concluded that “Gumbel’s data are true.” After the assassination of Walter Rathenau, the Jewish foreign minister, by right-wing extremists in 1922, he wrote: “The right-wing tends to hope that it can destroy the left-wing opposition by killing its leaders. […] The effectiveness of this technique is for the moment indisputable.”

Gumbel was an active pacifist. In 1924, speaking at a meeting of the German Peace Society, dedicated to the tenth anniversary of the outbreak of war, he said of the dead soldiers: “I do not want to say that they fell on the field of dishonor, but their deaths were truly terrible.” For these words he was dismissed from the university. But he was soon welcomed back under pressure from the Minister of Worship of Baden-Württemberg.

After the publication of his books Conspirators (1924) and Traitors on Trial (1929), a case of treason was brought against Gumbel, which was soon dropped. However, after his appointment as professor extraordinaire, a “Gumbel Riot” took place against the pacifist and Jewish Gumbel at Heidelberg University. Nazi students seized the building, demanding his dismissal. The university administration called the police.

Albert Einstein was one of the most active campaigners for Gumbel. At one of his rallies in 1930 he said: “The external reason for our meeting is the Gumbel case. This apostle of justice has written about unthinkable political crimes, has written with skill, passion, extraordinary courage and honesty worthy of emulation, and with his books has opened the eyes of the public. And this is the man that students and the vast majority of colleagues are trying with all their might to kick out of the university.”

On August 31, 1932, Gumbel gave an interview to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in which he described his situation and predicted the immediate future: “The Nazi students meant to be the dictators of the universities in Germany. They have strongly opposed me for years because I have shown how they have murdered innocent people. […] They hate me because I am a pacifist. […] The Nazis are simply the old forces which formed the Kaiser’s regime. […] They will continue to assassinate people, especially the Jews, because antisemitism is popular in Germany.” In 1932, Gumbel was barred from teaching. This was perhaps the first victory for the Nazis before they came to power. Gumbel publicly opposed the Nazi Party and, in 1932, he was one of the 33 prominent signers of the Urgent Call for Unity.

After the Nazis came to power, Gumbel’s name appeared on the list of authors whose books were to be burned and on the first list of persons deprived of German citizenship. By then he was already in France, where he wrote anti-Nazi publications and helped German immigrants to settle. In 1940, after the German takeover of France, Gumbel immigrated to the United States. After the war, he tried to reinstate himself at the University of Heidelberg, but his request was denied. Gumbel was granted American citizenship and was a professor at Columbia University from 1953. On September 10, 1966, he died in New York City.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.