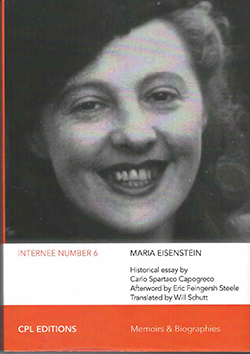

Internee Number 6 by Maria Eisenstein with an historical essay by Carlo Spartaco Capogreco and a family remembrance by Eric Feungersh Steele; New York: Centro Primo Levi; © 1944; ISBN 9781941-046340; 321 pages.

SAN DIEGO — The Centro Primo Levi in New York is dedicated to exploring the Italian Jewish experience, particularly that of its namesake Primo Levi, a chemist, Auschwitz survivor, novelist and essayist.

SAN DIEGO — The Centro Primo Levi in New York is dedicated to exploring the Italian Jewish experience, particularly that of its namesake Primo Levi, a chemist, Auschwitz survivor, novelist and essayist.

It recently republished in English Internee Number 6, the 1944 account by Maria Eisenstein of her incarceration in the Villa Sorge in Lanciano in the Abruzzo region of Italy during World War II. Her crime? Being a foreign Jew.

The Villa Sorge was a private residence into which 75 women were crowded, speaking a variety of languages, and not all of them Jews. A topic of speculation was who was a spy among their fellow internees, who might be providing sexual favors to their captors in return for preferences, how bad the food was, and how a Jewish internee like herself could reach an understanding with another internee who was a self-described Nazi. Throughout Eisenstein’s book was the constant worry that she and her fellow Jews would be turned over to Fascist Italy’s German Nazi allies.

While an internee, Eisenberg had certain privileges: She could walk outside the villa for an hour a day, even purchasing food and other necessities at a local market (which overcharged the prisoners). She could petition her captors if she felt she was being treated especially unfairly (beyond the fact of her unjustified imprisonment). She was free to read, gossip with the other women, and to otherwise peacefully endure her confinement. When ill, she could be well treated at a hospital.

Carlo Spartaco Capogreco, an historian, argues in a follow-up section of the book that the conditions of Italian confinement ought not be contrasted superciliously with the horrors of the death and work camps established by Nazi Germany. Such comparisons are invidious; what benefit is there in establishing a hierarchy of suffering? Must the Jews imprisoned in Italy feel guilty because they were not subjected to the same levels of cruelty as those in German-run concentration camps? Their lives were disrupted, their freedom was taken from them, and many were sickened, some fatally, in such confinement.

In the book, there is also a family remembrance by Eisenberg’s son, Eric Feingersh Steele. After the war, Eisenberg moved to Los Angeles, where she lived as a single mother of an only child. She was a non-conformist, who knew her own mind; a teacher and lecturer, who survived for 12 years following a cancer diagnosis.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.