By Alex Gordon

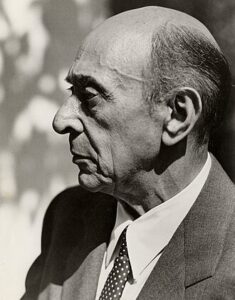

HAIFA, Israel — Arnold Schoenberg was born on September 13, 1874 in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt neighborhood (a former Jewish ghetto) to a Jewish family. His mother, a native of Prague, was a piano teacher and his father was a shopkeeper. At the age of six he entered elementary school; at the age of eight he began learning to play the violin. He composed his first works for two violins at the age of nine. At age 11, he was writing marches and polkas. Arnold’s father died when the boy was 15 years old. At 17, he dropped out of school and began working in a bank. In 1898, Schoenberg converted to Protestantism. Arnold did not study at a music academy, but only took counterpoint lessons from Alexander von Zemlinsky (in 1901 Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde).

From the age of 20, Schoenberg made a living orchestrating operettas, while also composing works in the style of late nineteenth-century German music. His best-known work is the string sextet Enlightened Night (1899). Schoenberg is recognized by composers Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. In the 1910s his music was popular in Berlin among expressionist writers.

World War I shook Schoenberg, a patriot of the German-speaking world, to the core. Alex Ross, music critic for The New Yorker, wrote: “Schoenberg fell into what he would later call ‘war psychosis’ – he compared the German army’s attack on decadent France to his own attack on decadent bourgeois values.” In an August 1914 letter to Alma Mahler, widow of Mahler, Schoenberg, in Ross’s words, “displayed a fierce militancy in his support for German arms while simultaneously condemning the music of Bizet, Stravinsky and Ravel.”

He wrote to her: “My friends know, I have often told them this: I could never find anything good in foreign music. It has always seemed to me exhausted, empty, disgustingly sweet, haggard and inept. Without exception. Now I know who the French, the English, the Russians, the Belgians, the Americans and the Serbs are: Montenegrins! That’s what the music told me a long time ago. I was surprised that not everyone felt the same way I did. That music had long ago been a declaration of war, an attack on Germany. But now comes the time to pay the bills! Now we will take all these mediocre kitsch creators into slavery again, and they will have to glorify the German spirit and pray to the German god.”

The defeat of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires in World War I, their collapse, the crisis and decline of the German world dear to him caused the composer’s “revanchist” reaction. His pride in German music manifested itself despite the outbreak of anti-Semitism in Germany, marked by the assassination of the Jewish Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau by right-wing extremists. Until 1925, Schoenberg lived primarily in Vienna. In 1925 he became professor of composition in Berlin at the Prussian Academy of Arts.

In articles, Schoenberg often referred to music as “divine predestination” and the ability to compose as “a gift from God”. In them Schoenberg often refers to himself as “the musical chosen one,” the successor of his “god-inspired” predecessors: Mahler, Wagner, Beethoven, Mozart and Bach. But he was banished from the German world, and in 1933, after the Nazis came to power, Schoenberg emigrated to the United States. On his way there, in 1933, he underwent a rite of conversion to Judaism in a synagogue in Paris.

In the summer of 1922, Schoenberg informed his student, the Austrian musicologist Joseph Rufer, of his discovery of the 12-tone method of composition. Schoenberg’s method of dodecaphony was revolutionary in music, and the composer often proudly noted that the new method of composition would “establish the supremacy of German music for several hundred years.” Schoenberg continued to be a German nationalist, even though he first experienced national discrimination as early as 1921, when the composer’s entire family was evicted from a hotel whose rules did not allow Jews in the rooms. Six years later, the composer wrote to the artist Vasily Kandinsky: “I was forced to realize and remember forever that I am not a German, not a European, I am a Jew.” Discrimination reached its climax on April 7, 1933 – from that day on the new Nazi Law on the Restoration of Officialdom Jews were forbidden to work at universities.

In a letter that Schoenberg wrote in 1933 to his pupil Anton von Webern, the composer spoke of the influence of antisemitic sentiment on his Jewish identity: “I have long ago decided to be a Jew. […] I have returned to the urban community and intend to take an active part in its life. […] I consider it much more important than my art and am determined to do nothing in the future, […] only work for the Jewish national cause.”

In the United States, he taught at UCLA. In 1938, he published a Zionist article, A Four-Paragraph Program for Jewry, in which he called for an independent Jewish state, and worked on an oratorio for chorus and orchestra, All Vows (based on the melody of the Kol Nidrei prayer). Schoenberg developed the theme of Jewishness in the unfinished oratorio Jacob’s Ladder (1922) and the oratorio Survivor from Warsaw (1947), which ends with the composer’s protest against the Holocaust by showing a picture of Jews walking to their doom and singing Shema Israel.

One of Schoenberg’s most significant achievements was his unfinished opera on the biblical story Moses and Aaron, begun in the early 1930s. The music of the opera is based on a single 12-voice series. Schoenberg died on July 13, 1951 in California and is buried in Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

Schoenberg saw tonal music as a false distortion of life and created with the method of dodecaphony. Protesting against traditional harmony, which expressed the serenity of life in an age of storms, he believed that “Music should not decorate but be true and only.” Theodor Adorno, composer, musicologist and philosopher of the Frankfurt School, who put forward a critical philosophy of society, extended it to music. He saw in Schoenberg’s dodecaphony a criticism of beautiful, tonal music that hides the ugly aspects of life. Adorno supported Schoenberg’s music as a protest against the serenity of art at a time of great upheaval in society. In the spirit of the Frankfurt School, Adorno considered Schoenberg’s work as critical music.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 11 books.