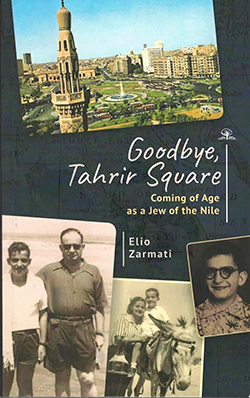

Goodbye, Tahrir Square: Coming of Age as a Jew of the Nile by Elio Zarmati; Newton, Massachusetts: Cherry Orchard Books, an imprint of Academic Studies Press; © 2024; ISBN 9798887-196664; 371 pages including photo section; various prices on Amazon.

SAN DIEGO – Elio Zarmati’s memoir is of a Jewish boy growing up in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. When Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956, which up to then was controlled by Britain and France, those two colonial powers plus Israel invaded Egypt. However, the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Nations successfully put pressure on them to desist, sparking adulation in Egypt for Nasser’s revolutionary government and enmity against France and England and intensified hatred toward Israel, then only eight years old.

SAN DIEGO – Elio Zarmati’s memoir is of a Jewish boy growing up in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. When Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956, which up to then was controlled by Britain and France, those two colonial powers plus Israel invaded Egypt. However, the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Nations successfully put pressure on them to desist, sparking adulation in Egypt for Nasser’s revolutionary government and enmity against France and England and intensified hatred toward Israel, then only eight years old.

The Mideast turmoil left Egypt’s Jews, some of whose families had been resident for centuries, in an unenviable situation. Thought to be sympathizers for Israel, Jewish families came under suspicion and repression, forcing many to leave. But some stayed for a variety of reasons, attachment to their Egyptian homeland being one, wanting to protect their investments another, and not applying in time for the required exit permit still another.

Elio’s bitterly divorced parents were among those who lingered notwithstanding the hostile political climate. His mother was a queen bee of a social circle that included prominent Muslims, Coptic Christians and Jews. His father, a merchant, delayed his emigration decision and subsequently was unable to secure an exit permit even after paying bribes.

With a no-holds-barred war in Gaza between Hamas and Israel fresh in contemporary readers’ memories, it may be a surprise that even after the Suez War, the Jews who remained in Egypt were able to go about their business relatively unmolested. Mother Zarmati still met at fancy restaurants with her social group; Father Zarmati still dated single women; and Elio, distrustful and resentful of authority, still was being suspended or expelled from schools for acting out.

Part of Elio’s problem was his feuding parents. He lived with his father six days a week and visited his mother in another neighborhood of Cairo one day a week. That day was filled with his mother’s complaints about his father, so angry that Elio felt distressed just listening to them. Although his father didn’t mention his mother quite so often, when her name came up in conversation, he seemed to greet the mention always with a sneer.

Elio was the subject of two homosexual assaults. One was a case of an older man rubbing his penis against the young boy’s thigh, then running away. Another was an older schoolboy sodomizing Elio. These crimes went unreported to authorities, but they may have been unspoken factors in Elio defying authority at school and being disrespectful.

Yet, Elio also avidly consumed world history, which his father made interesting by his knack for storytelling, and classic literature, which he found in plentiful bound books in his late grandfather’s personal library. He also from an early age took an interest in current events. He asked more questions than either of his parents could answer.

He had heterosexual experiences even before his bar mitzvah. The first came at the conclusion of a romance with a vacationing American girl several years older than he was. He had lied about his age. The second, accompanied by a friend, was at a bordello. The third was with an Arab woman, soon to be married.

Walking or bicycling, Elio habitually explored Cairo’s varied neighborhoods, lingering especially at Tahrir Square where national celebrations occurred, at the souks, and at the bookstores where he loved to linger.

Grown up Elio is nostalgic about Cairo’s historic spots and analytical about Egyptian national prejudices. To this reader, the memoir seems like an objective portrait of an Arab country from a Jewish perspective. It’s neither too bitter nor too saccharine.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.