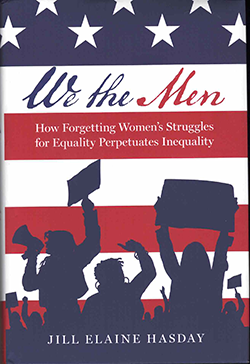

We The Men by Jill Elaine Hasday; New York: Oxford University Press; © 2025; ISBN 9780197-800805; 205 pages of text and 96 pages of appendices; $34.99.

SAN DIEGO – Author Jill Elaine Hasday analyzes court ruling upon court ruling to show that while Americans congratulate themselves about extending full equality to women, actually some laws continue to be oppressive.

SAN DIEGO – Author Jill Elaine Hasday analyzes court ruling upon court ruling to show that while Americans congratulate themselves about extending full equality to women, actually some laws continue to be oppressive.

The book title We the Men reflects her feeling that the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, in truth, should have not begun with the gender-inclusive words “We the People” because women were excluded from the process.

The book argues persuasively that Courts have alluded to gender equality in the United States – which is a myth – while frequently ruling in favor of continued inequality.

Legal scholars might write comprehensive reviews of Hasday’s research. For our purposes, let us examine the contrasting decisions of two Jewish justices of the U.S. Supreme Court: Felix Frankfurter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Their decisions represent both sides of women’s struggle for legal equality, Hasday reports.

Jewish attorney Anne Davidow brought to the court in 1948 a challenge to Michigan’s law prohibiting women from bartending in cities with more than 50,000 population. Justice Felix Frankfurter, appointed in 1939 to the Supreme Court by Franklin D. Roosevelt, decided against women and in favor of the Bartenders Union in the case named Goesaert v. Cleary.

Thirty years after the decision, Davidow said she had been heckled from the bench by Frankfurter, who informed her that “the days of chivalry aren’t over.” Attorneys for the Bartenders Union had argued that drinking men might put female bartenders at risk, so the restrictions were for women’s own good. However, women were permitted to work as cocktail waitresses serving men at their tables, which arguably put them in more danger than being stationed behind a bar.

In contrast, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, appointed in 1993 to the High Court by President Bill Clinton, struck a blow for gender equality. In 2017, she wrote the majority opinion in Sessions v Morales-Santana.

Luis Ramón Morales was the child of a mother of Dominican Republic citizenry and to a father of U.S. citizenry. The law required the father of a nonmarital child to have lived in the U.S. ten years prior to the child’s birth for that child to be considered a U.S. citizen. However, the law treated U.S. citizen mothers differently. They needed to be residents of the U.S. only one year prior to the baby’s birth.

In her opinion, written for the majority, Ginsburg described as an “obsolescing view” that “unwed fathers are invariably less qualified and entitled than mothers to take responsibility for nonmarital children.”

The high court ordered that residency requirements for parents, regardless of their gender, be the same length – either one year or ten years. The court chose the longer residency requirement.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.