By Jerry Klinger

PORTSMOUTH, Ohio — On August 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln responded to Horace Greeley, a noted abolitionist. The Civil War was not going particularly well for the Union. Lincoln was being pressed on the issue of Slavery and the Union cause.

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union, and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

Three weeks later, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia invaded the North. Lee was opposed by George McClellan. September 17, 1862, they clashed at Antietam Creek, Sharpsburg, Maryland. It was the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War; over 22,000 men were killed or wounded.

Lincoln used the Union victory to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. Church bells rang and newspapers printed banner headlines: if the rebellious South did not surrender, on January 1, 1863, the slaves would be free.

Only it was not entirely true.

Lincoln’s Proclamation only freed the slaves in those areas of the South still in rebellion. The Proclamation was an economic cudgel, a sanction, against the South. If the still-rebellious South surrendered, the Proclamation would be moot. Slaves in Union states such as Maryland and Delaware remained enslaved. Slaves in the formerly rebellious states remained slaves.

James M. Ashley was born in 1824 in Southern Ohio. He grew up in a Christian Fundamentalist Household. His father, an itinerant preacher, frequently took James along with him as he traveled from Ohio into Kentucky, a slave state. Young James saw and was horrified by the Black slaves he encountered. The terror of chattel slavery convinced James that slavery was fundamentally anti-Christian. Slavery was absolute evil.

Against his father’s wishes, James, though only 17, began smuggling escaping slaves from Kentucky to Ohio. In his twenties, he was part of the extremely dangerous Underground Railroad, actively freeing slaves. If caught, slaves would be returned to slavery. Those helping them would be killed.

When his role in the Underground Railroad became known, James Ashley and his wife fled Portsmouth for Toledo, Ohio. He became a founding member of the anti-slave Republican Party. Ashley was elected to Congress for five terms, 1859-1869. Ashley was more than a Republican; he was a Radical Republican. His agenda was to end the hated institution of Black chattel slavery forever. In Congress in 1862, he introduced legislation to end slavery in Washington, D.C. He pushed Lincoln to do more.

It became very clear to Ashley that the Constitution of the United States had a fundamental flaw. Slavery was legal. If the Civil War ended, and the formerly rebellious slave states were readmitted to the Union, they could legally reestablish Slavery. The Constitution needed to be amended, to be fixed.

Ashley became the driving force for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, legally ending slavery forever.

The 13th Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865. It forbade slavery. And it forbade every American from engaging in slavery, across the United States and in every territory under its control, except as a criminal punishment.

Lincoln might free the slaves with a Union victory. Ashley legally ended slavery forever.

Except he did not…

Slavery, including chattel slavery, not necessarily only Black slavery, remained legal in Indian territory, and later in Alaska, and Hawaii, after the 13th Amendment was ratified. Native Americans were deemed sovereign nations. They were not legally American citizens subject to American jurisdiction until 1924.

The battle over slavery would continue to be fought in the courts.

Sitka, Alaska, 1886, a horrifically mutilated Haida, Native American Alaskan, named Sah Quah, stood in a Federal Court petitioning the court to be declared free from enslavement by his owner, a Tlingit Native Alaskan. The court ruled that the American government had never recognized the Haida or the Tlingit as Sovereign Nations, but only permanent residents on American territory. Sah Quah was free because of the 13th Amendment. Slavery in Alaska, practiced for millennia by Native Americans, was illegal.

Over the years, Ashley’s 13th Amendment has been expanded to mean many things and cover many weaker, victimized people. Slavery by peonage, by sex trade, slavery by ethnicity, or religious belief, and more, is illegal.

As antisemitism increases, could the slavery of Jews be a future issue?

Impossible? It happened just 80 years ago. The most civilized and cultured nation in the world, Germany, practiced it.

A Holocaust survivor reflected to me when he first encountered anti-Black racism in Washington, D.C. He said, “If it were not for the Blacks, it would be the Jews in their place.”

Vigilance against hatred, ignorance, and bigotry must never become lax.

All people owe James M. Ashley recognition and gratitude.

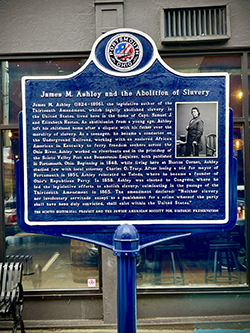

When the opportunity came to place the first-ever historical marker honoring Ashley, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, in partnership with the Scioto Historical Society, did so. April 7, 2025, on 2nd and Court Street, in Portsmouth, Ohio, the Ashley marker was sited.

The text reads:

“James M. Ashley and the Abolition of Slavery

James M. Ashley (1824–1896), the legislative author of the Thirteenth Amendment, which legally abolished Slavery in the United States, lived here in the home of Capt. Samuel J. and Elizabeth Huston. An abolitionist from a young age, Ashley left his childhood home after a dispute with his father over the morality of Slavery. As a teenager, he became a conductor on the Underground Railroad, working with an enslaved African American in Kentucky to ferry freedom seekers across the Ohio River. Ashley worked on riverboats and in the print shop of the Scioto Valley Post and Democratic Inquirer, both published in Portsmouth, Ohio. Beginning in 1848, while living here at Huston Corner, Ashley studied law with local attorney Charles O. Tracy. After losing a bid for mayor of Portsmouth in 1851, Ashley relocated to Toledo, where he became a founder of Ohio’s Republican Party. In 1859, Ashley was elected to Congress, where he led the legislative efforts to abolish Slavery, culminating in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. The amendment declared: “Neither Slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

*

Jerry Klinger is the President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.