By Cynthia Citron

HOLLYWOOD–Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman still stands as the monumental and definitive portrait of a man of the post-World War II generation, angst-ridden, driven, and ultimately crushed by the nightmarish underside of the American Dream.

In a comparably brilliant play, Edmund White brings that portrait up to date with a harrowing exposition of the destructive anger, frustration, and isolation of a militant, self-righteous sociopath.

The play is Terre Haute and the man is Timothy McVeigh (here called “Harrison”). Languishing on Death Row in the U.S. Federal Penitentiary at Terre Haute, Indiana, he is visited five days before his execution by a distinguished American writer, an ex-pat who observes his country with detachment and disdain from his home in Paris. (Virtually the only difference between this writer, here called “James”, and writer Gore Vidal is that Vidal made his home on Italy’s Amalfi coast.)

Terre Haute is White’s vision of “What if?” What if Gore Vidal had actually met Timothy McVeigh and had been able to question him about his motives for killing 168 people (including 19 children) and wounding another 500 in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995? In reality, as in the play, the two men had corresponded for several years and Vidal had written a series of magazine articles about McVeigh, but they never actually met. Apparently White used these exchanges as the basis for his play.

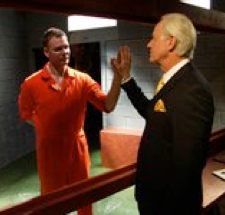

As White portrays them, James is a pompous, condescending, and self-absorbed “personage”—a man mightily impressed with himself and his accomplishments, while Harrison, self-taught and articulate, feels thoroughly justified in having acted against what he sees as a corrupt, covert, and tyrannical government. Two men who would seemingly have nothing in common, and both potentially unlikable. But thanks to impeccable casting and the sensitive direction of Kirsten Sanderson, the play is not only provocative and riveting, but also unexpectedly sympathetic to both characters.

As for the casting, who would think to cast Mike Farrell, Alan Alda’s funny, practical sidekick in M.A.S.H. as the acerbic, mannered writer and Jim Parrack, the sweet vampire-lover in True Blood as the remorseless mass-murderer? Brilliant on both counts. And as a particularly ironic plus, Parrack also has the advantage of being Timothy McVeigh’s haunting look-alike.

Harrison revels in the opportunity to explain his evolution from a soldier who aspired to become a Green Beret (he couldn’t pass the physical challenges) to a disciplined, methodical, militant murderer. He claims that he hadn’t known that there was a children’s day care center in the Murrah Building, but he dismisses the children’s deaths as “collateral damage” and notes that their presence “wouldn’t have stopped me even if I had known.”

James, whose understanding and sympathy become steadily more engaged in Harrison’s explanations and rationale for the bombing—he claims it was planned as retaliation for the FBI’s unwarranted killings of the family at Ruby Ridge and the members of the Branch Davidian cult at Waco—is also being influenced by his homoerotic attraction to the younger man. (James confesses that he is bisexual, even though Vidal consistently waltzed around the issue of his homosexuality.)

“I can’t make you sympathetic,” James tells Harrison, “but I want to make you credible.” Gradually, as they discuss their sexual fantasies and unfulfilled dreams, the two men appear more human and more alike, each revealing his own desperate alienation and his loneliness. As the aging James acknowledges at one point, “We’re both on Death Row.”

Terre Haute will continue at the Blank Theatre, 6500 Santa Monica Blvd. in Hollywood Thursdays through Saturdays at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 2 through November 14th. Call (323) 661-9827 for tickets. This one is a MUST SEE!

*

Citron is Los Angeles bureau chief for San Diego Jewish World