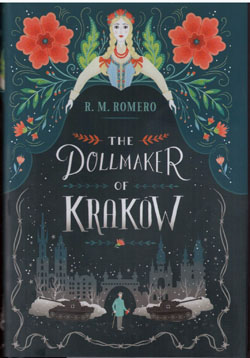

The Dollmaker of Krakow by R.M. Romero; Delacorte Press, 2017, ISBN 97815247-15403; 316 pages plus notes; $16.99.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — R.M. Romero has written a fairy tale that couldn’t possibly have a happy ending.

SAN DIEGO — R.M. Romero has written a fairy tale that couldn’t possibly have a happy ending.

Written for students in the middle school grades, The Dollmaker of Krakow is set in Poland during the Holocaust. From the troubled “Land of the Dolls,” the soul of a wise and perceptive doll named Karolina was blown by a gentle wind to the shop in Krakow of a dollmaker. Once she animated a doll’s body, Karolina could talk, emote, empathize—in fact she was human in almost every way, except for the fact that she was tiny and made of wood.

On arrival in Krakow, she thought she had escaped her troubled land where rats had overthrown the rightful king and queen and treated all the dolls like slaves. However, the human world soon became more and more parallel after the Germans invaded Poland

The Dollmaker, Cyril Brzezick, was a kindly but lonely man, who was imbued with magical powers. He was enchanted by Karolina and treated her like a daughter. One day, a Jewish girl named Rena visited the shop, with her father Jozef, a symphony violinist. Cyril, who was a Christian of German descent, found in Jozef a friend with a soul as sensitive as his. Karolina and Rena, meanwhile, became the best of friends.

Karolina was not the only special doll carried by the breeze from the Land of the Dolls. Fritz was another. He ended up with Erich Brandt, who became an officer with the Nazi SS, which oversaw the humiliation, imprisonment, and murder of Jews.

Brandt recognized that Karolina was alive like his doll, Fritz, had been before Brandt had tossed him into a fire. As Brzezick was of partial German descent, Brandt thought they might be friends. However, their values were very different, and the course of their lives diverged widely after the family of Rena and Jozef, along with the other Jews of Krakow, were penned up in a ghetto. The Dollmaker wanted to use his powers for good; Brandt, who was morally weak, believed all the lies told to him by his Nazi superiors.

Eventually, Brzezick, at great risk to his life, with Karolina’s help, devised a plan to try to extract Rena and other Jewish children from the ghetto and send them to safety under the protection of a kindly Catholic priest.

I’ll not spoil the rest of the story with other details.

I found myself wondering whether the story about the suffering of Jozef and Rena, which closely follows the historic pattern of the Holocaust, will be understood by students as a depiction of something that really happened, whereas the war between the rats and the dolls is strictly from Ms. Romero’s imagination.

Notwithstanding this doubt, I’m happy to recommend this book as important reading for youngsters, provided their teachers, parents, or guardians read it first, so they will be prepared to discuss it and elucidate upon its themes.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com