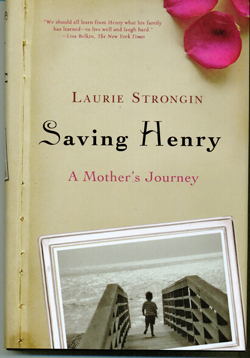

Saving Henry: A Mother’s Journey by Laurie Strongin, Hyperion, 2010, 271 pages including epilogue, $22.99.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—When Laurie Strongin comes to speak at 4 p.m., Tuesday, Nov. 9, at the Lawrence Family JCC, many in the San Diego Jewish Book Fair audience will attend not only to meet an author, but to meet a pioneer in the field of utilizing stem cells to provide cures for otherwise fatal diseases.

No, Strongin is not a doctor; the matter is far more personal to her than that. She is a mother of two children who were born healthy, and one child who was born with Fanconi anemia, a disease that doctors told her was almost always fatal. Everything humanly possible—everything—that could be done to try to save Henry, Laurie Strongin did –but in the end, the doctors were right, Fanconi anemia resulted in her child’s death at age 7.

One knows, at the very start of such a book, that it will be heartbreaking to read, and yet something makes a reader want to keep turning the pages to better understand the resilience of the human spirit – not only as shown by Henry, who fought his disease with an upthrust toy sword, a smile, and a cry of ‘bring it on’ whenever he had to undergo another medical procedure – but also by his mother Laurie, who medicated, stressed and fatigued herself day after day, month after month, in an effort to produce a baby whose stem cells could be transplanted from the umbilical cord into Henry.

One knows, at the very start of such a book, that it will be heartbreaking to read, and yet something makes a reader want to keep turning the pages to better understand the resilience of the human spirit – not only as shown by Henry, who fought his disease with an upthrust toy sword, a smile, and a cry of ‘bring it on’ whenever he had to undergo another medical procedure – but also by his mother Laurie, who medicated, stressed and fatigued herself day after day, month after month, in an effort to produce a baby whose stem cells could be transplanted from the umbilical cord into Henry.

For ideologues in the debate over stem cells—especially those who would sneer about ‘designer babies’ – Laurie Strongin would become a lady in a bulls-eye, someone willing to leave some potential lives unborn in a laboratory petri dish in her determined, relentless search for the proper genetic combination of her egg and her husband’s sperm to be implanted in her womb. She and her husband tried nine times to produce just the right egg and sperm combination to help Henry and simultaneously to give birth to a healthy child.

Readers, however, get a different picture of Strongin than the ideologues do. Once a carefree college girl, who encouraged her friends to go streaking naked in public just for the fun of it, her life was remolded by her son’s disease. Nearly everything she and her husband, Allen Goldberg, did after they received their baby’s death verdict was based on trying to save him. They took off long periods from work to travel to far-off hospitals, they followed the medical regimen for Laurie to produce not one but 20 eggs in a month, they raised money for research, and, most endearingly, they gave every single waking hour to seeing Henry not just as a patient, but as a joyful, loving, bright, little boy, who might, just might, somehow beat the odds.

As Henry’s plight became known throughout the country, he received many invitations. He met Bill Clinton at the White House, and talked baseball with Cal Ripkin. He got to ride on ferris wheels, go to Disney World, meet “Batman,” his favorite superhero, and do many things in his short seven years that other people could never experience in ten times as many years. And, Henry’s little brother Jack, didn’t lack for attention either – the two were best friends—and shared these adventures. One can’t help admire such devoted parents, who, though assailed by doubts and depression, shared Henry’s can-do spirit. If only all parents could so love their children with all their soul, with all their mind, and with all their hearts!

Strongin emerged from the experience with great compassion for other families with terminally ill children, and as a strong believer in the propriety and necessity for stem cell search to provide future cures. She is a woman for and of our times.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World