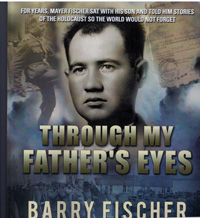

Through My Father’s Eyes by Barry Fischer; Fischer Family Press; © 2014; ISBN 9780991-073313; 211 pages; $19.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –This memoir is a good introduction to the Holocaust for middle school students and older. It is written in a clear, conversational style, the author remembering how his father, Mayer Fischer, described what happened to him during the Shoah.

SAN DIEGO –This memoir is a good introduction to the Holocaust for middle school students and older. It is written in a clear, conversational style, the author remembering how his father, Mayer Fischer, described what happened to him during the Shoah.

Mayer was different from many Holocaust survivors in that he didn’t keep his experiences bottled up, but instead began talking about them freely with his son, Barry, the author, while Barry was still of elementary school age. Mayer didn’t want the world to forget, and in retelling the story in his father’s words, Barry Fischer has honored his promise to always remember.

Interestingly, the author’s parents adopted different survival strategies during the Holocaust. The father, who had been interned at Melk, Mauthausen, and Ebensee prior to liberation, often took risks, figuring the Nazis would eventually kill him anyway. He credits-risk taking for his survival.

Blima, the author’s mother, was sent to the Gellenau and Langenbielau works camps in Austria. Her strategy was to follow the roles and to make herself inconspicuous. She spent her war years doing slave labor at a clothing factory. She knew if she ever got sick, she would be sent away to a death camp.

The difference in their approaches continued through the post-war years. While Mayer spoke frequently and publicly about his Holocaust experiences, for the most part Blima kept hers to herself.

There is one particularly poignant passage in the book, in which Barry related the circumstances leading to the death of Mayer’s father, Baruch, at Melk. While on a work detail, another prisoner accidentally hit Baruch’s leg with a shovel, incapacitating him. He asked to be taken to the infirmary. Hearing of this, Mayer rushed to the infirmary to get his father out of there. But he arrived too late. A “doctor” had already injected him with gasoline, purposely murdering the injured patient. Later, Mayer placed his father’s body in a wheelbarrow and took him directly to the crematorium. Emotionlessly, he told a guard that he had found the body on the grounds and decided to bring him there, not divulging that the man was his father. Pleased, the guard gave Mayer a cup of soup for his good deed.

One senses that of all the stories told to him by Mayer, Barry, who today practices family law in Beverly Hills, California, was perhaps the most haunted by this one.

Family photos and historic photos obtained through the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. amply illustrate this book, helping young readers to visualize the places where the atrocities occurred, and to experience the humanity of the victims.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com