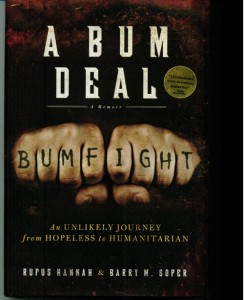

A Bum Deal: An Unlikely Journey from Hopeless to Humanitarian, by Rufus Hannah & Barry Soper, Source Books, ISBN -13: 97801-4022-4471-1; 2010, 238 pages, $24.99.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – For people in this city, one of the most startling things about this book is that its events occurred, in great measure, in the back of a small shopping center near the city line dividing eastern San Diego from suburban La Mesa. Although we perhaps have become inured to reading such accounts in newspapers, or seeing 10-second spots about them on the nightly news, we don’t expect them to take place where we buy our groceries or have our lunches in chain coffee shops.

But that’s an important point about homelessness, isn’t it? It’s not simply a phenomenon for the streets of downtowns. It’s not only a national disgrace that we can forget about once we commute home to suburbia. Homelessness is everywhere, as homeless people, too, head for the suburbs to seek their own version of peace and quiet or less competition for a safe place to sleep.

The co-authors of this book, Rufus Hannah and Barry Soper, are a study in contrast. Hannah was a homeless man from the rural South, who slept off his nightly drinking binges behind a suburban Vons Market. Barry Soper was and is a well-off, urban businessman who earns his money from real estate investments and his kovod from charitable works, including service on the board of an educational and treatment center for at-risk children in Murietta, California. Hannah is Christian, Soper is Jewish.

The co-authors of this book, Rufus Hannah and Barry Soper, are a study in contrast. Hannah was a homeless man from the rural South, who slept off his nightly drinking binges behind a suburban Vons Market. Barry Soper was and is a well-off, urban businessman who earns his money from real estate investments and his kovod from charitable works, including service on the board of an educational and treatment center for at-risk children in Murietta, California. Hannah is Christian, Soper is Jewish.

Their meeting was far from instant friendship. Soper was at an apartment complex he owned when he spotted Hannah and a fellow alcoholic, Donnie Brennan, diving through a dumpster looking for food and recyclables to finance their next beer binge. He yelled at them, threatened to call the police, and chased them off – only to be admonished by a local nonagenarian, Orlando Hawkins, for not offering them a job, instead of humiliating them. Abashed, Soper did just that—gave handyman jobs to Hannah and Brennan, paying them minimum wage provided that they showed up at work on time, sober enough to work.

Brennan, who liked Soper, and Hannah, who didn’t, accepted the jobs and its conditions, and thereby earned the money that they wasted in the evenings getting themselves drunk and stupid, while continuing to sleep outdoors behind a Vons Market.

But what seemed an easier route to beer money—though in the long run, it was far, far harder—presented itself in the form of teenage boys—high school students—with a penchant for making documentaries with their video cameras. But these teenagers weren’t content to go out and find the news; they created the news, by plying Hannah and Brennan with alcohol and the promising them even more money if they would participate in “stunts” – such as Hannah sitting drunk in a shopping cart and rolling down hill into a concrete abutment, Hannah falling down and hurting himself in various contrived situations, Brennan being sexually enticed by a porn movie actress, and Brennan and Hannah fist-fighting each other, with Brennan being knocked unconscious in the process.

It was, of course, a form of exploitation of the rawest sort, with the youthful entrepreneurs posting the videos on a pay-for-view internet site and raking in profits for what became known as “Bumfight” videos. The shots of poor, inebriated Brennan and Hannah humiliating themselves to earn their beers appealed to a sadistic audience. In their addled state, the two alcoholics thought of themselves as movie stars.

In the process Hannah and Brennan could have been killed, but after the teenagers transported them to a Las Vegas motel room, where they were dependent for beer and money on the film makers whose tastes were running to increasing violence, they telephoned Soper and asked to be rescued. Soper drove from San Diego to Las Vegas and gave them funds to get back to La Mesa.

Eventually, the exploitation came to the attention of law enforcement representatives who prosecuted the youngsters unsuccessfully. A civil suit followed and that was more successful, earning both Hannah and Brennan a settlement. Whereas Hannah controls his share of the settlement, a conservator had to be appointed for Brennan.

In the interim, Hannah had taken a good, hard look at himself and went through a painful rehabilitation process, with the encouragement of Soper. He survived the DT’s, regained his self-respect, and eventually became a nationally recognized speaker about homelessness. Today, Hannah works for Soper as an assistant manager at an apartment house complex. He is a changed man, who has reconnected with the children of three marriages he had abandoned during his early drinking days.

The central portion of the book concens the “bum fights,” because in their outrageous exploitation of homeless people, they attracted the attention of the national media. shortly before he died, Ed Bradley of television’s “60 Minutes” encouraged Soper to write a book about his experiences. Soper did so, but in the voice of his collaborator, Hannah, who eventually had become his friend and trusted employee. Not so Brennan, however, who despite his genial personality continued his homeless, alcoholic life.

One of the places described in some detail in the book is the Veterans Village in San Diego, a former motel along Pacific Coast Highway where ex-military men receive counseling and medical attention after they get themselves sober. Another program the book discusses is the annual Stand Down in the Balboa Park area where, over a long weekend, homeless veterans can find shelter in tents surrounded by showers, temporary medical offices, counselors, and other services. “Stand down” was a term used to describe the respite American soldiers in Vietnam got when they were withdrawn temporarily from the battlefield for some “rest and relaxation.” In using the term in the context of homelessness, Stand Down’s organizers acknowledged homelessness for the stressful battle that it is.

Both programs in San Diego are important and helpful, but I’ve long wondered why cities across America can’t take a page from Israel’s book, and used mobile homes – what Israelis call “caravans” – to create instant housing for the homeless. The Israelis utilized these caravans as temporary shelters in the process of absorbing millions of immigrants from war-torn Europe, North Africa, the former Soviet Union, Ethiopia, and other countries.

In many cases, caravans consisted of a bedroom on either side of the temporary structure, and a common living room, kitchen and bathroom in the middle of it. Thus two families could enjoy semi-privacy, and have a place to lock away their possessions while they attended language classes, orientation classes, and went on field trips to learn about their new country.

Similarly, one would think, such temporary structures could be erected in villages, and, similar to what happens during Stand Down, be surrounded with other structures containing social workers, medical and dental volunteers, job training courses, psychological counseling and the like – all with the intent to help the homeless to get back on their feet, begin the road to recovery from their addictions, and to once again live with dignity.

I am of the belief that every one of us, as a human right, deserves shelter. No society should force people down on their luck to sleep in the cold, or in the rain, or to go without proper sanitary facilities. We must recognize that passing ordinances that force the homeless to go from here to there, to move along and to get out of sight, neither helps them nor us. If Israel has the will to absorb millions of people coming from other countries and speaking other languages, cannot we Americans extend our hands and commitment to proportionately far fewer people by building temporary villages to serve them?

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World

I invite you to read about the San Diego Homeless situation on our website, NZ9F.com, and in the San Diego Homeless News, NZ9F.com/SDHN. Thank you for your book, as any attention to our problem helps. I contend that the Homeless Intellectuals Program (HIP) in San Diego is the only one which accurately understands the problem entirely, because while you do not need to BE homeless to understand same, it certainly helps. We currently have an off-and-on call for a boycott of Google, for marginalizing any web-links to our site, and have called for the resignation of San Diego Police Chief Lansdowne. We have also called for a tax on San Diego Padres baseball tickets, as their stadium and condo projects caused at least 2,000 of the County´s 200,000 (yes, that many!) homeless.