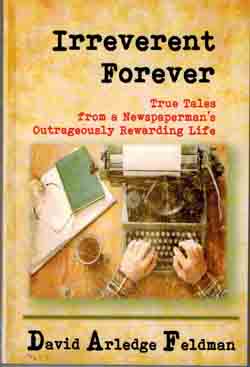

Irreverent Forever: True Tales From a Newspaperman’s Outrageously Rewarding Life by David Arledge Feldman; © 2018, Gray Castle Publishing, ISBN 9781987-713190; 226 pages plus appendix and acknowledgments.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Journalist David Arledge Feldman inherited his father’s sense of humor, but not his Jewish religion. For most of his life, Feldman followed his mother into a relaxed form of Christianity. Now he describes himself as agnostic.

SAN DIEGO – Journalist David Arledge Feldman inherited his father’s sense of humor, but not his Jewish religion. For most of his life, Feldman followed his mother into a relaxed form of Christianity. Now he describes himself as agnostic.

An immigrant from the Ukraine, David’s father Irving Feldman looked like Al Capone, especially when he wore his fedora. Otherwise, they were nothing alike. When a rabbi delivered Irving’s eulogy, he said: “Irving Feldman started out to be the world’s first honest lawyer. Then he switched to being the world’s first honest used-car dealer.” That may have been nice for Irving’s family to hear, but I wonder how many lawyers or used car dealers remained members of that rabbi’s congregation.

Dave Feldman had a long newspaper career which began in Arizona, migrated to Europe with the Stars and Stripes, and concluded as a copy editor with the San Diego Union-Tribune. He also was a longtime adjunct journalism professor at San Diego State University, and today not only has written his memoir, but copy edits the works of many other authors. He offers anecdotes from all those jobs, as well as from wide-ranging travel and endearing experiences with his wife, Betty, and two children, Greg and Tracy, whom sadly he outlived.

There are 67 chapters in this book, which means their average length is about 3 1/3 pages – most approximately the length of a newspaper column. I enjoyed reading the entire book, but owing to my role as editor of San Diego Jewish World, I found myself paying closer attention to those anecdotes dealing with Irving’s and my fellow Jews.

Jan Peerce and Herman Wouk, for example.

While working for the student newspaper at the University of Arizona, Feldman drew the assignment of interviewing opera singer Peerce. As Feldman didn’t know an aria from an aerator, this might have been a disaster, but for Peerce taking pity on the neophyte. Why did he sing the beloved “Pagliacci” late in the program, rather than at the beginning? “I could knock ‘em on their ass if I sang it first, but you have to work up to these things with the older songs first.” Older songs? “Pagliacci” premiered in 1892. Mozart was composing operas in the 1760s.

Feldman interviewed Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Wouk for the Tucson Daily Citizen. Wouk already had written The Caine Mutiny and Marjorie Morningstar. Other books like Winds of War and War and Remembrance were in the future. According to Feldman, Wouk was “disappointed that he wrote thousands and thousands of words too many for Marjorie Morningstar, which was about to be published, and he had to cut them.” The lesson may well have stayed with Feldman, who advised readers (in the book’s appendix) that a copy editor must be a “condenser.”

A Feldman maxim: “As a condenser, you’re taking out superfluous words. You’re tightening the writing. The best two words on editing I ever learned were ‘word trim.’”

While based in Germany during his Stars and Stripes days, Feldman avoided coming face to face with that country’s recent Nazi history. He wrote: “My Dad was Jewish. I admit that I never had the courage to visit Dachau, Buchenwald or any of the other death camps. The atrocities of World War II were never mentioned by the locals in our 13 years in Germany.”

In a reflection later in the book, he once again wrote, “My dad was Jewish” then went on to say: “But my mom wasn’t, so the Jewishness, which traditionally comes down from the mother, dad did not pass on to me. Except for my use of a few Yiddish words, I guess I’m not Jewish. (I had a Jewish name, and the rough boys who lived in the next block called us kikes. I didn’t know what it meant, but my mom did. She was not pleased.)

Feldman was a spectator at the 1972 Munich Olympics, returning to his job before the infamous murder of Israeli athletes by Palestinian terrorists. At work, he was called upon to combine reports from various wire services about the murders into a single story. “I did it, and I did it well for three days in a row,” he recalled. On a personal level, he was horrified. “At first I couldn’t believe it. Then I felt outraged. How could anyone do this?” Professionally, writing such an important story under deadline pressure was a growing experience. It proved to him that he was “a real newspaperman, not just a headline writer.”

Not that writing headlines is all that bad. The task gives copy editors an opportunity to be as witty as the headline count permits. One of Feldman’s colleagues, Johnny Neumyer, cleverly lined up a photograph. “He found a family named Montgomery that had a ward, a daughter. He had our photographer pose the daughter at a spit, with a deer being roasted, so he could write this headline above the photo: Montgomery Ward Sears Roebuck.”

Newspaper humor. I love it.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

The Author forgot to mention me in his wonderful book.I was in the US Army at the same time he lived in Darmstadt Germany.I spent some happy days in his home along with Betty (my Aunt)and Greg and Tracy (my Cousins). It was a very interesting time.