By Oliver B. Pollak

COLOGNE, Germany — In 1933 Cologne counted 20,000 Jews. In 1989 it had 1,358 Jews. Today the city of over a million, with the influx of Jews from the Former Soviet Union, has about 4,600 Jews.

The Holocaust produced catastrophic trauma. Post-war Germany maintains a leading position in rescuing people from persecution in their homelands, many from majority Moslem countries. Chancellor Angela Merkel has taken much heat for proposing an enlightened inclusive immigration policy in Germany and the European Community. Pardon the unabashed naiveté, part of this story stems from the concept of doing better, tikkun olam, repairing the world, disarmed intervention, based on a history of earlier misdeeds. Germans are owning their history. The following observations are based on two days of a family roots trip to Cologne in late May.

We stayed at the Pullman Hotel facing Erich-Klibansky-Platz. The Klibansky it is named for was the son of a rabbi, who opened a school in Cologne in 1929. After 1933 he prepared students to learn English to assist their removal to England. He was murdered in 1942.

A billboard across the street promoted Polish artist Jankel Adler, who for a while lived in Cologne, and a Marc Chagall exhibition at the Von der Heydt Museum Wupertal. Chagall also hangs in Cologne’s Ludwig Museum. Both were considered by the Nazis as producers of “degenerate” art. According to Wikipedia, Adler died in 1949 at the age of 53 years. None of his nine siblings survived the Holocaust.

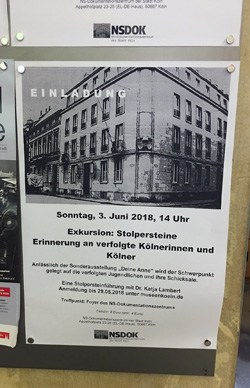

I saw several posters for an Anne Frank exhibit. Two blocks from our hotel was the N[ational] S[ocialism] Documentation Center. From 1935 to 1945 the building with four-floors and a basement was a Gestapo headquarters, ironically re-purposed into a Holocaust Memorial. The Anne Frank traveling exhibition is housed in the main floor gallery for three months. The exhibit text and most of the books in the bookstore are in German; this exhibit and the bookstore are designed with Germans in mind. The Nazi bureaucracy deeds exhibited on the second floor visibly sickened some of my family members.

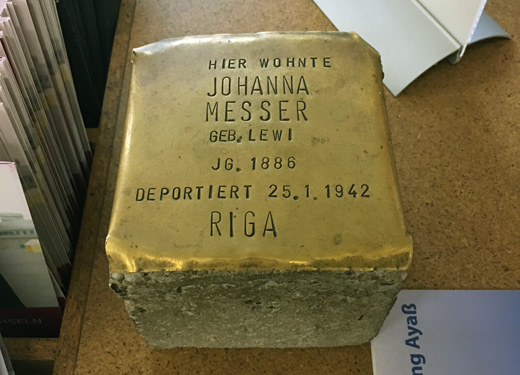

At the railway station next to the Cologne Cathedral, tucked into the side of the large plaza, singular railroad tie stuck out. On the tie were four bright brassy Stumbling Stones (Stolpersteines) to mark where Jews were transported to Konzentration camps. These commemoration stones started with Gunter Demnig in 1996 in Cologne. Cobble stones covered with a brass plaque are familiar sidewalk installations, a symbolic public apology. By the end of 2016 there were over 50,000 stones all over Europe. In our travels we saw many stolpersteines. This international human rights initiative and criticism of the Nazi legacy have not been universally welcomed in Germany. The bookstore has a stone from Riga, I did not ask if it was for sale, though the docent said some stones are being dug up by new Nazis.

Cologne is famous for its Kolsch beer served in a small glass with the waiter maintaining the tab with tick marks on the coaster. What a surprise to see Einstein promoting Kolsch beer.

In the square in front of the Cologne Cathedral three human rights advocates chained themselves to a fence under the banner “Sklavenmarkt” to protest human trafficking. Gemeinsam [Together] fur Afrika sponsored the protest.

A work by Serge Poliakoff (1906-1969) hanging in the Kunsthaus Binhold, established in 1938, would have been degenerate art if displayed in 1938. Walking back to the hotel after sunset another gallery window displayed the iconic art of Robert Indiana who had died a couple of days earlier (1928- May 19, 2010). Cologne appears to be a cosmopolitan city in the healthiest sense of the word, appreciating culture, reconciling history, empathy, and advocacy.

.

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, is a freelance writer now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com