By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – If you were a reader of Harper’s Bazaar or Vogue, especially during the 20th century, you might have become very familiar with the fashion photography of Irving Penn, who was born to a Jewish father and Christian mother in 1917. He took up a camera in the 1930’s and kept working at his photographic art almost to his death in 2009 at the age of 92.

The Smithsonian American Museum of Art assembled a retrospective of his photography in 2017 in celebration of the 100th anniversary of his birth. Now that exhibit, curated by Merry Foresta, is on tour, with San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Arts (MOPA) to be its only West Coast venue. With approximately 150 photographs mounted in chronological order, the exhibit covers some seven decades of Penn’s work, starting with his earliest photography in the 1930s to the highly stylized photography of his later years. It will officially open on Saturday and will remain on display through Feb. 17, 2019.

This, by no means, is simply photography featuring beautiful and incredibly thin women modeling some eye-catching fashions, although there is some of that, to be sure. Rather the exhibit is an exploration of Penn’s growth as a photographer, not only in the commercial realm, but also in the work that he did for his own pleasure and curiosity.

Other Jewish publications have noted that Penn was “elusive” in his Judaism, perhaps because he grew up in the highly assimilated Philadelphia home of his father, who was a watch maker as well as an amateur artist. His younger brother, the film maker Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde; Little Big Man; The Miracle Worker) went to live with their mother in New York after their parents’ divorce.

Although nothing in his work or at this exhibit is overtly Jewish, Irving Penn was influenced by and in turn was an influence upon other Jewish photographers. His mentor was Alexey Brodovitch, who was among the refugees from Europe who had been a member of Parisian café society, and helped to redesign America’s fashion magazines, most notably Harper’s Bazaar. Later in Penn’s career, photographer Richard Avedon was his “shadow,” according to Foresta, and all three of these men were influences on the work of Annie Leibovitz.

Those familiar with the Jewish wedding ceremony, when amid the joyousness of the nuptials, the groom stamps on a glass, causing it to shatter, may find an analogy to some of Penn’s photographs. Jewish tradition tells us that even when we are happy, we must also be cognizant of the sadness in life, as we are when by shattering the glass, we recall the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E.

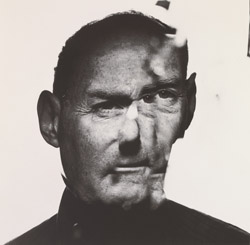

In some of Penn’s photographs, he inserts what he described as “poison in the picture” juxtaposing life and death, beauty and ugliness, youth and old age. For example, Foresta commented during a telephone interview from Washington D.C., there is a still life in the exhibit, in which there is a “table that was beautiful, with a ham, a bag of grain, a pitcher of cream, Limoges china, linen on the table, but if you look really closely on the bag of grain, there is a bug. He reminds us that we can’t take things for granted. There will always be the bug. There will always be the aged artist after the young artist. For me, one of the most poignant images [in the exhibit] is the fractured image of him.”

In another image, you don’t have to look very hard to find the bug. On a beautiful pair of lips crawls an insect!

During the last two years of World War II, Penn served as a photographer in Europe for the American Red Cross. He photographed American soldiers, as well as destroyed buildings, and refugees. He did not travel to the concentration camps, and none of his images evoked the Holocaust, although Foresta says Penn was very much aware of the genocide and of why it was necessary for America to go to war. ”He felt that World War II was about the preservation of culture, and indeed the preservation of beauty in all its forms. He talked about this throughout his life.”

On Tuesday, Oct. 2, members of the media were escorted through the exhibit by Deborah Klochko, MOPA’s executive director and chief curator, and by Joaquin Ortiz, the museum’s director of innovation. Klochko noted that Penn had not originally intended to be a photographer; instead he studied drawing, painting, and industrial design from 1934 through 1938 at the Pennsylvania School and Museum of Industrial Art. Following graduation, he followed Brodovitch from that school to Harper’s Bazaar, and it was only then that he purchased his first camera. Ortiz told us that the first part of the exhibit shows Penn’s “street photography,” perhaps influenced by both Walker Evans, whose photographs documented the American Depression, and Mexican photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo, “who was capturing similar things, but was trying to bring out art from everyday lives.”

According to Ortiz, Penn traveled by train through the American South and West, and “would hop off, and near the train station photograph all these things. … You will notice in these early pieces there is not that distinct Penn style. These are his early experiments. He was developing and growing as a photographer.” Some of the set ups, or compositions, drew upon painters he admired. The Dutch masters, and more modern painters like Modigliani and Picasso were reflected in his photographs.

Next, in the tour we came to a selection of photographs taken for fashion magazines, not only of female models but also portraits of up and coming men and women in the arts. In this series, he put his subjects into a bare corner of a room, and photographed them without any props. “Dancers… were among the earliest he brought into this project,” Ortiz said. “A dancer is familiar with empty spaces, using their bodies to fill in that open space…. Then he started photographing other figures.”

One of them was the artist Salvador Dali, to whom he had been introduced by Brodovitch. Rather than simply standing in the corner, Dali extended his arms and legs, so that his body filled up most of the frame of the photograph. “Dali wanted to be fully in that image,” Ortiz commented.

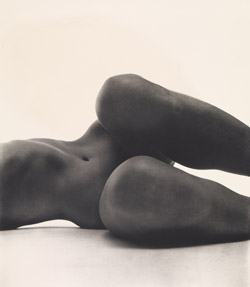

As Dali physically expanded his image, so too did Penn constantly try to expand the intellectual parameters of his work. The exhibit illustrates how important a role was played by juxtaposition, or what Klochko described as Penn’s penchant for “yin and yang.” Yes, the models he photographed for Vogue, where he spent the majority of his career, were perplexingly slender, but for his own private work, Penn liked to photograph “voluptuous women,” dare we call them zaftig?

As a fashion photographer, Penn was sent all over the world, but after photographing the haute couture, on his own time, he would take photographs of the common people. We see this in a section of the exhibit about his work in Peru. He returned to this practice, in even more sophisticated fashion, on assignment in Paris. Top models would come to his studio to be photographed, and later, in the same space, with the same kind of lighting, workmen posed for him with the tools of their trade. “He didn’t want to look at just one side of the world; he was always bringing those ideas together and pushing himself.”

Penn also photographed nudes, exploring the “landscape of the body,” Ortiz told us. “This was very forward thinking at the time. He made these images in 1949 and 1950.” Klochko added, “It was 30 year later before they were exhibited.” What was unusual about the photographs was that many of them were not full figure, but rather were examinations of the public regions of the body. His models contorted themselves, and one photograph in particular reminded me of a Henry Moore piece in the sculpture garden of the nearby San Diego Museum of Art.

Near the end of the chronological exhibit are selections from his photographs of litter to be found on the streets of New York City. Tired perhaps of looking at beautiful models all the time, “he could take a burned out Camel cigarette and elevate it to art,” Ortiz said. In that exercise, and others examining throw-away items, “he knew how to get the results that he wanted … he spent hours tweaking the lighting, getting exactly what he was looking for.”

Visitors to the MOPA exhibit will encounter four recurring themes. Juxtaposition. Death. Redefining beauty. And Penn “pushing the envelope” of his work, whether it be in subject matter, composition, or even the printing process.

It’s a thoughtful exhibit – stimulating both visually and intellectually.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

What an interesting read. I was also invited to this, but couldn’t go. I love his work though, so I have to go see it before February.