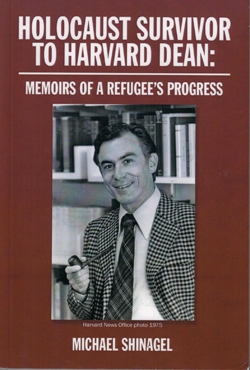

Holocaust Survivor to Harvard Dean: Memoirs of a Refugee’s Progress by Michael Shinagel © 2016, Xlibris, ISBN 9781524-509606; 150 pages plus Index; Available on Amazon.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Having served for nearly four decades as dean of the Harvard Extension School – the longest known deanship in Harvard’s history – author Michael Shinagel shares many experiences in this memoir about broadening the outreach of the nation’s premier university to people in mid-career, civil servants, promising high school students, minority group members, and many other deserving groups. Accordingly, this book will be of particular interest to two classes of readers: college educators who may wish to adapt some of Harvard’s programs on their own campuses, and Harvard alumni and aficionados who relish reading about their alma mater.

SAN DIEGO — Having served for nearly four decades as dean of the Harvard Extension School – the longest known deanship in Harvard’s history – author Michael Shinagel shares many experiences in this memoir about broadening the outreach of the nation’s premier university to people in mid-career, civil servants, promising high school students, minority group members, and many other deserving groups. Accordingly, this book will be of particular interest to two classes of readers: college educators who may wish to adapt some of Harvard’s programs on their own campuses, and Harvard alumni and aficionados who relish reading about their alma mater.

The interest of San Diego Jewish World being Jewish stories, I found myself particularly drawn to Shinagel’s accounts of how his family outran the Holocaust between 1938 and 1941; a Harvard program of the 1970s that brought Israeli, Egyptian, Turkish, and Iranian educators together – even in advance of the peace treaty reached between Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin; Shinagel’s three marriages—the first to an Episcopalian, the second to a Catholic, and then, his last, to a fellow Jew; and finally, his establishment of an ESL competition at Harvard in honor of his refugee parents.

Knowing the portent of Germany’s Anschluss with Austria, the Shinagel family moved from Vienna first to Prague, Czechoslovakia, then to Brussels, Belgium, but were unable to outrun Hitler’s blitzkriegs. His father was imprisoned but later released. They made their way to Marseilles, from which they caught a ship intended for Martinique, but after being intercepted by a British destroyer, the ship was rerouted to Trinidad. In 1941, the family finally reached New York City. Shinagel was seven years old.

The memoir plays tribute to Hiram Bingham IV, who was the American consul in Marseilles who defied State Department orders and issued visas to Jewish refugees – an American version of other brave diplomats such as Japan’s Chiune Sugihara and Portugal’s Aristides de Souza Mendes. “Without his assistance, we surely would have perished in the Nazi Holocaust,” writes Shinagel.

In 1976, an exciting experience in which he participated was a two-week long seminar involving officials from the four Middle Eastern countries. Recall that this was the time before the fall of the Shah of Iran, and it was a time when Turkey and Israel had amicable relations. But Israel and Egypt only recently had concluded the Yom Kippur War, so “it was gratifying to see the Egyptian and Israeli educators interact with each other.”

Shinagel retold a fanciful story he told at that conference about Secretary of State Henry Kissinger attempting to have a bolt of cloth tailored into a suit. The cloth had been sent to him by an admirer in honor of his winning the Nobel Peace Prize. In Germany and in England, tailors said they could make parts of the suit but not all of it. At Harvard, however, he visited a nearby Jewish tailor who said he not only could make him a suit but throw in an extra pair of pants. How was this possible? The Secretary of State asked. “Mr. Kissinger,” responded the tailor, “at Harvard you’re not such a big man.”

When Shinagel and his second wife, Rosa, served as Masters of Quincy House at Harvard, he decided to decorate the dining hall with international flags. He chose flags from Great Britain, Mexico, Japan, Israel, and France. A veteran objected to the Japanese flag, because it reminded him of the country he had fought against in World War II. A Palestinian student objected to the Israeli flag. After he took both down, Israeli students were outraged, and the fact that he was both Jewish and had relatives living in Israel did not mollify them. Eventually, he decided to limit the display of flags to those of the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Great Britain and those of the original 13 colonies. Of course, an Irishman came and objected to Great Britain’s – but it turned out he was only teasing Shinagel.

In 1995, Shinagel married his third wife, Marjorie, with his two children and her two children holding up the four corners of a tallit to make a chuppah. He later told guests at the wedding reception that he had a dream in which his parents, in heaven, discussed the matter. “Gott sei dank. Michael finally married a Jew!” applauded his mother. His father nodded approvingly. Later Shinagel’s son, Mark, whispered, “Dad, the third one is the charm!”

That same year, Shinagel decided to honor his parents, remembering how after arriving in the United States they attended classes in English as a Second Language. “I realized what an effort it was for them to go to class after a full day of working at their jobs. … I decided to honor them by establishing the Emmanuel and Lilly Shinagel English as a Second Language Prize Fund. Each semester, ESL students would write essays at their comprehension level in a competition. The winners would receive book or course scholarship prizes at an assembly meeting attended by teachers, families and friends.”

This is not a dramatic memoir, but it is a pleasant one. It contains the kinds of stories that Shinagel might relate to friends over after-dinner drinks.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com