By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Now through the end of 2020, visitors to the Museum of Man may see the “Living with Animals” exhibit, which offers new perspectives on animals that we consider pets, those that we consider pests, and those that we serve on our plates.

SAN DIEGO – Now through the end of 2020, visitors to the Museum of Man may see the “Living with Animals” exhibit, which offers new perspectives on animals that we consider pets, those that we consider pests, and those that we serve on our plates.

The idea for the exhibit originated at one of the periodic brainstorming sessions held among staff, volunteers, and board members, according to Erika Katayama, the museum’s senior director for audience engagement. At first, the idea was very general, no more than something like “let’s do something about animals,” but over time, the idea was refined. The exhibit covers an upstairs wing of the museum, yet it couldn’t include every kind of interaction between humans and animals, so some possibilities were winnowed. For example, the exhibit does not address microscopic animal life, nor does it deal with animals as carriers of diseases such as the avian flu. What it does consider are those interactions that might occur in or near someone’s home.

Katayama’s 17-year museum career has included responsibilities for education, curatorial, retail shops, visitor services, exhibitions, and cultural resources management. She arrived at the Museum of Man after this exhibit was developed by Sarah Crawford, who since has moved on to Los Angeles. Once here, Katayama’s responsibility included coordinating the work of developers, designers, and fabricators and making certain that deadlines were met, and that the budget was observed.

Unlike other museums, the Museum of Man does not typically contract with outside curators. It prefers instead to do everything in house, from creating the story boards to fabricating the exhibit. The museum has its own woodshop and workshop on the site.

Some of the information that you encounter in the “Living with Animals” exhibit may surprise you. For example, said Katayama, “if a beetle ran through my house, I might stomp on it, but across the globe, a lot of people keep them as beloved pets. If you stomped on it, they would be heart-broken.”

Some of the information that you encounter in the “Living with Animals” exhibit may surprise you. For example, said Katayama, “if a beetle ran through my house, I might stomp on it, but across the globe, a lot of people keep them as beloved pets. If you stomped on it, they would be heart-broken.”

Here in the United States, we keep dogs as pets, but in some other cultures, they are raised as food. If someone ate our pet dog, we would be heart-broken.

The museum staff intends for people to gain a different perspective about what is a pet. “Around the world, we often have different ideas,” so the purpose of the exhibit is “expanding our thinking a little bit.”

One activity within the “pets” section of the exhibit is a game involving matching owners with their dogs. In a display case, there is a collection of dog collars; elsewhere there is a small collection of crickets.

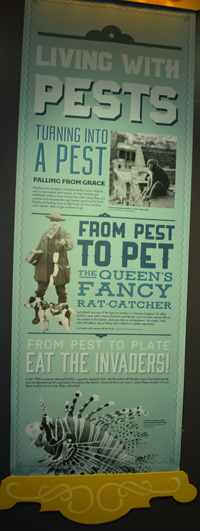

In the “pests” section are individual exhibits about pigeons, rats, and cockroaches – all of whom thrive because humanity has been so good to them. Cockroaches would perish in cold weather, if they didn’t have human dwellings where they could keep warm. Pigeons would find very little to satisfy their inherent need to perch on cliffs if humans didn’t build cities where there are rooftops, fences, telephone wires, walls, and other places for perching. And rats might have remained in central Asia, where they originated, had not travelers had suitcases, saddle bags, and other places where they could “hitchhike” rides to new destinations.

We know, of course, that pigeons and rats can play beneficial roles in human society. Rats are used in the medical research that lead to the development of life-saving pharmaceuticals. Homing pigeons can carry messages for long distances back to their home base. So even as concepts of “pets” are fluid, so too are concepts of “pests.”

In the Animals on our Plates section, there is a caution sign warning parents that they may not wish their children to see photographs of a sow being unable to move in a tight pen as she is suckled by piglets. Images of live chickens being vacuumed into a processing machine are disturbing. So is a photograph of a giant round table with slots for several scores of dairy cows, in which the cows are confined for mechanized milking.

I wondered if the intent behind this display was to promote vegetarianism.

“We leave that up to our visitors,” responded Katayama. “The idea is to encourage conversation among folks. They might talk about the way animals are being kept, about animal treatment, or possibly where they are having lunch.”

She said that children today don’t know where their food comes from. “When we go to Ralph’s or Vons, we see meat on a tray. We don’t see the animal that it came from.” Our modern era is different from previous times when many families raised their own food and did their own butchering, Katayama said. “We wanted to show people where their food comes from. For some visitors this is new information.”

Before an exhibit is undertaken, the Museum of Man questions paid visitors whether they would like to attend such an exhibit, and perhaps even pay a fee in addition to the museum’s admission charge. Ideas that receive the most positive responses then go into the development phase. Now that the exhibit is underway, visitor reaction has been positive, with some visitors returning on multiple occasions, according to Katayama.

Periodic lectures and demonstrations enhance the basic exhibit, including “Canine Ambassadors,” 1-2:30 p.m., Jan 15; “A Bee’s Life;” 1:30-2:30 p.m., Jan. 15; “Birds of Prey,” 11:30-2:30 p.m., Jan. 19; “Pets on the Page” writing workshop, 11:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m., Jan. 26; “Dogs that Serve,” 1 p.m. -2:30 p.m. Jan. 26; and “Cats that Serve,” 1 p.m. -2:30 p.m., Jan. 27. Information may be found on the museum’s website at https://www.museumofman.org/exhibits/living-with-animals/

The “Living with Animals” exhibit is included in the price of admission to the Museum of Man, which is $13 for adults; $10 for students, seniors, military, and children between the ages of 6; and free for children aged 5 and under.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com