The Spy Behind Home Plate, a documentary on the life of Moe Berg by Aviva Kempner, opening June 28 at the Landmark Ken Theater, 4061 Adams Avenue, San Diego.

By Donald H. Harrison

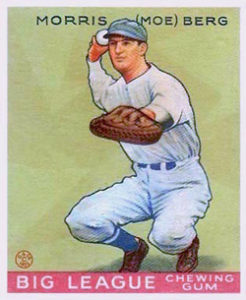

SAN DIEGO – In baseball, an all-around player is one who can hit, field, steal bases, and inspire his team mates. They used to joke about Moe Berg that he could speak a dozen languages, but he couldn’t hit in any of them. But if Berg were “good field, no hit” as a baseball scout might put it, he nevertheless was of value as a defensive player for his teams, especially after he switched from the infield to the position of catcher. He was so good behind the plate that an essay he wrote on the symbiotic relationship between pitchers and catchers – replete with literary references – became a classic. The New York Times dubbed Berg “the professor.”

Berg was more than an all-around player; he was an all-around man, with a jaw-dropping resume. He was a graduate of Princeton University with a knack for learning languages. Trading signals in Latin with other baseball players at Princeton University, he was asked what he would do if opposing team members knew Latin. “Switch to Sanskrit,” he responded. He was invited to join one of Princeton’s societies, but declined when he was told other Jews weren’t welcome.

After college he played for the Brooklyn Robins, the forerunner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. During baseball’s off season he earned a law degree from Columbia University. And after a 15-year career in baseball, with such teams as the Chicago White Sox, Washington Senators, and Boston Red Sox, he utilized his celebrity as a world-class athlete to become a spy for the United States before and during World War II.

Kempner’s documentary is both a celebration of the man as well as an interesting essay on the prejudices and cross-currents a Jew faced in the United States during the first half of the 20th century.

Berg’s father, Bernard, a pharmacist, took no joy in his son’s baseball career. It was, in his opinion, a frivolous pursuit, an occupation for other kinds of people, not for a Jew. Moe’s older brother, Sam, fulfilled family expectations by becoming a doctor. His sister, Ethel, became a schoolteacher. Berg grudgingly became a lawyer, but it was only to please his father, not because he wanted to practice law. Baseball was the life-long bachelor’s first love. His second and third might have been womanizing and traveling, which often occurred together.

On the road with his baseball teams, Berg was an inveterate newspaper reader. He would buy as many newspapers as he could, stack them up, and read them all. He was said to have a photographic memory, which served him well following his baseball career when he became a celebrity guest on the Information, Please radio program. There were few things he didn’t know; the baseball player’s breadth of knowledge was as amazing as those of modern-day Jeopardy champions like Ken Jennings and James Holzhauer.

In the early 1930s, Berg was selected for a goodwill baseball team that toured Japan, where baseball was becoming increasingly popular. Others on the team included Lefty O’Doul of the New York Giants and Ted Lyons of the Chicago White Sox. On the way over, linguist Berg had a cabin boy teach him rudimentary Japanese, enough to speak a little and to sign in his autograph in Japanese characters. Following the exhibition games, Berg stayed on in Tokyo, touring the city and experiencing its night life before traveling through other parts of Asia, and on to Europe, where he was present in Germany during the early days of the Hitler regime.

He returned to Japan on a 1934 tour with a celebrity group of baseball players that included Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees, Jimmie Foxx of the Boston Red Sox, and Charlie Gehringer of the Detroit Tigers. He and Babe Ruth became close friends on the trip, during which Berg studied his Japanese. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull wrote a letter to the U.S. ambassador in Japan to extend all courtesies to Berg, who had been recruited to learn as much about the country’s installations as he could. Wherever Berg went, he brought his movie camera, filming everywhere including the Ginza (which he playfully renamed the Ginzburg). At one point, he pretended to be bringing flowers to a hospital patient, but instead went to the top of the hospital building and shot a 360-degree panorama of the Tokyo skyline – a movie that during World War II helped Jimmy Doolittle and his raiders in their bombing runs over Tokyo.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into World War II, Berg recorded a radio broadcast in Japanese, telling the people of Japan there had been no good reason for war between the two countries.

He later was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services, which was the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, to be a spy in Europe. His most important assignment was to go to Italy, while it was breaking free of Nazi control, and to learn from Italian scientists any information that they could provide about the Germans’ program to develop an Atom Bomb.

Eventually, through his sources, he was able to track down Nobel Prize winning German physicist Werner Heisenberg, who headed Nazi research into atomic fission. Heisenberg was giving a speech in Zurich, in neutral Switzerland, and Berg posed as a German-speaking Swiss college student. Berg’s assignment was to listen carefully to Heisenberg’s speech, and if it appeared that Germany was making headway in atomic research, to assassinate him. Berg had a pistol in one pocket and a cyanide capsule in the other.

Heisenberg didn’t talk about the possibility of atomic energy; instead focusing on his theories regarding the “scattering matrix” or “S-Matrix” of quantum mechanics. Berg kept his gun and cyanide pills in his pockets, concluding correctly that the Germans were not as far along in atomic research as the United States.

Filmmaker Kempner has done a remarkable job of weaving together the many strands in the life of a most remarkable man. I recommend this documentary for baseball lovers, historians, and those with an interest in American Jewish life.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com