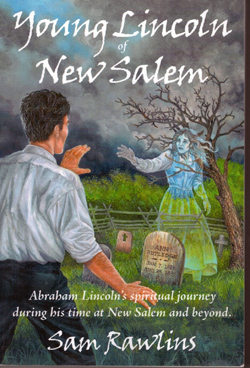

Young Lincoln of New Salem by Sam Rawlins; © 2019; Yorkshire Publishing; ISBN 9781848-231946; 333 pages including author’s notes, acknowledgments and bibliography.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Lincoln biographers tell us that as a boy the 16th President of the United States read Parson Mason Weems’ Life of George Washington. In my reading of this modern-day novel by Sam Rawlins about Abraham Lincoln’s years as a store clerk and budding politician in New Salem, Illinois, I was reminded of how Weems made up fanciful, yet pleasing, stories about a President to inspire the youth to be the best they can be.

SAN DIEGO – Lincoln biographers tell us that as a boy the 16th President of the United States read Parson Mason Weems’ Life of George Washington. In my reading of this modern-day novel by Sam Rawlins about Abraham Lincoln’s years as a store clerk and budding politician in New Salem, Illinois, I was reminded of how Weems made up fanciful, yet pleasing, stories about a President to inspire the youth to be the best they can be.

Whereas Weems’ presented some tall tales as truth – like the story about a youthful Washington not being able to tell a lie and confessing that he chopped down the cherry tree, or the one about Washington throwing a coin across the Rappahannock River – Rawlins, in contrast, admits from the outset that his Young Lincoln of New Salem is a novel. Novelists, of course, are free to take liberties with the truth; they do not operate under the constraints of historians.

In telling the story of young Lincoln and his love for Ann Rutledge, who tragically died at age 22, Rawlins presents Lincoln’s father, Tom, as an abusive drunk, who shattered Lincoln’s sense of self-worth and whose malign influence on Abraham only could be countered by the spiritual Ann. In Rawlins’ account, Ann believed in Abraham and persuaded him that God intended him for greater things.

Another villain in Rawlins’ novel is John “McNeil” McNamar, who became Rutledge’s fiancé. In Rawlins’ story, Ann and Abraham already were in love, but she had to give into McNamar’s demands that he marry her. In Rawlins’ account, McNamar threatened that if she didn’t agree to marry him, he would dispossess her parents from the family home.

Neither the descriptions of Tom Lincoln nor of John McNamar jibed with what I remembered reading about the two men, so I repaired to the David Herbert Donald biography of Lincoln as well as to a more famous biography by Carl Sandburg to see if Rawlins’ characterizations could be corroborated.

About Tom Lincoln, Sandburg wrote: “Tom Lincoln worked hard and had a reputation for paying his debts. One year he was appointed a ‘road surveyor’ to keep a certain stretch of road in repair, another time was named appraiser of an estate, and an 1814 tax book [when Abraham was 2] listed him as 15th among the 98 property owners named.” In 1823, when Abe was 11, Tom Lincoln was received into the Pigeon Creek (Indiana) Baptist Church and the following year was elected “with two neighbors to serve as a committee of visitors to the Gilead church, and served three years as a church trustee. Strict watch was kept on the conduct of members and Tom served on committees to look into reported misconduct between husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, of neighbor against neighbor.”

When the Lincoln family was about to move in 1829 to Illinois, when Abe was 17, the Pigeon Creek Baptist Church wrote a letter describing Tom Lincoln and Abe’s stepmother Sarah as members in good standing. By the time the family moved again, to another new town in Illinois, Abe did not follow; instead, he took a job with Denton Offrut delivering farm products on an 80-foot long boat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans.

David H. Donald wrote that Tom Lincoln was “generally an easygoing man, who according to Dennis Hanks ‘could beat his son telling a story – cracking a joke. … Thomas Lincoln was not a harsh father or a brutal disciplinarian. … The father would not tolerate impudence. When Abraham as a little boy thrust himself into adult conversations, Thomas sometimes struck him. Then as (cousin Dennis) Hanks recalled, young Abraham ‘never balked, but dropt a kind of silent unwelcome tear, as evidence of his sensations.”

Biographer Donald went on to say that as Abraham became a teenager, he “began to distance himself from his father. His sense of alienation may have originated at the time of his mother’s death, when he needed more support and compassion than his stolid father was able to give. It increased as the boy got older. Perhaps he felt that his place in the household had been usurped by the second family Thomas Lincoln acquired when he remarried; contemporaries noted that Thomas seemed to favor the stepson, John D. Johnson, more than he did his own son.”

Another difference that drove Abraham and Thomas apart was religion, a difference that seems to undercut the premise of Rawlins’ book, in which Abe and Ann Rutledge seem to drop God’s name into every conversation. Donald quoted Abraham’s stepmother as saying that “‘Abe had no particular religion – didn’t think of these question[s] at that time, if he ever did.’ That difference appears to have led to the sharpest words he ever received from his father. Though Abraham did not belong to the church, he attended the sermons, and afterward, climbing on a tree stump, he would rally the other children around him and repeat – or sometimes parody – the minister’s words. Offended, Thomas, as one of the children recalled, ‘would come and make him quit – send him to work.’”

When he was older, Lincoln was “reluctant to accept any creed,” Donald wrote. “His parents’ Baptist belief in predestination was deeply ingrained in his mind, though he felt more comfortable in thinking that events were foreordained by immutable natural laws than by a personal deity. To his cool, analytical mind the ideas of the evangelists were less persuasive than those of the few local freethinkers, who gathered about the store cracker barrel and, when there were no customers in sight, engaged in speculation about the literal accuracy of the Bible, the Virgin Birth, the divinity of Christ, and the possibility of miracles.”

And what of Ann Rutledge and John McNamar, the latter of whom novelist Rawlins presents as so evil you can imagine him chuckling cartoon character-like as he twirled his mustache? Biographer Sandburg presents their relationship quite differently. “The one person most anxious about him (McNamar) when he went away from New Salem in 1832 was, in all probability, the 19-year-old Ann Rutledge. They were engaged to marry and it was understood he would straighten out affairs of his family in New York State and in not too long a time would come back for the marriage. …” But it was more than two years before McNamar came back. Sandburg said Lincoln “could hardly have been unaware of what she was going through… Did she talk over with Lincoln, the questions, bitter and haunting, that harassed her? Had death taken her betrothed? Or was he alive and any day would see him riding into New Salem to claim her? And again, possibly, she kept a silence and so did Lincoln, and there was some kind of understanding beneath their joined silence.”

Donald wrote that young Lincoln was “extremely awkward” around women, but Ann Rutledge was one to whom he was attracted. She had fair skin, blue eyes, auburn skin, stood 5’3, and weighed between 120 and 130, and if others called her “plump,” that was the shape of a woman to which Lincoln gravitated. Donald speculated that if Ann had not been engaged, shy Abe would have kept his distance from her “because he was always afraid of intimacy. But since Ann was committed to another, he was able to keep up a joking, affectionate relationship with her.”

“How that friendship developed into a romance cannot be reconstructed from the record,” Donald continued. “No letter from Ann Rutledge is known to exist, and in the thousands of pages of Lincoln’s correspondence, there is not one mention of her name. Apart from one highly dubious anecdote about a quilting bee there are no stories about the courtship, which, because of Ann’s ambiguous relationship to McNamar, was intentionally kept very quiet… Sometime in 1835, Lincoln and Ann came to an understanding. … Both parties had reason to hesitate. Lincoln, who had no profession and little money, doubted his ability to support a wife. Ann strongly felt ‘the propriety of seeing McNamar, [to] inform him of the change in her feelings and seek an honorable releas[e] before consum[m]ating the engagement with Mr. L. by marriage.’”

So, by reading these two sources, we are confronted with the realization that novelist Rawlins employed quite a bit of dramatic license in telling the story of Ann Rutledge and Abraham Lincoln. The major themes of their relationship, as Rawlins’ tell it, were unfailing trust in God and the power of prayer, a burning desire on both their parts to improve themselves educationally, a high degree of civility toward each other and everyone else that they met, and absolute honesty in their dealings with all.

Weems and Rawlins both tried to inculcate similar values in their respective stories about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, two of America’s most iconic leaders. It’s a pity that they both had to stray from the truth.

Yet, critical as I am about these departures from the facts, I can’t help but admit that I liked parts of Rawlins’ book because I thought that the lessons he attempts to teach – however flawed in the telling – stand in contrast to the utter lack of civility and honesty that so characterize our sharply partisan politics of today.

Perhaps if youngsters grow up desiring to emulate Abe Lincoln – even the fictional Lincoln of Rawlins’ design – they’ll want to emulate the high standards of moral conduct that novelist Rawlins’ hoped to impart.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com