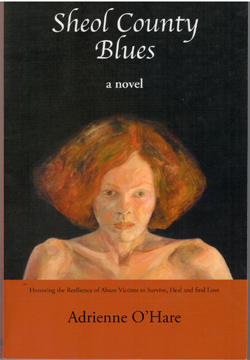

Sheol Country Blues by Adrienne O’Hare, Asna Publishing © 2019, ISBN 9780578-507248; 165 pages, $18.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – I met the Jewish lady whose name sounds very Irish (thanks to her marriage to the affable Larry O’Hare) in February 2018 at shipboard Shabbat services aboard the MS Maasdam, which then was sailing between the ports of Sydney, Australia, and San Diego, USA. With plenty of relaxing sea dates on that cruise, we had the opportunity to sit down together for a lengthy interview about her life and career as a psychiatric social worker. (That interview may be accessed here.)

SAN DIEGO – I met the Jewish lady whose name sounds very Irish (thanks to her marriage to the affable Larry O’Hare) in February 2018 at shipboard Shabbat services aboard the MS Maasdam, which then was sailing between the ports of Sydney, Australia, and San Diego, USA. With plenty of relaxing sea dates on that cruise, we had the opportunity to sit down together for a lengthy interview about her life and career as a psychiatric social worker. (That interview may be accessed here.)

In naming the county where the action of this novel takes place “Sheol,” O’Hare signaled her Jewish upbringing. “Sheol” in the Hebrew Bible is the dark place of waiting where souls go following their bodily deaths. Sheol County, in this story, is where two foster sisters, who are both survivors of childhood sexual abuse, try to cope with the lives left to them after their childhoods were stolen.

The foster sisters had separated after they grew out of the foster system, but they were reunited in a mental ward of a hospital. Skye worked there as a technician. To her surprise, Geena was one of the patients whom she had to tend. A “frequent flyer,” Geena had once again been admitted involuntarily after purposely cutting herself.

Skye was about to be fired about the same time Geena was to be released, so she agreed to follow her sister to a trailer park across the street from a rural diner where Geena worked as a waitress. Geena prevailed on the managing owner of the diner, her aunt, to hire Skye.

The novel is a story of trauma and the difficulty of recovery.

Geena will have sex with almost any man who comes along, so worthless does she feel. At least when humping with them in bed, she feels alive. To keep herself thin for them, she eats and purges. It’s when she’s left alone that she’s prone to cutting herself, hoping that seeing the blood that runs through her veins will be proof that she is still living.

Skye, whose stepfather molested but never penetrated her, considers herself a “technical virgin.” She cannot abide anyone’s touch, neither a male’s nor a female’s. Yet, she hungers for intimacy.

The two had become foster sisters after they were removed from their respective homes. They lived together with Mrs. Gibbs, who was kindly and looked after them until they became adults, but who was powerless to excise the demons that haunted them.

Skye suffers nightmares perhaps as frightening as any endured by combat veterans. She keeps a knife under her pillow just in case an intruder might awaken her.

Her mental agony one day is compounded by news that her mother – whom she blames for not protecting her from her stepfather – has only a few days to live and wants to see her. Skye’s emotions of rage and regret practically paralyze her. On the one hand, she hates her mother for her terrible negligence. On the other hand, she remembers the sweet mother-daughter relationship they had before the stepfather, now dead, came into their lives.

So, the two sister victims are in a kind of Sheol. Thanks to O’Hare’s experiences as a psychiatric social worker, we gain a deeper understanding—and sympathy—for their illnesses.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com