RICHMOND, California – Identical books with different titles and different covers introduce bookish mystery and confusion. Such is the case of No Place to Lay One’s Head and A Bookshop in Berlin by Françoise Frenkel which first appeared in 1945 as Rien où poser sa tête. The revival of an overlooked book has a special attraction. Publishers appeal to sensibilities of prospective readers through alluring titles and cover art.

RICHMOND, California – Identical books with different titles and different covers introduce bookish mystery and confusion. Such is the case of No Place to Lay One’s Head and A Bookshop in Berlin by Françoise Frenkel which first appeared in 1945 as Rien où poser sa tête. The revival of an overlooked book has a special attraction. Publishers appeal to sensibilities of prospective readers through alluring titles and cover art.

As the years since the Holocaust mount we are reaching the point where the generation of eyewitness survivors disappear. Their memories are in books and videotapes. It is unknown how many aged manuscripts in attics, trunks and archives are yet to be disinterred. Then there are the obscure published accounts, like Frenkel’s 1945 work that are rediscovered, revitalized and revalued, sort of like on Antique Road Show.

Frymeta Idesa Frenkel, born in Poland in 1889, a Francophile who attended the Sorbonne and changed her first name to Françoise. A passion for French literature led her to the bouquinistes on the Seine, the subject of many Parisian sketches. She wanted to spread French culture outside of France.

Françoise married Simon Raichenstein, a Jewish Ukrainian who had fled the Bolsheviks. Curiously he is never mentioned in the book. They moved to Berlin in 1921 and opened a bookstore specializing in French books and magazines, Maison du Livre français in Berlin. The business plan had bizarre elements. Imagine a Polish Jew opening a French language bookstore in Berlin shortly after the Germans lost the Great War. The bravery of Françoise and Simon, and their joie de livre is far more intrepid than Sylvia Beach in 1919 opening the English language bookshop Shakespeare & Company in ally-friendly Paris. German and Central Power resentment of the Treaty of Versailles, war guilt, reparations, and what Adolph Hitler called the stab in the back fermented into World War Two.

Maison du Livre français catered to Berlin’s small French community and larger community of Russian anti-revolutionaries, many of whom appreciated French culture. The bookstore with international cachet worked around German bureaucracy and remained open after the Nazi rise to power in 1933. Simon’s passport was suspect and he returned to Paris in 1933. He would be murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. German authorities confiscated some books in 1935. Kristallnacht in November 1938 was a clear warning of worse to come.

Françoise left for Paris in 1939. The first 20 percent of the book covers 1921 to 1939. The balance of the book covers 1940 to 1943. There are harrowing tales of hunger, flight, imprisonment, but in 1943 she escaped from the clutches of Nazis and Vichy collaborators by fleeing across the border into Switzerland. She found repose, “a place to lay her head,” and published Rien où poser sa tête in September 1945.

The book was reviewed in April 1946 in the Franco Swiss feminist journal, Le Mouvement féministe. The two paragraph review, about 150 words, was perhaps the only notice the book received. Both the publisher and journal have gone out of existence. The major international library catalog, the online WorldCat, a collaborative of 17,900 libraries in 123 countries with 2.8 billion library assets, indicates copies of the 1945 edition only in Geneva; Lyon, France; and one at YIVO, the Yiddish Scientific Institute, in New York.

There is a murkiness in the book’s rediscovery. After the war Frenkel settled in Nice and died there in 1975. According to various book review accounts a copy of her book was found in 2010 in an attic, and then went to a car boot sale, flea market, Bric-à-brac sale and the “Emmanaus Companions charity jumble sale” in Nice.

The refound volume excited interest, was read and taken to a publisher to consider reprinting.

The new French 2015 edition contains a preface by Patrick Mondiano who received the 2014 Nobel Prize for literature for his contribution to “the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destiny and uncovered the life-world of the [Nazi] occupation.” Mondiano was born two months before before Frenkel’s book was published.

The book reemerged at a pivotal time. The flurry of publishing and translation starting in 2015 is linked to the Frenkel’s 2010 rediscovery, Modiano’s 2014 Nobel Prize, the surge of human migration increasingly at odds with national borders and xenophobic sentiments, and the resurgence of anti-Semitism.

In 2003 Stephanie Smee, an Australian attorney, turned from her legal career to her passion of French translation. Her English translation of Frenkel’s WWII memoir was published in English by the Vintage imprint of Penguin Random House, Sydney, Australia, in 2017; by Pushkin Press in London in 2018; and Simon & Schuster’s Atria imprint in the US in 2019. No Place to Lay One’s Head, a translation of the 1945 French title, subtitled, A Tale of dignity and desperation in Vichy France hews to the spirit of the French title, evoking refugees, the homeless and stateless. In New York, Simon and Schuster retitled the book, A Bookshop in Berlin; The Rediscovered Memoir of one Woman’s Harrowing Escape from the Nazis. Smee was asked what constituted a good translation. She responded lawyerly, “I think the short point is: we know it when we read it.”

The book stands for decency and the “kindness of strangers” — Françoise was helped with food, sanctuary, shelter, forged documents, transport and directions by several people that Yad Vashem could identify as “righteous gentiles.” There were also zealous Nazis, incompetent smugglers, and people willing to turn a blind eye. Frenkel wrote, “One could write volumes about the courage, the generosity, the fearlessness of those families who offered assistance to fugitives in every département and even in Occupied France, putting their lives at risk.” Françoise claimed to be “the beneficiary of one generous gesture after another!” She dedicated her book to “Men and women of goodwill.”

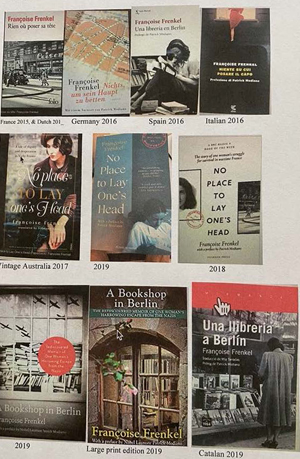

Since 2015 the book has been translated into Catalan, Dutch, English, German, Italian, and Spanish. At least ten different covers adorn the book. It’s a little disconcerting that some of the WorldCat entries classified the book as “fiction.” The English editions have received encouraging reviews in at least fifteen print and online journals including Independent, The Muslim Times, The Statesman, Financial Times, The Economist, The Spectator, Telegraph, The Times of Israel, Asymptote, Publishers Weekly, Wall Street Journal, Kirkus, The Jewish Chronicle, The New York Times, and Forward. The French edition, and the translations have garnered several more reviews.

Frenkel’s work has been compared to the Diary of Anne Frank and Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française. There are differences. Anne Frank, a German child hidden in Holland, was murdered in 1945 at Bergen Belsen. Her father Otto shepherded the diary to publication in 1950. Némirovsky, from the Ukraine, living in France, was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. Her early 1940s manuscript received the light of day in the late 1990s and was published in 2004. Anne Frank and Némirovsky wrote, perished and were published posthumously. Frenkel wrote, published, survived and was ignored until rediscovered. She entered the Holocaust canon with quality and significance, winning the 2019 Jewish Quarterly Wingate Prize. The book lay dormant in a few Swiss and French libraries and at YIVO in New York. has been been given new life through the efforts of publishers, translators and an inquiring reading public. Wall Street Journal book reviewer Diane Cole described Frenkel’s experience a “constellation of luck and chance.” She transformed vicious chaos into rewarding reading. Frenkel’s book is now in at least 700 libraries around the world.

*

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com