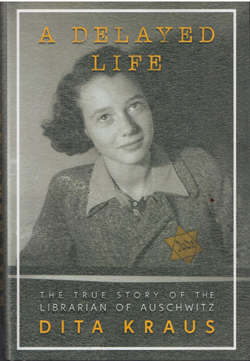

A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz by Dita Kraus; Feiwel and Friends, 2020; 9781250-760890; 339 pages, $24.99.

SAN DIEGO – Antonio Iturbe, a Spanish author, wrote a fictional account of Dita (Polachova) Kraus’s life titled The Librarian of Auschwitz, in which Dita was cast as a heroine who risked her life to expose children at the notorious Nazi death camp to a few books on diverse subjects. The point of the story, for many, was that in spite of the inhumanity all around them, there were people for whom kindness, literature, learning, and knowledge remained paramount objectives.

SAN DIEGO – Antonio Iturbe, a Spanish author, wrote a fictional account of Dita (Polachova) Kraus’s life titled The Librarian of Auschwitz, in which Dita was cast as a heroine who risked her life to expose children at the notorious Nazi death camp to a few books on diverse subjects. The point of the story, for many, was that in spite of the inhumanity all around them, there were people for whom kindness, literature, learning, and knowledge remained paramount objectives.

Now comes Kraus’s own memoir of her remarkable life, which gives us a fuller picture of who she is, and the experiences she had pre- and post-Auschwitz.

Laden with anecdotes, this book is divided into three parts. Part I tells of her childhood in Czechoslovakia and profiles various family, friends, and neighbors. Her grandfather was a respected legislator and judge. Many of her friends and neighbors were Christians, who remained friendly and caring for Dita’s family notwithstanding the demonization of Jews by the Nazis who took over the country, nor the many rules and regulations forbidding fraternization between Jews and non-Jews.

From Prague, the story moves in Part II to Terezin, the so-called model concentration camp to which the Nazis invited the Red Cross and other representatives of international agencies in an effort to persuade the world that Jews were being humanely treated. Among the cultural activities permitted at Terezin (known to the Germans as Theresienstadt) was the production of the children’s opera Brundibar, in which Dita performed in the choir. This was not a permanent assignment; children in the opera company were constantly being sent on transports to Auschwitz, only to be replaced by other youngsters as the charade continued. We in San Diego remember another Holocaust survivor who also was a member of that opera company a year before Kraus was – the late Eve (Wertheimer) Gerstle who died in 2015 at age 101. Like Kraus, Gerstle often lectured audiences about her Holocaust experiences.

At Auschwitz, Kraus was sent to the “family camp” with her mother; her father, having preceded her, was nearly unrecognizable from lack of food and over work. He died just a few weeks after Dita arrived. Thanks to Fredy Hirsch, whom she had known at Terezin and who now was the Jewish supervisor for a daycare facility in the family camp, Dita was assigned at age 14 to the Kinderblock, which like Terezin before it was a propaganda venue created by the Germans.

“Hirsch appointed me to be the librarian of the smallest library in the world,” she wrote. “My role was to watch over the twelve or so books that constituted the library. The books were a random collection. On the ramp, thousands of Jews arrived daily. They were led away, but their luggage remained behind. A number of lucky prisoners had the task of sorting their contents. When they found a book, they would somehow get it to the Kinderblock.” Older children would memorize the content of the books, then capsulize them in story-telling sessions to younger children.

Before long, however, Dita and other prisoners in the Kinderblock were ordered to report to a “selection” in front of Dr. Josef Mengele, the doctor who decided whether an inmate should be gassed or kept alive to be worked to death. At this selection, Dita’s mother was picked for the gas chamber, but she was able to sneak from that line to the one in which Dita had been sent. As a result, they were transported together by box car to the Friehafen camp of Hamburg, Germany, where Dita was assigned to pick up debris from sometimes nightly Allied air raids. Next, she went to assigned to Neugraben where she dug trenches and the foundation for an air raid shelter. Near the end of the war she was moved again to Tiefstack, where she worked in a factory producing cement blocks. And finally, she was sent to the notorious Bergen-Belsen, where she was liberated by the British Army.

Part III tells of Dita’s life after liberation. With no other family, she and her mother remained at Bergen-Belsen, which was converted into a camp for displaced persons. Her mother sickened there and died, leaving Dita orphaned.

At that point still a teenager, Dita returned to her hometown of Prague, where she lived until the Communist takeover. There she recognized Otto Kraus, who had been one of the educators in the Kinderblock at Auschwitz. Able to talk to each other about their experiences, which they could not explain to others who had not been at Auschwitz, they eventually decided to get married. It was more a practical decision than a romantic one. But they learned to love each other, and eventually made their life together in Israel, where initially they lived and worked on a kibbutz, and later moved to their own home. Otto and Dita both taught English there. Years later, after Otto died, Dita traveled regularly to Prague, eventually deciding to split her time between the two countries, lecturing in both about the Holocaust.

She and Otto had two sons and a daughter who died as a young woman from a genetic disease. Her children have gone on to become parents themselves and “despite Hitler’s efforts to exterminate us, there re now fourteen Kraus descendants—the last one, my great-granddaughter, Michelle …”

Although the title of the book highlights the library experience, this really was just an episode in Dita’s crowded life. I personally found myself most enjoying her accounts of kibbutz life in Israel, when the country was still poor and living there was the stuff of pioneers. Wherever she went, Dita was a keen observer with a flair for description, not only of places but also of the many people whom she met. The book is well worth reading.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com