RICHMOND, California — I am sheltering in place. The health departments of the six Bay Area Counties have ordered stringent social distancing to protect all of us, seniors included. I’m more than a bit of a nut about epidemics and pandemics. Inconvenience, the library is closed indefinitely. I cannot check out books or expect interlibrary loan to deliver necessary books, so I rely on my home library, MacBook, memory, and cell phone.

RICHMOND, California — I am sheltering in place. The health departments of the six Bay Area Counties have ordered stringent social distancing to protect all of us, seniors included. I’m more than a bit of a nut about epidemics and pandemics. Inconvenience, the library is closed indefinitely. I cannot check out books or expect interlibrary loan to deliver necessary books, so I rely on my home library, MacBook, memory, and cell phone.

I have six different English language editions of The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), originally written in Italian in 1353. It’s a beautiful ribald romp of young people fleeing an Italian city beset by the Black Death, which originated in Asia. The young adult men and women go to the country and instead of playing cards, scrabble, boggle, Monopoly or Rummy cube, they beguile each other by telling irreverent stories.

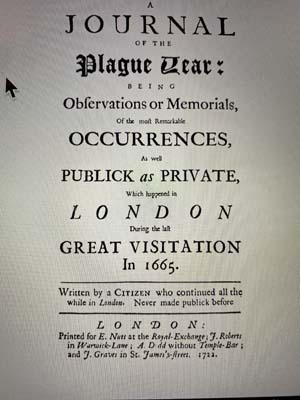

The plague has interested me for over 60 years. On my shelves I have Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year 1665; William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (1976); John Aberth, the author of The Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348-1350 (2005), the first of his several studies on mass mortality; Teofilo F. Ruiz, The Terror of History, on the Uncertainties of Life in Western Civilization (2011); and Rachel Kadish, The Weight of Ink (2017). I knew people who suffered through the 1918 Influenza epidemic. And I know three of the above mentioned authors. One of the first books I received as a gift was Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

I’ve got clean water, garbage collection, mail delivery, electricity, three months’ supply of medications, a full refrigerator and freezer, and offers from younger family and friends to go shopping for us. Television, cable, cell phones, face time, computers, real newspapers, and a well-stocked liquor and wine cellar are creature comforts undisturbed. The question is what do pandemics mean for the Jews.

Surfing “Jews, plagues, epidemics, and pandemics” on my MacBook and iPhone produced two interesting results. “The Jews of London and the Great Plague (1665)” by Wilfred S. Samuel came on the screen in a microsecond. He presented it orally to the Jewish Historical Society of England in December 1936 and published in 1937, amidst Germany hosting the Olympics and Hitler ramping up power in Europe while Stalin purged imaginary dissidents. The article was on JSTOR (perhaps the second best library invention after WorldCat). I signed into the library and printed the 10-page article.

Jews had been expelled from England by King John in 1290. They were readmitted to England by Oliver Cromwell the leader of the Commonwealth in 1656. There were about 250 Jews in the English capital with Portuguese and Spanish heritage from Amsterdam. The Black Death felled some Jews who were buried in cemeteries.

Surviving records indicate the living were concerned with intermarriage between Christian and Jews, their offspring, and who should be responsible for their welfare. Before unemployment insurance and Social Security, the poor and the vulnerable were cared for in poor houses and by co-religionists. Jews took care of their own, who else would? The curse of becoming a “public charge” is behind much of American immigration legislation since the 19th century. Why should white nativists pay for the care of the “indigent, dirty, criminal foreigners?”

Where should a Jewish man with a Protestant, or a Jewish woman converted to Christianity, and their children, go for assistance? The magistracy determined that the Jewish community was responsible for maintenance. In December 1701 Parliament passed “An Act to Oblige the Jews to Maintain and Provide for their Protestant Children.”

The 1665 plague features more dramatically than academically in The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish. She will be speaking at the newly formed Jewish Women’s Archive “Quarantine Book Club” on March 19, 5 pm PDT.

Donald G. McNeil, Jr. is a science and health reporter for The New York Times specializing in plagues and pestilences. He covers diseases of the world’s poor, including AIDS, Ebola, malaria, swine and bird flu, mad cow disease, SARS and Covid-19. On September 1, 2009 he published “Finding a Scapegoat When Epidemics Strike” in The New York Times. He writes that between 1348 and 1351 more that 200 European Jewish communities were severely disrupted and demonized. Minorities, newcomers and the “other” bear the brunt of xenophobia. I don’t have any books on the 1918 Influenza. McNeil recommends The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (2005) by John M. Barry who teaches at Tulane University, and points out the Spanish flu was actually the Kansas Flu having started in Haskell County. The 30 copies on abebooks run from $19.72 to $1,027.04, with free shipping; opportunist gouging, or investment?

McNeil’s most recent New York Times article appeared on February 28, 2020, “To Take on the Coronavirus, Go Medieval on It.” And here, as a consequence I sit. This novel March madness promises to stretch through other sports seasons, we are in it for the long haul. Experience may foster optimism or pessimism, but sheltering in place is a tortuous blessing for quiet reading, says the optimist; Healers, scapegoats and victims litter our history.

*

Oliver B. Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com