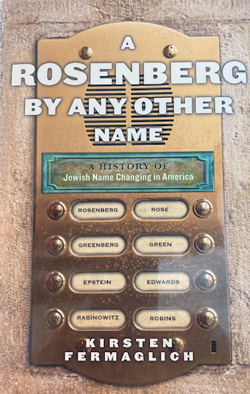

A Rosenberg by any other name: A history of Jewish name changing in America by Kirsten Fermaglich; New York: New York University Press, 2018; 245 pages, $28.

RICHMOND, California — You gotta love this book. Page 1 leads with my favorite “Ferguson” (shayn fergessen) joke which I have retold tirelessly for years. Fermaglich reveals that Winona Ryder, born in Winona, Minnesota and currently playing the role of Evelyn Finkel in the Netflix series The Plot Against America, based on Philip Roth’s 2004 novel of the same name, was born Winona Laura Horowitz. But this book is not about jokes and celebrities but about the real choices that the nearly three million Jews who came to America between 1880 and 1920 had to make to feel comfortable and make progress in America.

RICHMOND, California — You gotta love this book. Page 1 leads with my favorite “Ferguson” (shayn fergessen) joke which I have retold tirelessly for years. Fermaglich reveals that Winona Ryder, born in Winona, Minnesota and currently playing the role of Evelyn Finkel in the Netflix series The Plot Against America, based on Philip Roth’s 2004 novel of the same name, was born Winona Laura Horowitz. But this book is not about jokes and celebrities but about the real choices that the nearly three million Jews who came to America between 1880 and 1920 had to make to feel comfortable and make progress in America.

There are several permutations of Green, Greenberger (mountain), Greenberg, Greenbaum (tree), Greenwald (forest), Greenspan, Greenstein (stone), Gruener, Greenspohn, Greenspoon, all people I know, or authors I’ve read. Two generations ago they may have considered becoming Greene or Green but not Vert or Verde. My wife’s maiden name is Goldstein, which some American and Canadian relatives turned to Gold and Gould but not Oro. Name changes did not happen per the old canard that immigration bureaucrats at Ellis Island and other Ports of Entry inflicted new monikers on greeners. They were conscious choices that had financial and psychological consequences.

Colleagues advised Felix Frankfurter that a more American name would go better in the Boston legal community; he stood his ground. There is some gratuitous inconclusive name dropping.

The author mentions President Obama’s 2016 Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, and opens an additional name changing venue. The judge’s grandfather, Max Garland, left England with that name.

My last name, Pollak, is frequently misspelled Pollack, Pollok, Pollock and can also be found with just one l. Pollak, sometimes transformed by my spellchecker “thinking” it should be Pollack, is Austro-Hungarian, not Polish, and the “o” is soft. In some university classes I taught, as many as 70% of the students turned in papers misspelling my name, even though Pollak appeared clearly on the exam and syllabus. And pronouncing Pollak, and hearing it mispronounced, correcting or instructing the speaker on how we want it sounded, have been burdens in England and America. In the early 1950s my father toyed with changing our name to Pollard. But like Frankfurter, my father whose first name changed, depending on where he lived from Vilhelm, to Villem, Hillel, William, and Bill, stuck to surname of habit, maintaining patrimony despite the occasional irritation of misspelling, difficult pronunciation, and foreign sounding nature.

Professor Fermaglich’s sampling methodology included reviewing every name change petition filed in the Civil Court of New York City in five year intervals, and reviewing one petition in ten for every year from 1887 to 2012. When in doubt about the uncertainty of the first or last name she did not count them as Jews.

Name changing applications identified several reasons to change: Anti-Semitism, finding jobs, entry into the college of choice, entry into the middle class, professional advancement, neutralizing private unofficial anti-Semitism, dropping foreign sounding too difficult to pronounce names, emotional anxieties, humiliation, exclusion, social isolation, ridicule, discomfort, embarrassment, hindrance, cumbersome, impediment, stigma, confusion, annoyance, inconvenience, negative evaluation, potential for discrimination, genteel discrimination in housing, hotels, and other social accommodations. All could hopefully be vitiated by Americanizing resulting in a better future,

Psychologist Samuel Calmin Kohs in 1942 developed a list of 106 “Distinctive Jewish Names.” The listed started with Abraham and five variants and ended with Zuckerman. This panoply of Jewish names is a most useful research tool, good up to the mid-twentieth century.

During 1946 the highest number of name change petitions were filed for the entire 20th century. Jewish accounted for more than 50% of those petitions. Critics accused the name changers of lack of pride, self-loathing, and self-hatred. Name changes fostered “passing” and “cover.” Gentleman’s Agreement by Laura Z. Hobson appeared in print and in the movie theaters in 1947. Elia Kazan directed it, and in 1949 he directed Pinky about a light skinned African American woman. Sociologist Erving Goffman studied the role of self-representation and the avoidance of stigma in the the 1950s.

Some changed their names through marriage, intermarriage, conversion, crossing religious lines, or went secular and invisible, shedding and escaping and denying the Jewish faith, community, culture and heritage. But apostasy was not typical for name changers, most of whom typically did not leave the Jewish community. However, my review of recent obituaries, people named Bloom, Blumstein, Glass, and other names that you could count on as being reliably Jewish up to 1950, indicated the decedent’s last rites and burial occurred in Christian cemeteries. And, I should add, several East Bay Jewish cemeteries indicate Christian spouses with a cross on the tombstone.

After WWII anti-discrimination legislation imposed some “color-blind” protections. Job applications could no longer ask for parents’ places of birth or mother’s maiden name. The university quota system, the Harvard Plan, Affirmative Action, and the Supreme Court’s decision in the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke are a permutation of name changing aspirations. The incidence of name-changing shifted to African Americans, Asians, Latinos, and people from the Middle East. It was frequently used to reinforce ethnic identification. For instance, in 2012, only one-third of petitioners with Middle Eastern names sought to erase their ethnic names to improve social mobility, while in 1946, 87 percent of Jewish name changers had that intent.

The author earned her doctorate in history at New York University in 2001. She is an Associate Professor of History and Jewish Studies at Michigan State University. Her previous books include American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares (2006).

*

Oliver B. Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com

Thank you. Have spent many hours on Facebook trying to refute the name-change-at-Ellis Island myth. Great article.

Brian G. Andersson

The Bronx, NYC