The Golden Flea, A Story of Obsession and Collecting by Michael Rips

TETON VILLAGE, Wyoming — Disclosure. I am a Michael Rips fan and enjoy his literary non-fiction. In 2003 we visited New York. I wrote, “I stopped at W. H. Smith bookstore at Omaha’s Eppley Airport for some airplane reading. Nothing attracted me. An energetic Waterstones salesman persuaded me to purchase Pasquale’s Nose, by former fifth generation Omahan Michael Rips. His enchanting quirky Tuscan romp prompted me to call him at the Chelsea Hotel and arrange a Sunday breakfast at The Antique Café in Chelsea. Michael gave us a tour of Chelsea and the Sunday Flea market scene. We met his wife, Artist Sheila Berger, and their five year old daughter, Nicolaïa. We parted with words of friendship. Give yourself a treat, read Pasquale’s Nose.” Subtitled Idle Days in an Italian Town (2001) it was written while painter and sculptor Sheila practiced her art in Italy.

TETON VILLAGE, Wyoming — Disclosure. I am a Michael Rips fan and enjoy his literary non-fiction. In 2003 we visited New York. I wrote, “I stopped at W. H. Smith bookstore at Omaha’s Eppley Airport for some airplane reading. Nothing attracted me. An energetic Waterstones salesman persuaded me to purchase Pasquale’s Nose, by former fifth generation Omahan Michael Rips. His enchanting quirky Tuscan romp prompted me to call him at the Chelsea Hotel and arrange a Sunday breakfast at The Antique Café in Chelsea. Michael gave us a tour of Chelsea and the Sunday Flea market scene. We met his wife, Artist Sheila Berger, and their five year old daughter, Nicolaïa. We parted with words of friendship. Give yourself a treat, read Pasquale’s Nose.” Subtitled Idle Days in an Italian Town (2001) it was written while painter and sculptor Sheila practiced her art in Italy.

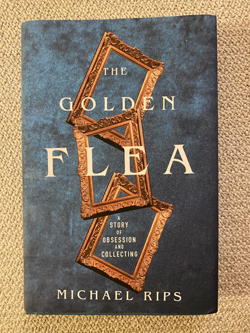

The Face of the Naked Lady: An Omaha Family History appeared in 2005 and disinters a painting by his father. The Amazon reviews are a hoot. Naturally I welcomed the arrival this spring of The Golden Flea, A Story of Obsession and Collecting (New York: W.W. Norton, 2020, 202 pages, $26.95)

The author attended Princeton University, Oxford University, and received his law degree from George Washington University Law School. He also clerked for Supreme Court Justice William Brennan. Among his clients were artists and art galleries. Since 2017 he has been the Executive Director of the Arts Students League. The author and his wife have lived in the Chelsea Hotel for over 20 years. The book is dedicated to Sheila and their daughter Nicolaïa.

On a visit to New York with my son Noah in 1999 to present a jointly authored paper “Children’s Memories and Literature – before, during and after Shoah,” at the 29th Annual Scholar’s Conference on the Holocaust, at Nassau Community College, we also enjoyed jazz at the Blue Note and purchased at the Art Students League a sweet 4×6 oil of three people at a grand piano.

Second hand, previously owned, used, thrift shops, pawn shops, jumble sales, flea markets in town squares, drive in theaters, garage, yard, estate sales, echo hand me downs and bargains. These are off-beat venues for finding artifacts of querulous value. Everything is a bargain without provenance and rarely a back story. Sleepers are charming; we found a nicely framed oil of Venice at a thrift shop on Pico Boulevard in 1967 for 25 cents. Street artists cranked out thousands of Venice views for tourists. We still have not been to Venice, our beloved picture, restored, hangs in our guest bedroom. Michael liked picture frames which he framed with larger frames. Sometimes professional framing is more expensive than the picture.

The twentieth century London antiquarian book trade was fed by scouts and runners who ferreted books from unlikely places for dealers. Every so often you make a find. A book signed by the author, inscribed to a friend, with a bookplate; these association copies establish provenance and enhance value. In art provenance and authenticity are vital, forgery and fraud are a plague. Art dealers, museum curators, the establishment tend to look askance at amateurs bringing their finds for appraisal, Antique Roadshow notwithstanding.

Rips spent over two decades at the Flea. Dealers, pickers, and vendors had colorful names, backgrounds and vignettes — Jokkho, the Dane, the Diops, the Prophet, the Cowboy, Kervorkian and the more normative, Paul, Frank, Bobby, Mike, Morris, Sophia, and Ethel, the latter being a specialist in Judaica, especially Menorahs, who started as a man and transformed into a woman. The author is the standout character.

A compulsion to collect fed by an abundance of a curious cornucopia of reasonably priced artifacts existed less that ten minutes away. There was little restraint to curtail the obsession. Renting of storage units circumvented the limits of wall, floor and mantle space in the home.

The subtitle of the book, “Obsession and Collecting,” has been a subject of discussion in my house for over 40 years. Concerns about accumulation, saving, curating, storing, not throwing away, and hoarding are discussed frequently. I have contemplated a Museum of Detritus for about a decade. The dozens of quotidian categories include grooming with four generations of nail clippers, nail files, tweezers, little brushes, shoe horns, and old eyeglasses. My library includes about a dozen books on stuff, how to organize and dispose of it, including Compulsive Hording and the Meaning of Things by Randy O. Frost and Gail Skeketee (2011), and The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up (2011) by Mari Kondo.

The author searched his perhaps addictive collection habits. “What I needed was a therapist to explain how I had become so ridiculous. Ridiculous because I had allowed myself to be seduced by my own conceits of the flea.” The process “was as near to a numinous experience as one can hope.” Michael and Sheila had a party in their home, a veritable gallery. Michael, humiliated by a guest who called him a hoarder took action and declared, “I could not have felt better, cleaner, thinner. It was the great vastation. I was determined to stop going to the flea.” The author challenged the reader’s vocabulary. I knew what numinous meant, but googled “vastation,” which means forcefully emptying or purifying.

Despite the temptation of the Flea being a 9-minute walk, a 3-minute bike ride from home in the Chelsea Hotel, Michael went cold turkey on the Flea for a year. But to the benefit of the art world Rips was a recidivist.

Something about the dusty portrait, “Francis,” in a dealer’s basement intrigued the author. The dealer said, take it home, see how it fits. The house was full, Michael left it there. Later, still in the basement, he appropriated it. Fifteen years searching for evidence ended in a “rapturous transport.” Francis was the name of the artist not the depicted subject. The subject was the nurse who encouraged a convalescing serviceman, her patient to paint, and then married him. The portrait did not resemble the later work identified with the famous Sam Francis. The author’s written description is alluring; readers would benefit from a picture of Francis’s early work.

After about 40 years the Chelsea Flea closed in 2019. It had declined from twelve hundred to fifty vendors. The author studied philosophy particularly the French philosopher of Lithuanian heritage, Emmanuel Levinas. The Golden Flea appeared in Spring 2020. It went to press before COVID19. This paragraph that transcends the Flea and may contain existential meaning – “The destruction of the garage was an expression of our failure to protect and nurture uncertainty, the mutating salvation which resides within and about us. Whether uncertainty has an existence outside our thoughts or is a category of consciousness, it is fixed to our being, and as such, it responds to, reacts against, historical forces.” The are some online reports of the Flea’s resuscitation, though COVID19 may have interfered.

In an April 23, 2020 Martha Stewart zoom interviewed her friend Michael Rips for Midtown Scholar Bookstore in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Stewart in her celebrity endorsement declared the The Golden Flea as “delightful and delicious.” The interview is available on YouTube.

*

Oliver B. Pollak, Ph.D., J.D., a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com