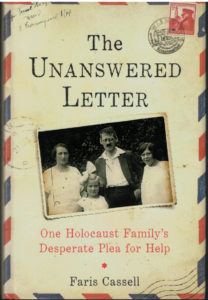

The Unanswered Letter: One Holocaust Family’s Desperate Plea for Help by Faris Cassell; Regnery History (c) 2020; ISBN 9781684-510177; 437 pages including acknowledgments; $29.99

SAN DIEGO — This history of one Holocaust family’s experiences, together with a book by Julie Gray that I reviewed yesterday — The True Adventures of Gidon Lev in in which Gray traveled with Lev to the major venues in his life — leave me with a hopeful sense that we are moving into a new era of Holocaust research and scholarship. I’m hopeful because I’ve often heard Holocaust survivors ask plaintively, “When we’re gone, who will tell our stories?” The answer is that an entirely new generation of journalists, descendants, and academics will probe the history of the mass murder of six million Jews, unearthing untold stories and bringing to them fresh new perspectives. I believe this should be seen as a welcome development that supplements the many fine first-person accounts we have from a diminishing cadre of Holocaust survivors. It’s possible that The Unanswered Letter, which brings a far more global perspective to the Holocaust than do most survivors’ memoirs, will typify the new scholarship, moving easily between personal stories of families caught in the Holocaust to the historic forces and personalities that combined to create the hard, cruel, unmatched tragedy.

SAN DIEGO — This history of one Holocaust family’s experiences, together with a book by Julie Gray that I reviewed yesterday — The True Adventures of Gidon Lev in in which Gray traveled with Lev to the major venues in his life — leave me with a hopeful sense that we are moving into a new era of Holocaust research and scholarship. I’m hopeful because I’ve often heard Holocaust survivors ask plaintively, “When we’re gone, who will tell our stories?” The answer is that an entirely new generation of journalists, descendants, and academics will probe the history of the mass murder of six million Jews, unearthing untold stories and bringing to them fresh new perspectives. I believe this should be seen as a welcome development that supplements the many fine first-person accounts we have from a diminishing cadre of Holocaust survivors. It’s possible that The Unanswered Letter, which brings a far more global perspective to the Holocaust than do most survivors’ memoirs, will typify the new scholarship, moving easily between personal stories of families caught in the Holocaust to the historic forces and personalities that combined to create the hard, cruel, unmatched tragedy.

The Unanswered Letter begins when author Faris Cassell, a Christian, is shown a letter by her Jewish husband, Sidney, that was given to him by an elderly descendant of an American Christian family. It was a plea for help from Alfred Berger on his behalf and that of his wife, Hedwig, a Jewish couple trapped in Nazi Austria, to a Mrs. Clarence Berger of Los Angeles, whom he hoped might be a distant relative. “The only possibility to join our children, the dearest we have in this world, is the way to America and I beg you instantly to send us/ for me and my wife/ an affidavit,” the letter said in part. “Our children are young and laborious with a good profession/ my daughter is a music teacher and her husband is a tailor/ and surely they will soon earn their living in order to take care of us too. Besides we have enough energy to earn our living ourthelves [sic]. Therefore you could not have the least trouble with us.”

The Bergers who received this letter were not Jews; they were Christians of German heritage. An affidavit would require them to pledge to support the Austrian Bergers, so they would not be a burden on American society — a very big ask, perhaps too great for whatever financial resources the American Bergers had at their disposal. Whatever the reason, they did not respond to the letter, but nevertheless they kept the written plea, which was found many years later by their elderly niece, Margaret. Perhaps because Sidney was the only Jew she knew, Margaret gave him the letter. He in turn showed it to his wife, Faris Cassell, a journalist. Intrigued, she decided to follow up on the letter, make a few inquiries and perhaps write a feature story. Instead, the more she dug, the more involved with the story she became. As readers, we get to follow the course of her research, her breakthrough when she made contact with a granddaughter of Alfred and Helwig; and the subsequent involvement of other members of the Berger family in a search for the truth about how Alfred and Hedwig died. En route, we readers also learn the other family members’ stories, which could not have been understood without also knowing about government actions and policies of the Germans, British, Americans, the French, Spaniards, Czechs, Turks, and Cubans among others, who either facilitated or blocked the Bergers’ desperate search for refuge.

Eventually, author Cassell traveled with a group of the Bergers to Vienna, Austria, to see and mentally absorb the places where Alfred and Helwig lived; to conduct interviewsl and to do archival research. In this, The Unanswered Letter shares a commonality with The True Adventures of Gidon Lev; both authors needed to see the key places where their subjects lived; they needed to walk the same streets, step inside the same buildings; experience the same seasons; taste the same foods, and breathe the same air to gain deeper insights, so their accounts would not simply be verbal, but also introspective and emotional.

Cassell and Gray shared another commonality: they both with great persistence asked themselves what would they have done in the same circumstances? What if they had been Jews living in the tightening noose of Nazi restrictions? What if they had been non-Jewish neighbors, threatened with severe punishments, up to and including death, if they helped any Jew? For Cassell, this required examination of the beliefs she had grown up with in her comfortable, affluent, white Protestant neighborhood. For Sidney, it meant confronting a family history — the loss of his own relatives in the Holocaust — that he had locked away in a rarely opened compartment of his brain.

This book is comprehensive and so well researched that, no doubt, it will win plaudits from history professors. On the other hand, it is so personal, and compelling, that it’s likely to appeal as well to a general audience.

Assuming other authors are likely to follow suit, the combination of these two attributes will help to assure that the memory of the Holocaust will be kept alive.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com