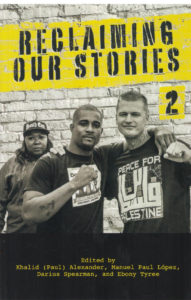

Reclaiming Our Stories 2 edited by Khalid (Paul) Alexander; Manuel Paul Lopez; Darius Spearman, and Ebony Tyree; San Diego City Works Press; © 2020; 170 pages with additional resources and study questions; $15.95.

SAN DIEGO – In my continuing quest to learn the stories of other peoples – in what you might call independent ethnic studies for a Jewish septuagenarian—I picked up this book and was intrigued by one of the fellows pictured on the cover. He was wearing a shirt with the slogan, “Peace for Palestine.” I wondered what kind of peace he had in mind.

SAN DIEGO – In my continuing quest to learn the stories of other peoples – in what you might call independent ethnic studies for a Jewish septuagenarian—I picked up this book and was intrigued by one of the fellows pictured on the cover. He was wearing a shirt with the slogan, “Peace for Palestine.” I wondered what kind of peace he had in mind.

However, as it turned out, his shirt had nothing to do with the 19 stories that were presented in this slim volume – each story typically three or four pages, writing exercises by people who had suffered setbacks in their lives. Whether writing about their problems were really instances of “reclaiming our stories” or simply good, cathartic therapy, I am not qualified to say. What I can say, however, is that this is an emotional book, with points of view which I, as a middle class Jewish grandfather, had not been deeply conversant.

Three of the short stories dealt with life in prison; four with sex abuse, exploitation, or trafficking; three with various kinds of racism; five with debilitating illnesses; and others about such diverse topics as domestic violence, foster parents, juvenile gangs, and child abuse.

As you might imagine, I was on the lookout for any Jewish references, but I found only two. In discussing her recovery from breast cancer, author Romelia “Meme” Turner spoke positively about the treatment she had received from a Dr. Goldstein, her oncologist, who presumably was Jewish. On the other hand, David Grant, who wrote about his drug arrest, was critical of the Polinsky Center, to which he and three siblings long previously had been as youngsters because their parents were drug addicts and in an abusive relationship. The county-operated Polinsky Center was largely financed with a gift from Jessie Polinsky in memory of her husband, A. B. Polinsky, who once had owned the Coca-Cola Bottling Company in San Diego.

Grant did not know of the husband and wife philanthropists; in fact he misspelled the name of the center as “Polanski.” But he remembered his stay there as “the first time I experienced institutionalization. This facility honestly felt like baby jail. … I can distinctly remember we weren’t able to move freely around the facility. Yup, this was the first time I experienced confinement. There was something unusual about being a child with the inability to move about freely; unable to run outside, no freedom to express myself, and often punished for no reason.”

Surely, what Grant described was not what the philanthropist Jessie Polinsky had envisioned when she contributed $5 million to assure construction of a 6-acre campus to replace the old, crowded Hillcrest Receiving Home.

The story with the most provocative title was “I Hate White People” by James L. Smith II. He went on to say he didn’t hate people who were white, only those who practiced the many forms of racial discrimination that he had encountered in his life. In his view, “the term ‘white supremacist’ is redundant. Anyone who calls himself ‘white’ alone is a declaration of supremacy. Anyone who calls himself ‘white’ as a race, dons the cloak of the privileged oppressor.” There’s much to think about in those declarations; in my gut, I feel that this is too facile a formulation.

One story which, in particular, aroused my sense of empathy was told by Asma Abdi, a Somali woman who remembered her school teacher’s Islamophobia. Although her name was “Asma,” the teacher thought himself clever calling her “Osama,” a reference, of course, to the terrorist Osama bin Laden. Then the teacher said he didn’t mean to call her “Osama,” he meant to call her “Asthma,” another joke at her expense.

She wrote: “I felt very offended. In the Quran, my name means high, exalted, great, but in that moment, I had never felt so low.”

The teacher had served in the U.S. military in Iraq, and one day, telling his wartime experiences , he walked over to Abdi and said that women of the Middle East (although she was from the Horn of Africa) “aren’t allowed to learn, go out, or do anything without approval or permission…I could come up to her and rape her without warning, and she wouldn’t be able to do anything about it. “

Abdi recalled that she “sat there stifled, nobody said a word. I swallowed my voice, my eyes began to well up with tears, and I ran out of the classroom.”

It’s hard to believe that we have high school teachers like that in San Diego County, who purposely humiliate their students. They ought to be fired, but when Abdi and her family finally were persuaded by friends to file a complaint, the school took no action. Then, she said, an attorney for the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) threatened a lawsuit, prompting the school to require the teacher attend mandatory sensitivity training classes.

Among many of my fellow Jews, CAIR is a controversial organization, which they say has ties to anti-Israel terrorists. I have no independent knowledge of this, but I do believe that in the case of Asma Abdi, CAIR’s advocacy was a mitzvah.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com