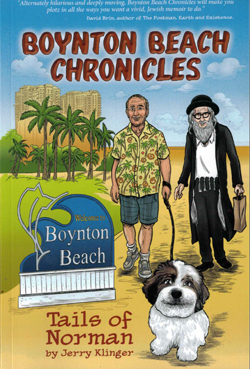

Editor’s Note: The following story, divided into three parts, is republished, with permission from author Jerry Klinger, from Boynton Beach Chronicles: Tails of Norman. It will run today, tomorrow night (after Shabbat), and on Sunday.

-First of three parts-

BOYNTON BEACH, Florida — I’m not sure what prompted me to talk to him. Obviously, no one else did. There was this strange apparition, something out of hundreds of years ago from Jewry’s European past, sitting in the Starbucks on Congress Avenue next to the Vitamins R’ Us Super Store.

BOYNTON BEACH, Florida — I’m not sure what prompted me to talk to him. Obviously, no one else did. There was this strange apparition, something out of hundreds of years ago from Jewry’s European past, sitting in the Starbucks on Congress Avenue next to the Vitamins R’ Us Super Store.

I had stopped off for a Mocha Java Grande with extra mocha and cinnamon. To be sure to stick to my diet, I threw in two Nutra-sweets. He was sipping a glass of water from a plastic cup at a corner table. Sweat visibly thickened through his white, long-sleeve shirt buttoned at the collar. He had a long black coat, a bit dirty and frayed at the hem, that touched the floor. His oversized black-felt hat, with the extra-large, firm brim, lay on the table. His full grey-flecked beard wiggled whenever his hand nervously readjusted his black yarmulke. Mendel’s large gentle eyes cried his tired confusion. He was out of his element. It was 82 degrees outside, very bright and humid.

The last winter in Crown Heights had been too much for Mendel, the snow, the ice, the cold, the terrible pain of his arthritis, the oy- vey’s-mir days. For 44 years, he had lived just off Brooklyn Avenue in a small third-floor walk-up apartment that overlooked a grey alleyway. There never was much sunlight. It was affordable.

The two Pothos plants on his windowsill did okay. They were his family since he was never married. He named them Chaim and Shana. Mendel borchered (complained) about his landlord. “He never turns on the heat until November 15th; not one day sooner or later, and the hot water – forget about it.” As much as he complained, he complained so that his landlord never would hear him. Another rent-controlled apartment at $147.50 a month was impossible to find.

As the years advanced, so did his arthritis. The swelling in his joints got worse, but for $147.50, he suffered to himself. This winter it took him a long, long time to climb the steps to his home. He even stopped going to the Crown Heights, Brooklyn Public Library because the extra flight of steps was excruciatingly painful to climb. He missed the library. Except for the little bit of study he did at the yeshiva, the books at the library were his only friends, other than Chaim and Shana.

Mendel made his living as as a shames (caretaker) at the Torah Ohr shul three blocks over. It was a small building with two front doors and one large common stoop. The door to the right opened to Torah Ohr. The one to the left opened to the First Abyssinian Church of the Holy Redeemer. The arrangement worked well as both communities were small and got along well. Mendel worked as the shames for the shul and looked after the church. He swept. He cleaned. He straightened. He watched to be sure that everything was where it should be so each could worship God. It made him feel good. He was content. He loved God in his own quiet non- flamboyant way. Anything that brought people to God was okay with Mendel.

Mendel was a Chasid. While working at Torah Ohr and the First Abyssinian Church of the Holy Redeemer, he attended the Beth Dovid Chasidishe Shul on Empire Boulevard next to the Chicken and Chitlin Palace. He liked the people at Torah Ohr. He liked most everyone. Just because he liked the people, it did not mean he worshiped with them.

He preferred Beth Dovid. Mendel could sit quietly on Shabbos on the backbench near the window and dream or shuckel (bend back and forth in prayer), depending on his mood.

No one bothered him. He bothered no one. He was never offended even when there were schnapps after Shabbos services and sometimes, they ran out just before it was his turn for a pour of L’Chaim. It was okay. It was the arthritis that made his life so difficult now. The cold made his life impossible with pain.

Beth Dovid’s Rebbe’s eyes followed Mendel as he took his usual seat by the window. It was quite clear he was suffering. The Rebbe asked an aide to have Mendel see him in the afternoon. Rabbi Fuchs was a kind man and only wanted well for his flock. It troubled him personally to see a Chasid in any sort of difficulty. It pained him so much he could not stand to see it. Mendel did not want to cause any pain for Rabbi Fuchs.

After services, Mendel did as he was asked. He sat with Rabbi Fuchs. He sat and they talked behind closed doors in the rabbi’s office. Actually, Mendel sat. Rabbi Fuchs talked. An hour, maybe more, Mendel emerged, grimacing this time from more than the arthritis.

Rabbi Fuchs told Mendel that it was a sacrilege to spend the remaining years of his life in pain in the cold and wet of Brooklyn. God created a special Jewish haven for those whom the cold had cursed, Florida. Rabbi Fuchs went even further: his nephew Naphtali had researched Florida. He discovered the second fastest-growing Jewish community in America was Boynton Beach where there were almost more Jews than in Crown Heights. “Mendel,” he instructed, “go to Boynton Beach, your life will be better there. God has told me you should go.”

*

Swirling my Mocha Java Grande with extra mocha and cinnamon, one eye glued on the brown wooden swizzle stick for splinters, I did something I haven’t done for decades. Boldly I walked up to the apparition and said, “Hi, my name is William Rabinowitz. You look like you are lost. Can I be of assistance?” The hand went to the yarmulke, adjusting it in a circular motion. The beard twitched. His face sought mine.

“Thank you for asking. I am not sure where to go tonight. The Rebbe sent me to Boynton to a friend of his. He recommended I go to the Days Inn. Is it a long walk from here? I have been walking a long time today. My name is Menachem Mendel Meyers. But Mendel is fine,” he said.

It was then that I noticed his large suitcase under the table. “It is a long walk from here,” I said.

“Is it very far?” Mendel asked. “Well, I would not recommend walking it and schlepping a heavy suitcase in this heat. It is at least another mile and a half east across 95,” I responded.

The hand went to the yarmulke and nervously readjusted it one, then two more times. Mendel turned his head and looked out the window at the traffic flowing up and down Boynton Beach Boulevard. The sun shone brightly on the street, muted by the tinted window glass making it seem cooler than it really was. One of his long, round peyot that was draped behind his ear slipped forward and dangled. He quickly, with a twist of the long earlock, pushed it back up behind his ear again.

I’m not certain I understood what happened next. Mendel seemed to sense a connection, him and me. He began telling me about himself. I thought of myself as a total stranger to Mendel. He did not feel I was a stranger to him. He did not feel the need to keep secrets. He wanted me to know him. It was so strange.

“Tell me, Mr. Rabinowitz, is there a kosher restaurant or a grocery store nearby? I did not think ahead, being as I was told Boynton Beach is a very Jewish area, I thought I would be able to find something to eat easily here.”

“You know Mr. Rabinowitz, As a child, my mother had sent me to a yeshiva in my hometown. My father was absolutely against an Orthodox education. “God did not listen anyway” he said. “It was a waste of time.” But on Yom Kippur he would go to shul. My mother, a Holocaust survivor, was from the old school, felt I needed a Jewish education based on study of Torah and Talmud and Yiddishkeit.

After my father died, there was no argument. My mother sent me to the Hebrew Academy – half a day in Torah studies conducted in Hebrew and half a day in regular American subjects – the three Rs taught in English.”

“I too had to go to the synagogue Hebrew school,” I told Mendel.

“I was, without a doubt, one of the poorest products they ever put out,” I quipped.

Mendel looked into my face. “I might disagree with that,” he said. “Something of the meaning of being Jewish became part of your bones.”

I always kept that part of me private, buried. Mendel had seen what I kept hidden. I understood Mendel and respected his values, though I did not actively share them. He was hungry and he did not know where he could go to get a little food without violating his living link to God and to his people. It had only been a few minutes, but a kesher, a bond, had been formed.

“There is a Publix grocery store kitty-cornered to us on the other side of Congress,” I said. “You could buy some fruit there.” I felt guilty saying this. Mendel had something about him that was very non- threatening. He was not asking for anything except where he could get some food and how could he find a place to rest.

Here was a Jew in need. I sat there with my Mocha Java Grande with extra mocha and cinnamon and a double helping of Nutra-sweet.

Mendel had finished the water in his plastic cup. Something would not let me just get up and go. Something inside would not let me abandon a person in trouble when human contact has been made.

“Mendel, you know I have not had any lunch yet and could use a bite. There is a Kosher restaurant a ways from here on 441. It is called Ben’s,” I suggested.

His face lit up a bit. “Ben’s, of New York?” he asked.

“Yes, the one and the same, complete with a hechsher from the Vaad HaRabbanim of Palm Beach County. The rabbis and Ben’s have certified that it is not just kosher but glatt Kosher. The certificate sits in their front window. You can read it yourself. It has the best corn beef sandwiches on fresh thick rye bread this side of New York!”

Whether it was the best corn beef sandwiches or not was my exaggeration. What was not an exaggeration was that it was the only place for five miles that Mendel would be able to sit like a dignified human being, have a good sandwich, and have his religious values respected.

“Would you like to join me? The wife is playing mahjong this afternoon and I have no company for lunch. We can go to Ben’s and I will take you to the Days Inn afterwards,” I told him.

It was as if the bright sunlight of the Boynton Beach day suddenly illuminated the table in a warm white glow. It felt very good. What he said next was quite unexpected.

“Martin Luther king Junior said, ‘Life’s most persistent and urgent question is: What are you doing for others?’ Thank you for being so sensitive.” He reached across the table and touched my hand as he said this.

I never would have expected a Chasid, who looked like he came from an isolated 18th century Polish village, to have even been aware of Dr. King.

Mendel changed how I lived in the world. I’ve only known him for two years and a few months. He’s made me see. He’s made me laugh at times to the point of tears. He was an extraordinary gift. There are many stories I can share about Mendel. Perhaps I will later. One of the first things he taught me was the value of self-respect and dignity.

*

Mendel was squared away in Boynton within a few days. The wife and I helped him find a small rental in Starlight Cove, about a 15-minute walk to the Chabad Center. It had a postage stamp patio viewing the small lake bordered by the seventh hole of the adjacent Westchester Country Club golf course. Golfers would express themselves in truly creative ways whenever their shot landed in the water hazard instead. Mendel never seemed to take offense.

After one particularly colorful display of temper and bad language that we witnessed together, a frustrated red-faced old geezer, wheezing, threw his club into the lake. He missed the dog leg landing area from the tee. I thought Mendel did not hear his outburst, but he did.

Lifting his face back up to bask in the warmth of the sun, Mendel said quietly, “‘Better to do something imperfectly than to do nothing flawlessly.’ Robert Schuller, the great American evangelist, said that once William. He focused in his teachings toward positive aspects. Rather than concentrating on condemning people for sin, he encourages Christians (and non-Christians) to achieve great things through God and positive thinking.”

I looked up into the warmth of the blue sky and said nothing. I did not know what to say.

Mendel was not a wealthy man. He needed to find a job to help pay his way. Shames jobs, synagogue custodian jobs, in Boynton Beach are hard to come by. The Chabad center had no need for Mendel’s skills, even the book straightening up was done by volunteers gaining Brownie points with God as they passed time in his waiting room. Almost all of the synagogue communities in Boynton were Reform temples. Almost all of them used Ortega’s Building Engineering Services Inc. for shames work. Ortega provided largely undocumented, non-English-speaking crews. The Temples had no job for Mendel.

“I don’t want charity. I want the opportunity to work, to make my own dignity, and not be dependent upon others for it,” he told me.

“The Rambam, Moses Maimonides, wrote about charity and human dignity a thousand years ago,” he added. “The lowest form of charity is giving money to the poor to make them go away. The highest form of human charity is to give people a job so they can take care of themselves. A human with dignity can and will help others. We all can work to make this world a little better than when we first arrived. “

Walmart balked at the Chasidic Jew with the beard, black hat, long coat, and dangling ear-locks asking for a job as a door greeter. We thought of service jobs such as Dunkin Donuts. After all, they do sell bagels. Mendel applied, but we both knew he would be rejected.

“Picture this,” he said, laughing. “I walked in and asked the manager about a job. He’s a nice young man. Jason is his name according to the picture on the wall. I think I scared him. His jaw could not move as he handed me an application. You will have to wear a beard net, a hairnet, a special cover for those dangly things on the side of your head, the words came out. We don’t allow hats, and … and… ”

By this time, Mendel and I were both rolling with laughter and gripping our sides. Mendel did not get the job.

“Churchill said during the darkest hours of the Battle of Britain, ‘Never, never, never give up.’” Mendel reminded me.

I chimed in, “My great concern is not whether you have failed, but whether you are content with your failure ~ Abraham Lincoln.”

We continued searching together. For a while, I thought about setting Mendel up in a little business at the biggest flea market in all of south Florida – Sample Road. We hopped into my Chrysler convertible Sebring with the top down. Mendel sat with one hand holding his yarmulke down on his head so it would not blow away, his broad-brimmed black hat in his lap. With a grin on both our faces, we took off for Sample Road. Mendel had no experience in retail. He did not know a balance sheet from a seesaw. Most people have no idea what a balance sheet is either except at the doctor’s when you get on a scale and they balance how overweight you are.

It must have been beshert – meant to be. I usually had my Sun Pass on my windshield to breeze me through the electronic tollbooth at the entrance to the Florida Turnpike to go to Sample Road. My Sun Pass had been stolen. Maybe it was borrowed by a poor person on a fixed income who could not afford to pay the tolls on the Turnpike, I tried to reason. But no, it was simply stolen.

We stopped at the pay cash and receipts part of the tollbooth entrance. As I handed my dollar to the tollbooth operator in the bright yellow, green, and brown Hawaiian shirt, I saw the sign. Tollbooth operators wanted.

“Mendel, what do you think?” I looked over to my friend. His hand had already gone to his yarmulke, twisting it three times to be sure it was okay. “Why not?” he responded. Being handed back my change, I asked the operator where I can get an application for a job.

“Have one right here,” she said. “If you should decide to work for the Turnpike, be sure and mention my name on the application. I can get $25.00 if you do. My name is Lucy Centinelli. That is spelled C-e- n-t-i-n-e-l-l-i ,” she said slowly. There were already six cars backed up behind us. We thanked Ms. Centinelli and exited the turnpike at the next opportunity. We headed back down Atlantic to Jog Road to my home. Mendel was excited. So was I.

Sitting at the kitchen table, I filled Mendel’s personal glass cup with boiling water. He kept a small set of glass dishes and cups at our home. We kept everything separate from our own as we did not follow the level of observance he did. It wasn’t that he was saying he was better than us. We instead were saying to him, we respect your values. A tea bag of Swee-Touch-Nee tea, a lump of sugar and we sat down to peruse the application and the job description.

(End Part One)

*

Jerry Klinger, founding president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, enjoys writing fiction in his spare time.

Pingback: Fiction: Mendel the Chasid's job interview - San Diego Jewish World

I never read fiction. Except yours! And that’s the truth. I am eager for the next installments.

Pingback: Fiction: Mendel the Chasid applies for a tollbooth job - San Diego Jewish World