BOYNTON BEACH, Florida — My mother was never a pacifist, at least I do not remember her ever having taught me a code of values that suggested so. She never spoke of the right to fight or even worse to kill. Yet she did teach me much about the value of life, the meaning of hate, and forgiveness. She taught me even when I thought I was not listening.

My parents were Holocaust Survivors. They were not survivors who adorned the tragic mantel of victimhood. They were not among the fortunate few to find a safe haven in the U.S. or elsewhere before Hitler had arrived on their doorsteps.

My father, Fritz, was born in Vienna, Austria. He was liberated from Buchenwald by General Patton’s forces.

My mother, Rita, was born in Lodz, Poland. She was liberated from Bergen Belsen by the British Army,

My parents survived the Nazi Concentration Camps. If the armed might of military force had not arrived when it did, they would have perished in a matter of a few more weeks.

Though liberated, they were never fully liberated from their mental and physical trauma.

My father died nine years after his liberation from the effects of having been a Jewish slave labor sold to the Vichy French. When he could not work enough, the French gave him back to the Germans for a Final Solution.

My mother lived to be in her late eighties. Physically she was robust to the end. Mentally, she spent the rest of her life moving in and out of paranoid schizophrenia and warehoused institutionalizations.

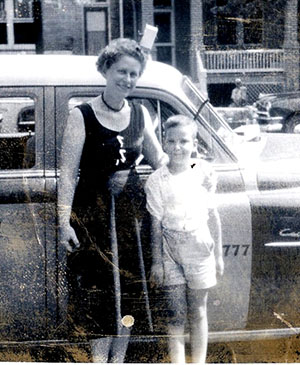

For years she attempted to stabilize her life and raise me alone. Her personal dysfunctional trauma had its effect. Between the periods of darkness, which created enormous home tensions for me growing up, she did her best to mother, to mentor, and to teach.

At holiday dinners, she, and her surviving sister, frequently spoke of their shared experiences from the Camps. For us kids, all we could do was listen with mouths agape.

She never spoke of vengeance. She never spoke of hate. She never spoke of wishing God would bring a terrible sword of retribution on anyone.

It was a contradiction of emotions for a child who could see his mother had been hurt, and yet she did not want to hurt anyone back. I wanted to protect her when I could not. It resulted in teenage rebellion, tension, and anger between my mother and me.

Like most growing up in the 60s, a period of idealistic human and civil rights activism, I wanted better for everyone. Marching against the Vietnam War, marching on picket lines opposite KKK members in full regalia, was my high school world.

It was not unusual for me to speak of Peace, love, and understanding to her. Even if underneath, I was feeling a pain that manifested itself in deep conflict and resentment.

One evening, we were standing in the kitchen. I was off on an idealistic rant, demanding of her, “why can’t people get along. Can’t they just live peacefully together? Can’t people just turn the other cheek? Why do people have to fight?

Without a moment’s hesitation, my mother, who had been standing in front of me listening to what I said, suddenly slapped me across the face, hard.

Instantly, I was in a rage of response. Anger came up from deep inside. I was afire with desire to respond, but contained myself smashing my fist into the refrigerator, knocking it back.

My mother calmly looked at me and said, “That is why people fight”. She calmly turned and walked away.

The lesson took instantly. I understood, though I was still fuming with anger, what she was saying. People fight, when innocently and for no recognizable wrong, are attacked by someone they are angry with.

I fumed. I learned.

In our apartment building, there was a common area for the mailboxes. My mother and I were picking up the mail when she stopped to talk in Polish to a young Polish diplomat who lived in the building. They were friendly. He was courteous.

I was confused.

Upstairs, I asked her why was she civil to the Pole? “The Poles had gone out of their way to torment you and help kill our family and so many others,” I said. I heard you and Aunt telling so many stories about the War.

My mother took the opportunity to mother and teach again.

She said, “Why should I hate him? He never did anything to me. He was much too young to have ever done anything.

At most, he was an innocent child himself.

His father, his family, I might have reason to resent them but the young man, he is innocent.”

My mother taught me about the transmission of hate. The sins of the father are not the sins of the child. A person can and should be judged on what they have done and not what others did, even in their own house.

How we comport ourselves in life is what we should be judged for. Poles, not all Poles, but those who did wrong or evil, should be singled out. Poles, or any people, who have never done wrong, should never be group punished for the sins of a few bad people amongst them or for their dark history.

The Holocaust was a time of unbelievable evil, human beings killing other human beings because they hated them. They killed not for something they had done or did to others, but because hate was given freedom to hate.

Yet it also was a time when to save life, killing life, was absolutely, essential.

My wife’s cousin is a Black Hat in Jerusalem, an extremely orthodox, conservative Rabbi. He runs a Yeshivah, a fundamentalist Jewish school dedicated to the study of Jewish laws and the bible. Periodically, he came to the States to raise money for his Yeshivah.

We met him in Baltimore one evening for dinner.

It was clear he was agitated. Seething might be a better description.

“What is wrong?” my wife asked him.

He stewed for a minute and answered bitterly. “I was turned down for help today from a wealthy man because he only wanted his money to go to support his local abortion clinic.”

“What a Mamzer (bastard),” he spit out the word. “All abortionists are monsters, murderers, they should rot in Hell forever,” he gesticulated with his finger jabbing the air.

I sat quietly and looked over at the bearded angry Rabbi.

“My uncle was an abortionist,” I said.

The Rabbis face contorted in disgust. He seemed to be spitting with pure hate.

I continued.

“During the War, my uncle was a doctor, an abortionist who aborted every Jewish girl he could,” I said. “I heard stories about him from my mother.”

The Rabbis face reddened with rage. I continued.

“In the Nazi world, in the camps, if a Jewish girl was discovered to be pregnant, she was killed immediately. My uncle’s secret job was to save life by killing life. Should his soul go to Hell and rot forever?” I asked.

The Rabbi choked noticeably on his own tongue.

“A time when death was life and life was death,” I said.

The dinner ended quietly.

My mother’s last days were in an institution. When I visited, she warned me, “beware the white powder. The Germans have not finished their job.”

We thought she was insane and let it go as Holocaust trauma. It turned out she was not insane.

We learned after her passing that the Nazis of Bergen Belsen were storing food to be given to the surviving inmates. The food was covered with a white powder. It was a deadly poison. They intended to finish the job before liberation.

To the extent she could, my mother tried to teach me about a better world while she teetered between trauma and madness.

I never claimed to be a pacifist. I cannot claim to be a conscientious objector, though I personally admire those who are.

What I can claim with pride is that I was taught to respect life and to measure each human being on who they are and what have they done.

To others, my mother was a tragic victim of evil. To me, she was a courageous woman who, even at the end, wanted to speak of life.

*

Jerry Klinger is the President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. www.JASHP.org.

Dear Mr. Klinger,

I was so moved by your story and your attitude about life. What a great lesson! Also, thanks, Debbie, for letting us know about the contributions that Jerry Klinger has given to Israel and our people.

You, yourself are so humble. Most people do not realize what you have done for Israel’ and the Jewish people. Your accomplishments can teach future generations what it means to give of yourself

This would make a great sabbath sermon