By Sam Ben-Meir

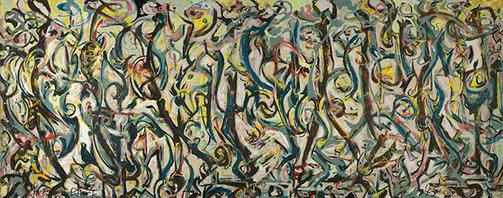

NEW YORK — Since at least 2014, Mural (1943) has been on perpetual tour. So much has already been said about this large painting – books are devoted solely to the analysis of Jackson Pollock’s first great masterpiece. What else can possibly be said? In fact, there will always be new things to say. As with any work of genius, it exceeds every interpretation. Mural is generally regarded as a transitional work – between the mythological, Jungian abstractions and the later drip paintings which would secure Pollock’s world fame.

Pollock is determined to paint as though no one has ever painted before – as if he was the first to ever pick up a brush. Pollock wants to rediscover the universe entirely within himself: the truth lies within. “I am nature,” Pollock would declare. The greatness of Mural is precisely that it stands entirely on its own – Pollock finds within himself the resources for a new universality. “The modern artist,” he would say “… is working and expressing an inner world – in other words – expressing the energy, the motion, and other inner forces.”

One of Immanuel Kant’s most insightful observations about art and what distinguishes the genius of the artist from the most brilliant and original of scientific discoverers is that the work of artistic genius is inexhaustible. Here are a handful of ways that Mural may be interpreted.

Mural is Pollock’s first true response to the totality of western painting. Mural is a full engagement with the history of painting. Going back to the paintings of Lascaux – from the beginning, painting is about attaining a mastery of the world. This is what Pollock is doing – but it is more about penetrating and unfolding the artist’s unconscious than about mastering the external world and its megafauna. It is the culmination and supersession of everything that has come before. It is Pollock’s Aufhebung of easel painting – that is, his suspension in the dual and opposed senses of the term: to at once abolish and preserve.

Pollock was immensely and directly influenced by the great Mexican muralists. For Los Tres Grandes painting was a source of liberation, art as a form of protest. With Mural, Pollock retains the emancipatory potential – but social-political liberation interests him less than freeing his unconscious. Painting is emancipatory inasmuch as it subverts our ordinary ways of seeing; inasmuch as it enables us to see in new ways.

The painting may also be seen through a metaphysical lens – where it becomes both a non-hierarchical and essentially monistic vision of reality and a kind of critique of our claims to knowledge of reality. The painting functions masterfully as a critical appraisal of its own conditions of possibility. On the one hand, Pollock’s painting, his use of paint, functions as an interrogation of being. Pollock is, however, also well aware that we are afforded no access to being that is not mediated by our subjectivity, and particularly our unconscious. What is remarkable about Mural is its implicit faith that the unconscious does not merely filter and impede our access to reality but indeed provides the only true avenue to being. It is through the unconscious that we participate with reality at the deepest level.

Pollock’s universe, the universe of Mural, cannot be said to be a rational universe. Nor is it simply devoid of all sense. It is not a purely imaginary world, although in it everything is in a constant state of flux. Mural invokes one of the oldest questions of philosophy, a question going back to the Pre-Socratic philosophers Parmenides and Heraclitus – namely, whether the nature of Reality constitutes unchanging permanence or constant movement and flux. For Pollock, the only thing that is truly unchanging is change itself. The only certainty is that all is uncertain.

Mural is of course as much a psychology as it is a metaphysics – a vision of the nature of the self, as of reality. For Pollock these concepts are deeply intertwined because whatever we can grasp and express of the real is only possible in and through the self, the individual subject, or more specifically, the painter.

Mural then is a statement about what it means to be a painter, as much as it is a question of the meaning that a painting can have. The painter must be able to go within, to tap into the infinite collective reservoir of the unconscious. What emerges is not merely a psychological portrait of the painter (though it can be that) but has universal significance. There are many layers to our being, and some of those layers that lie deep within still reverberate with the primordial rhythms of the universe, grasped not simply as an aggregate of finite things existing externally to each other, but as having an inside, an interiority, an intelligence.

Pollock’s Mural is not the answer to a question, or the solution to a riddle. It does not pose us a problem or provide the key to solving one. Mural is simply returning to the beginning. Not a temporal or logical one, but a beginning that is irrecoverable, untraceable, always prior, always there. Mural is the grand, breathtaking attempt to arrive at the absolute presuppositions of painting. To paint as if first the first time. Pollock has begun the process – which he takes to the limit with the drip paintings – of dissolving the world, submerging all determinacy, particularity, and multiplicity into the One and All. Mural is an extraordinary achievement because Pollock is able at once to go entirely within himself, to turn his gaze inward, and find the Truth within his own subjectivity, without slipping into a dead-end solipsism. Pollock is after the universal, and Mural reveals a part of it.

*

Sam Ben-Meir is a professor of philosophy and world religions at Mercy College in New York City.