By Douglas J. Gladstone

SARATOGA SPRINGS, New York — Dick Sharon, a former San Diego Padres outfielder, is one of the chosen people.

The problem is, he’s been chosen – singled out, may be a better way to phrase it – by the suits who run the union representing today’s current players, the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA), not to receive a pension from Major League Baseball (MLB).

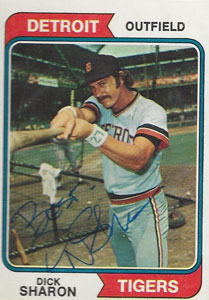

Currently a resident of Billings, Montana, the San Mateo native played for the Detroit Tigers during the 1973 and 1974 seasons before being traded to the Padres for the 1975 campaign. In 242 career games, he came up to bat 467 times, collected 102 hits, including 20 doubles and 13 home runs, and drove in 46 runs. He also scored 46 times.

Sharon — whose top MLB salary was a reported $19,000 in 1975– doesn’t receive a traditional pension because the rules for receiving MLB pensions changed in 1980. Sharon and the other men do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit. That was what ballplayers who played between 1947 – 1979 needed to be eligible for the pension plan.

Instead, they all receive nonqualified retirement payments based on a complicated formula that had to have been calculated by an actuary.

In brief, for every 43 game days of service a man had accrued, he’d get $625 up to the maximum amount of $10,000. Meanwhile, a vested retiree can earn a pension of as much as $230,000, according to the IRS.

For his approximately three years’ worth of service credit, Sharon receives a gross check of $5,625. And that is before taxes are taken out.

Also, the payment dies with the man. So when Sharon passes, his payment passes with him. Nothing to widows, children or other designated beneficiaries.

To date, the MLBPA has been loath to divvy up anymore of the collective pie. Even though the union’s pensions and welfare benefits fund is valued more than $4.5 billion, MLBPA Executive Director Tony Clark — the first former player ever to serve as leader of the union — has never commented about these non-vested retirees, many of whom are filing for bankruptcy at advanced ages, having banks foreclose on their homes and are so sickly and poor that they cannot afford adequate health care coverage.

Health coverage would have come in especially handy for Sharon, who estimates he’s had 25 orthopedic procedures and survives solely on his Social Security disability payments.

Sharon has never let the vicissitudes of life dull his sense of humor. When the Tigers named him their top rookie in 1973, he told The Sporting News that “it wasn’t all that difficult. I was the only rookie on the team.”

When he struck out three times in a game against Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan, in September 1974, he told Sports Illustrated that Ryan was “baseball’s exorcist. He scares the devil out of you.”

But there is nothing funny about this situation. The men like Sharon are being penalized for playing the game they loved at the wrong time. Other members of the Tribe – no, not the Cleveland Indians – who are in the same boat are former San Francisco Giants outfielder Don Taussig and Steve Hertz, a former infielder with the then-Houston Colt .45s (the team that became the Houston Astros) who managed the Tel Aviv Lightning in their lone season in the Israeli Baseball League in 2007.

I would personally love to see Sharon, who turns 70-years-old on April 15, 2021, receive a nice birthday gift from Clark, who fancies himself a social justice warrior. He received the Jackie Robinson Lifetime Achievement Award from the Negro Leagues Museum in 2016 but, so far, hasn’t at all lived up to the high standards of that great social justice pioneer.

Mind you, Clark isn’t just hosing the Jewish guys like Sharon, Taussig and Hertz. No, the onetime hoops star – he broke Bill Walton’s San Diego high school single season scoring record as a senior before later leading the San Diego State Aztecs with 11.5 points per game in the 1991-92 season – is an equal opportunity hypocrite.

Besides Sharon, Taussig and Hertz, others impacted by this injustice are such persons of color as Aaron Pointer; Cuban native George Lauzerique; Mexican-American Hall of Famer Cuno Barragan; Venezuelan Pablo Torrealba, and Panamanian Ed Acosta, who also played for the Padres in 1971 and 1972.

The biggest problem I have with this entire reprehensible affair is that the national pastime is an $11.5 billion industry. Why is it that pitchers Gerritt Cole and Stephen Strassburg, as well as third baseman Anthony Rendon, signed lucrative free agent contracts totaling nearly $950 million in 2019, but the union refuses to increase the bone that is being thrown the men like Sharon?

Sharon and others went without paychecks, endured labor stoppages and stood on picket lines, all so that today’s superstar players, such as Padres Manny Machado and Fernando Tatis Jr., can command what many would rightfully call obscene salaries.

I don’t begrudge them the money, mind you. But let’s respect the men who came before us.

So instead of this ridiculous actuarial computation that nets Sharon his onetime payment every February of $5,600, just give all these guys a flat $10,000 per year and then, after each passes, extend the payment for a finite time. With just 600 of these fellows left, $6.14 million is chump change in the grand economy of this business.

That way, nobody’s widow, like the late Linda Kidd Koch, could cry on the phone when she found out that the payment had been taken away from her.

I speak from first-hand experience. Two years after her late spouse, former Tigers hurler Alan Koch died, the Prattville, Alabama widow freely admitted to both myself and a friend, Phil Kahn, that she was having a tough go of it ever since his death.

“It costs money to get old, Mr. Gladstone,” she told me when we spoke that day.

Trust me, it was all I could do not to reach for the box of Kleenex.

Koch, who appeared in 42 career games over parts of the 1963 and 1964 seasons, won four games and pitched a total of 128 innings. For more information about his life, read this transcript of an interview he gave to Sandra Berman of the William Brennan Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta, Georgia.

By the way, after hanging up his spikes, Sharon opened up a fly fishing shop and now hosts international fly fishing trips. So you might say he went from shagging flies to catching ‘em.

If you want to go to bat for the men like Sharon, I encourage you to contact the union offices at 12 East 49th Street, 24th Floor, New York, New York 10017, or by telephoning Clark or union attorney Bruce Meyer at 212-826-0808 or 212-826-0809. Otherwise, please feel free to send an email to feedback@mlbpa.org.

*

Douglas J. Gladstone, who wrote an article about the television and stage producer Joe Stern for our paper in 2009, is the author of two books, including A Bitter Cup of Coffee; How MLB & The Players’ Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve.

You believe players with less than three years of service time should receive pension payments that total far in excess of their actual salaries? Makes no sense. No pension plan in the world goes back and gives pensions to earlier classes of workers.

Thanks for your continued support, Doug. I truly appreciate it. Dick

Pingback: Many MLB Veterans Struggle Without Pensions