By Donald H. Harrison

VENTURA, California – Not in Israel, as you might expect, but instead here along the Central California coast do you hear the words “Chumash” and “Jerusalem crickets” in the same sentence.

Susan Lamb, author of the National Parks Service’s souvenir book on the Channel Islands National Park informs us that “Many traditional stories express the Chumash sense that the sea is a mirror of the terrestrial world: sardines are like lizards, while lobsters match Jerusalem crickets. Islanders commemorated these beliefs and stories in dances, feasts and ceremonies that continued on the islands into the 1800s.”

In Hebrew, the word Chumash (cHu-Mash) refers to the Torah printed in book form rather than on a scroll. The word is related to Hamesh, which means “five.” There are five parts or books of the Torah.

If readers thought that Lamb was talking about the book form of the Torah, they might look in vain for any reference in Torah to sea life mirroring life on land. Furthermore, they would find nary a reference to a “Jerusalem cricket” because the insect that Lamb had in mind is neither from Jerusalem nor a cricket.

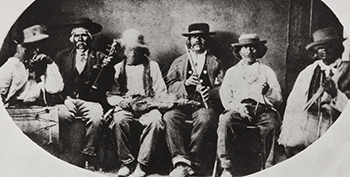

The Chumash (Chew-mash) to whom Lamb referred are an indigenous people who live on the mainland of Central California and previously resided as well on four offshore Channel Islands that extend from east to west in a near straight line: Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel. Another island, Santa Barbara, lies well to the southeast of Anacapa.

Various place names in California have Chumash origins, according to Wikipedia. Among these are Cayucos, Malibu, Nipomo, Lompoc, Ojai, Pismo Beach, Point Mugu, Port Hueneme, Piru, Lake Castaic, Saticoy, Simi Valley and Somis.

As island dwellers, the Chumash were adept at boating and fishing. In fact, their canoes known as “tomols,” were so expertly fashioned that the Spanish explorer Sebastian Vizcaino, who passed by the islands at the very beginning of the 17th century, marveled that they were “so well constructed and built that since Noah’s Ark a finer and lighter vessel with timbers better made has not been seen.”

Lamb also reported that “the Island Chumash traveled extensively in tomols, crossing the Santa Barbara and the ocean between the islands to trade, marry, and conduct ceremonies. Using drills of local chert, they made beads from Olivella shells as a form of currency. This currency circulated throughout southern California, part of a broader network of indigenous trade routes connecting much of the American west.”

Today, only a remnant of the Chumash peoples remain. Their ancestors were victimized by European diseases and colonization. A small reservation for the Chumash people is located on the mainland in Santa Barbara County near the old Santa Ynez Catholic Mission.

Here in Ventura, at the Visitor Center named for former Republican Congressman Robert J. Lagomarsino, exhibits and written materials tell the story of the islands across the channel from paleolithic times to today. The National Parks Service and its partner the non-profit Nature Conservancy are working to restore the islands’ ecology to the period before private ranching decimated some animal and plant species and altered landforms.

From visitor center materials and those from the nearby Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, we learn more about the Chumash people and that insect mysteriously named the “Jerusalem cricket.”

Midden sites filled with shells and fish bones “reveal that although the islanders exploited terrestrial plant resources, such as acorns and cherries, they subsisted primarily on fish, shellfish, and other marine organisms,” according to the Park Service’s interpretive guide for eastern Santa Cruz Island. “The midden also reveals that other items, not available in this isolated island environment had to be obtained from villages on the mainland or other islands. One of the principal products manufactured and traded by the islanders was shell beads, which were the currency of trade in the Chumash area and throughout California. Chert microdrills were used to bore holes in pieces of Olilvella snail shells to produce these beads. Not only did the islands have an abundance of Olivella shells, but, even more importantly, eastern Santa Cruz Island also had considerable natural deposits of chert, a hard durable silica rock.”

The guide, written by Derek Lohuis with contributions by John Gherini and Dewey Livingston, reveals in a discussion about native plants much about the lives of the Chumash.

For example, the guide reports that toyon, also known as California holly, was a “valuable source of hardwood for manufacturing a variety of implements such as arrows, harpoons, fish spears, digging sticks and gaming pieces. The Chumash often used heat or steam to shape and form objects made from toyon and other hardwoods. For example, bundles of toyon arrows were steamed in earth ovens to make the rods pliable; the shafts were then straightened and allowed to dry. After drying, the arrows were trimmed to the proper size, the points shaped and hardened in hot ashes, and feathers added.”

Acorns and island cherries both could be boiled, then leached of their tanins and “mashed to the consistency of refried beans.”

The sweet prickly pear fruit features a beet-red juice that can be used as a paint and die. Its thorns were used for ear piercing and tattooing. In the wild cucumber, there are several large black seeds, that can be extracted after the fruit dries. “The Chumash made necklaces of these seeds, polishing them along their oiled bodies. They were also used as marbles by Chumash children.”

There are four native mammals in the Channel Islands National Park. The island fox, island deer mouse, harvest mouse, and the island spotted skunk. The fox is omnivorous and the spotted skunk is carnivorous. Either way spells trouble for the Jerusalem cricket, which is the spotted skunk’s most frequent prey.

Wikipedia informs that “Jerusalem crickets (or potato bugs) are a group of large, flightless insects in the genera Ammopelmatus and Stenopelmatus, together comprising the subfamily Stenopelmatinae. The former genus is native to the western United States and parts of Mexico, while the latter genus is from Central America. Despite their common names, these insects are neither true crickets (which belong to the family Gryllidae) nor true bugs (which belong to the order Hemiptera), nor are they native to Jerusalem. These nocturnal insects use their strong mandibles to feed primarily on dead organic matter but can also eat other insects. Their highly adapted feet are used for burrowing beneath moist soil to feed on decaying root plants and tubers.”

So, how did they become known as “Jerusalem” crickets? It’s a matter of speculation. Wikipedia explains: “Several hypotheses attempt to explain the origin of the term ‘Jerusalem cricket.’ One suggests the term originated from a mixing of Navajo and Christian terminology, resulting from the strong connection Franciscan priests had with the Navajos in developing their dictionary and vocabulary. Such priests may have heard the Navajos speak of a “skull insect” and took this as a reference to Calvary (also known as Skull Hill) outside Jerusalem near the place where Jesus was crucified.”

The so-called Jerusalem crickets range over the western United States, including the Navajo lands of New Mexico. Whereas true crickets rub their legs together to call to potential mates, the “Jerusalem cricket” exhibits a different behavior. According to Wikipedia, it rubs its legs against its abdomen to make a hissing sound, not for mating purposes but to scare off predators.

This is disputed by Dylan Otte, a naturalist with the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. “Jerusalem crickets are talented drummers!” he writes. “To attract a mate, both the males and females drum their abdomens on the ground. There are several species of Jerusalem Cricket and they all have a unique drum. Eggs are laid in groups in the soil. When they hatch, they have about a two-year life span ahead of them!”

Excursions to the islands ranging from several hours to several days may be arranged at the Robert J. Lagomarsino Visitors Center at 1901 Spinnaker Way in the Ventura Harbor Village.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Indeed, the Chumash freeway, not far from SB-Solvang, is a quaint road that always reminds me of the way grandpa used to call the Torah. Chumash obviously comes from Chamesh, 5 in hebrew.