A Sunday Reader: The Life of Mark Strouse (1845-1898)

Editor’s Note: This article, at nearly 8,000 words, is much longer than most articles presented on the Internet. Meant for people who enjoy reading about American Jewish history, it will take a commitment of time to read in its entirety.

By Susan E. James, Ph.D.

LA CANADA-FLINTRIDGE, California — During the 1870’s, the population of Nevada’s legendary Comstock Lode, then at the height of mining fever, surged to nearly 25,000. In the canyons and down the slopes, housing was scarce, the noise was unceasing, the air nearly unbreathable and the violence endemic.1 Between them, the towns of Virginia City and Gold Hill were a crowded jumble of miners’ cabins, stamp mills, luxury mansions, hotels, restaurants, saloons, stores and stables, all built over an underground city of mining tunnels, adits and shafts. These underground works ultimately produced over 300 million dollars’ worth of precious ore that built the city of San Francisco and made fabulous fortunes for the fortunate.

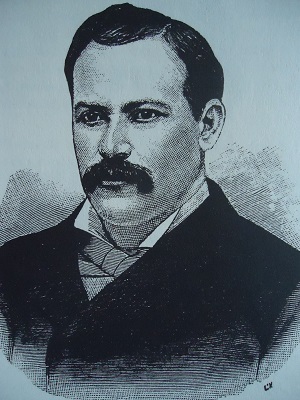

Among this crowd of fortune-seekers lived a Jewish community of about 500, and one of its most influential members was a butcher from Germany named Mark Strouse (1845-1898). Besides his butcher’s business, Strouse was an ambitious merchant, rancher and entrepreneur, who combined economic affluence with civic service and political aspirations. He held at various times the offices of city treasurer, of foreman of a volunteer fire department, and of chief of police. Yet during his residence in Virginia City, besides success, he also achieved unwelcome notoriety through the scandal that resulted from his marriage to and divorce from 18-year-old Lillie Edgington, the belle of the Comstock.

Origins

Mark Strouse was born in central Germany on 20 May 1845, the youngest of the ten children of Bila (Bertha) and Moses Strouse (or Strauss). Originally from the tiny town of Storndorf, where Bertha was born, the family had moved eight miles east to the town of Lauterbach just before Mark’s birth.2 Now in Baden-Württemberg but then part of the patrimony of the Grand Duchy of Hesse, by the mid-19th century Lauterbach was home to a small scattering of Jewish ‘cattle dealers, merchants and shopkeepers’.3 By 1864, in fact, only 11 Jews were listed as living in the town, and by 1880, in a population of 3295, that number had barely risen to 32.4 Lauterbach was not a place that welcomed Jewish residents, and the enterprising and ambitious Strouse understood early on that there was little future for him there. At 13 he left home, moving west to the town of Butzbach, some 22 miles north of Frankfurt. Two years later, together with his sister Amelia, Strouse left Germany for good and emigrated to America.5

The teen-aged Strouse made his way west, settling in the California gold camp of Mokelumne Hill in Calaveras County, about 55 miles southeast of Sacramento. The camp was built on appropriated Miwok tribal lands and had boomed in 1848 when gold was discovered in the local streams in such abundance that during the next two years 15,000 people swarmed the site. By the time the Strouse brother and sister arrived 12 years later,

however, the ore was playing out, and although Mark first tried his hand at mining, he had little success. He soon realized that there was greater opportunity and considerable profit in feeding hungry miners instead.

The Comstock and Central Market

Leaving Amelia in Mokelumne Hill, where she was joined by her widowed mother, sister Sarah and two brothers Abraham and Kalman, Mark scraped together sufficient funds to buy 5,500 head of sheep, and in June 1863 drove them 150 miles northeast across the snow-filled passes of the Sierras to the recently established boomtown of Virginia City. His investment paid off, and at the age of 18, Strouse had made enough from the sale of his sheep to buy a 500-acre ranch on former Washoe Indian land at Honey Lake, California, about 85 miles north of Virginia City.6 His ranch provided him with a steady supply of beef and mutton intended for the Comstock market, and despite his devotion to Judaism, he raised and sold a full supply of pork products as well.

Establishing himself in Virginia City, where he set up several local slaughterhouses to process his meat, Mark Strouse became the personification of boomtown Comstock’s zeitgeist, an immigrant entrepreneur who through imagination, skill and an obsessive attention to business was remarkably successful in a very competitive market. Physically big, with endless energy and ready fists, he was a self-invented man.7 By the end of 1863, he had entered into partnership with his older brother Abraham. The two hired three additional butchers and opened A. Strouse and Brother Market, a butcher shop at 17-18 South C Street, Virginia City’s main commercial thoroughfare. As Abraham was the older brother, Mark gave him top billing and accepted for himself the role of ‘and Brother’.

While Abraham devoted all his efforts to the business, even living next door to the market, Mark had his eye on social as well as economic advancement and took a house at 23 South A Street. It was Mark, too, whose entrepreneurial skills made the enterprise a success. By 1864, Mark had changed the name of the business to the less cumbersome Central Market, and it quickly grew into a prominent four-story, 3000-square-foot Virginia City landmark occupying a whole east-west block between C and D Streets.8 Inside, the ground floor was partitioned into stalls, each with its own specialty. There were stalls for beef and veal, a stall dedicated to the sale of pork and sausages, one for fish and oysters, and several others for vegetables and groceries.

Strouse also maximized his profits by sub-leasing a number of his stalls to other merchants, preferably German immigrants or those of German descent, advertising: ‘Stalls (for rent) at the Central Market; also, the whole floor upstairs, containing 17 rooms … Terms Reasonable.’9 On 15 April 1876, the Territorial Enterprise announced that ‘a new grocery store’ under the management of 22-year-old Gustave Lippman had opened inside Central Market. According to the advertisement, it offered ‘a first-class assortment of Fine Groceries and Liquors. We keep on hand Fresh Fish, Vegetables and all descriptions of Fruit in season. Canned Goods of all kinds. Cutter and Kentucky Favorite Whiskies a Specialty. ’10

In a hyper-competitive town, a market had to work hard to stand out above the crowd, and Strouse worked hard to do everything he could to raise the profile of his business. In 1864 in Virginia City alone, there were already 15 butcher shops and 30 markets vying with each other for customers among a population of roughly 10,000.11 Although the population, together with the demand for goods, was growing rapidly, flamboyance and imagination were required to tempt consumers and beat out the competition. Not only did Strouse consider the needs of Virginia City’s kitchen cooks, he also supplied products for the industrial needs of the town’s multiple mines, mills, and livery stables, selling grease as wheel and gear lubricants. In one advertisement, Strouse assured a variety of customers that he could provide ‘all kinds of fresh and salt meats, ham bacon and lard of my own cure. Rendered tallow for mill and mining purposes at wholesale or retail.’12

In 1877, Strouse bought out the Cooper and Hill grocery store, ‘connected with my market’, and opened a delivery service free of charge, ‘to furnish families at the shortest notice, delivered at residences and fresh every morning’.13 Like its owner, Central Market was big and extravagant, catering to every conceivable need, and in the late 1870’s it also became the only kosher meat market in town catering for the Jewish community. Kosher meat before Strouse entered the marketplace was expensive as it had to be ordered all the way from Sacramento, so in 1878 Strouse hired a Polish rabbi and shochet or kosher butcher named Solomon Aragor.14 For the next two years, Central Market was the only place the Comstock Jewish community could buy kosher.

*******

On 24 October 1868, five years after its founding, Central Market lost one of its partners when Abraham Strouse died and was subsequently buried in the Jewish cemetery back in Mokelumne Hill.15 Their brother, Kalman Strouse, had died there just five months earlier, and although Bertha Strouse and her two daughters still lived in Mokelumne Hill, they would later move to the Comstock. With A. Strouse gone, Virginia City’s ‘And Brother’ took over the entire business, offering a prime stage for Mark Strouse’s showmanship.

Exotic meats were a specialty with hand-reared bear, elk and deer meat often on display. On 24 February 1878, the Territorial Enterprise described one typical Strousian spectacle. ‘At the Central Market, Mark Strouse, proprietor, there was yesterday to be seen a dressed bullock that weighed 1,635 pounds … Porterhouse steaks cut from the animal would have made an overcoat for a man of ordinary size’.16

For its holiday displays in particular, Strouse’s market was celebrated. One local resident remembered that during the holidays it was fixed up ‘in a very tasty and ornamental style … [with] nice fat meats of every kind used, trimmed off with roses and artificial flowers, cut out of tissue paper, with their great display of elks and bears’ heads.’17 Strouse would arrive at his market at four in the morning, put on his butcher’s coat and start to work. His habit was to remain at the market after closing and ‘continue laboring over accounts and sales until nearly midnight.’18 Commenting on Strouse’s business reputation, one customer later remarked that, ‘[His] market has firmly established a name for first-class meat and fair dealing that no person or company can rob it of,’ while another proclaimed, ‘Mr. Strouse’s reputation for honesty and fair dealing has contributed largely to the success he enjoys.’19 Such intense focus on business brought commercial success, and in a location where supply was an issue and quality and freshness often lacking, Strouse’s ownership of the supply chain and processing premises, together with a concentration on artisanal standards in the products he sold stood out among his competitors.

Business Investments

No matter how diverse the threads of his expanding business empire became, Mark Strouse never forgot his beginnings as a butcher, and his core identity was grounded in his most successful commercial enterprise, Virginia City’s Central Market. But like a miner

searching for promising new strikes, Strouse was always on the look-out for promising new investment opportunities. While he would eventually run the largest meat business in Nevada, a decade after the market’s founding, Strouse went into two ancillary businesses with a recent arrival from Maine named Philo Knapp. Together, they opened the Virginia Ice Company on E Street, which Knapp continued to run as late as 1900, and the Knapp and Strouse Wood and Coal Company that was ‘prepared to furnish wood and coal, in quantities to suit, at the Lowest Market Prices, delivered in any part of the town.’20

In June 1871, Strouse also went into partnership with one of the Comstock’s famed ‘Silver Kings’, James G. Fair, in the purchase of the Occidental mine and mill.21 Returns on this investment were disappointing. Tunnels driven at ever-lower depths yielded little high grade ore. Between 1866 and 1894, only $400,000 was extracted from nearly 40,000 tons.22 Occidental stock sank from $10 a share in May 1872 to $3 a share by February 1875.23 But like all gamblers on the Comstock, mining investments continued to attract Strouse. He bought 1000 shares in the Bounty Mining Company and acted as a trustee for both the Phil Sheridan Mining Company and the Big Oak Flat Gravel Mining Company.24 Purchased on the heels of the Comstock’s Big Bonanza of 1873, these investments held out hope for a rich return, but, like the Occidental, they seem to have produced less than stellar results. Mercantile and mining investments were joined in 1874 by property investments when Strouse bought an interest in the Randolph House Hotel which was struggling financially. By August he was placing advertisements soliciting renters, and by October 1875 the hotel vanished in flames. Although many of his investments failed to pay huge dividends, in November 1877, Strouse was listed as one of the directors of the Virginia Savings Bank on C Street, a position he was unlikely to have achieved without considerable personal funds.25

Political Offices

By the early 1870’s, Strouse was both well-known on the Comstock and a very wealthy man. But financial success was only the first step on the social ladder for Virginia City’s preeminent butcher. Mark Strouse was an ambitious man, and the melting pot of the Comstock opened opportunities to him that he would never have had back in Lauterbach. He joined the local Masonic Lodge, where the movers and shakers of the area met, and became friends with its grand master, Abram Merkel Edgington. For seven years, he was the foreman of Company No. 1 of the town’s volunteer fire department.26 In May 1868, he successfully ran for the office of chief of police for Virginia City, a job that on the ever-violent Comstock involved real danger.

The Sacramento Daily Union for 5 June 1868 recounted the capture of one ‘Riley’, a man wanted for the murder of the Ormsby County sheriff. Riley had been injured by the pursuing posse, and Strouse, ‘who left this morning at 2 o’clock … will bring him to this city, dead or alive’.27 At the end of September in the same year, small pox broke out, and as police chief, Strouse was responsible for hunting down the infected and tacking a yellow quarantine flag on their door. ‘Down on E Street,’ wrote the Gold Hill Daily News on 1 October, ‘in a house of ill-fame … one of the cyprian inmates, last evening, was officially reported to have [the disease], and Chief Strouse went and nailed a yellow flag to [her door]’.28 Risk from gunmen and virulent disease there may have been, but, according to the Gold Hill Daily News, Strouse was not above using his position for his personal benefit or to intimidate rivals. On 2 June, the editor of the paper complained that ‘Not only Chief Strouse … but one of the regular policemen under him … came down and kicked up a muss at our town election yesterday … We had trouble enough with the roughs of Virginia interfering with and trying to control our town election, without any of their police force chipping in and meddling.’29 Accusations of bullying electors in Gold Hill did his reputation little damage in Virginia City, and when his term as police chief was over, Strouse ran for city treasurer, won, and held that office for two terms.

The Belle of the Comstock

By 1873, having staked his claim to financial success and civic recognition, Strouse, now 28 and one of Virginia City’s most eligible bachelors, set about the business of establishing a Strouse dynasty. Driven by overmastering infatuation, he pursued a bride outside the Jewish community. The target of this infatuation was the belle of the Comstock, Lillie Bailey Edgington. As described by the Reno Gazette-Journal, Lillie Edgington was strikingly beautiful, ‘being of a tall, slender and graceful figure, with large blue eyes, a sweet mouth, delicate complexion, and of a very intelligent cast of countenance.’30 Among the denizens of the Comstock, she ‘made a magnificent appearance … Her dresses were among the finest seen’.31 Beautiful, charismatic, strong-willed, and just eighteen, Lillie was the stepdaughter of Abram Merkel Edgington, businessman, entrepreneur, Grand Master of the Virginia City Masonic Lodge, a prominent member of the Protestant Episcopal Church, and reputed to be one of Virginia City’s wealthiest citizens.32

Determined to marry Lillie and encouraged by her parents, sadly for Mark Strouse things were not all they seemed. Since her schooldays when she was barely fifteen, Lillie had been involved in a clandestine affair with her schoolmaster, Julian Janes. She had no desire to marry the man her parents had chosen for her. The senior Edgingtons, too, were maintaining a false front. Despite the common belief that they commanded great wealth, the truth was that the ‘Colonel’, as Abe Edgington was known, had lost a fortune buying and betting on racehorses. When Lillie strongly objected to marrying Strouse, this embarrassing financial fact was brought home to her by her mother, Mary. Lillie’s lover Julian Janes was summarily bought off and left town abruptly to attend to ‘business in the East’. With his departure, the Edgingtons, and in particular Mary, took matters into their own hands and strong-armed Lillie into accepting Strouse’s marriage proposal. ‘Now,’ commented the Reno Gazette-Journal rather snidely, ‘anyone who has seen [Lillie] and knows Mark Strouse, understands perfectly well that a woman of feeling and refinement would not be the happiest being in the world were she compelled by her people to marry the man for his money.’33

Lillie Bailey Edgington married Mark Strouse on 14 January 1874 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on the corner of F and Taylor Streets with Reverend Whitaker presiding.34 It was the social event of the season and most of Virginia City showed up to watch or to the participate in the festivities. One invitee noted in his diary: ‘Drove to St. Paul’s church – so crowded inside and out that we staid (sic) in front in carriage and watched [com]motion – when crowd came out we drove up to Edgington mansion on B St. to reception – Grand Affair – Big Crowd – Whole house thrown open – plenty of waiters – band of music – big time – plenty of cake and wine – dance, etc.’35 According to the Gold Hill Evening News, at the wedding reception, ‘the happy bride and groom stood in a beautiful alcove at the south side [of the parlor] festooned with lace curtains and almost surrounded by luxuriantly growing natural flowers as the mother of the bride happily expressed it, all reared by herself, including the fairest Lily of them all.’36

Strouse and his reluctant bride moved into an elaborate residence at 56 South B Street, just north of the Edgington mansion, a sign that Strouse intended to support his wife in the same style to which she was accustomed. That he had pursued a non-Jewish bride and consented to marry her in a Christian church rather than a traditional Jewish ceremony argues the depths of his feelings; Lillie’s attitude, on the other hand, was less that of devoted wife and more that of the sole shareholder in a particularly lucrative bank. For her, Strouse was a cash cow useful in supporting her position as the most fashionable lady on the Comstock.

Harry Gorham, a journalist who knew her during these years, compared her to Lily Coit of San Francisco, a free-wheeling, free-spirited eccentric, given to smoking cigars and prowling gambling dens dressed like a man. ‘Lily (sic) Edgington was never still,’ Gorham wrote. ‘[She was a free soul], independent in thought and action.’ He went on to tell a story that helps illustrate her attitude toward both her husband and Virginia City.

Maybe you can imagine the kind of girl she was when

I tell you of her going into Meyers Dry Goods Store and

asking Meyers if he had anything new in stock that might

interest a female who wanted to look her best in company.

“Yes, Lily,” said Meyers (for she was known to all by

her first name), I have just received in stock some of the

prettiest jabots I have ever seen.”

“Show me one,” said Lily, and in answer to her request

he placed on the counter some of those delicate little articles,

something, I think, like a soft, ruffly collar. It immediately

caught Lily’s eye.

“How much?”

“They are ten dollars each,” answered Meyers.

“How many have you got in stock?”

“I have an even two and a half dozen,” was the

polite response.

“If you will promise not to import any more of them,

you may send them all up to the house and charge them to

Mark,” said Lily.

And to show Meyers how she felt about it, she added,

“No tart in this town is going to run around and say that she

has the identical neck fixin’s that Lily Edgington has.”

Gorham added one more story related to another shopping expedition that could only have happened in a boom or bust mining town. Lillie was in Emanuel Mandel’s store where she asked to see a shirtwaist in a box on a high shelf. ‘Manuel had to climb up on a ladder to reach it … And after a moment from that height, he looked down and asked, “What bust, Lily?” “Darned if I know, Manuel – I didn’t hear anything.”’37 These stories illustrate Lillie’s patronage of shop owners who belonged to her husband’s Jewish community, but they also show her continued self-identification not as Mrs. Strouse but as ‘Lillie Edgington’ and, despite her exalted social position, her lack of pretense among the denizens of the rough mining town where she had grown up and was known to all as ‘Lillie’.

Even if her marriage was not to her liking, Lillie nevertheless did her duty by the Strouse family line and presented her husband with their first child, a daughter, just ten months after their wedding on 14 November 1874. Strouse named the child Bertha for his mother and as an adult Bertha Strouse looked much like her father. This may be one reason why Lillie showed no particular interest in the new baby and continued to focus on cutting a swath through Virginia City’s fashionable society.

The Great Fire of 1875

Just before dawn on the morning of 26 October 1875, at a boarding house on South A Street owned by a widow known as ‘Crazy Kate’ Shea, a candle was knocked over near the toilet and set fire to the building. The fire soon spread to William Mooney’s livery stable located right behind the boarding house where combustible materials exploded in all directions, the flames fanned by arbitrarily gusting winds. By 8:00 a.m., wrote the Sacramento Daily Union, ‘the scene beggared description. The streets were filled with people; teamsters were struggling through, and firemen fighting the fire at all available points. Women were shrieking; the cries of despair; the curses of enraged men; the roar of the flames; the dull reports of explosions as building after building took fire; the heavy thud and crash of falling walls; the snap of bursting iron bars and doors; the howl of the gale – all went to make up a scene of indescribable horror.’38 Church bells rang heedlessly; mine whistles shrilled through the clamor adding more panic to the terrified town. Over the next nine hours, the Randolph House Hotel and Mark Strouse’s Central Market vanished in a sea of flames. By evening, thousands of Virginia City refugees were strung out over the hillsides with the few belongings they had managed to save. The air was full of smoke and ash, and with the bitterly cold night came the first snowfall of the season.

The fire leveled most of Virginia City, displacing as many as 6000 people. Mark Strouse had lost his market and his business, but by the slimmest of margins his house was still standing. According to the Owyhee Daily Avalanche, the fire ‘crossed over to Taylor Street, and burned Curly Bill’s livery stable, the Eagle Fire Engine Company’s house and Wm. Wood’s residence. The residence of Mark Strouse, adjoining Wood’s, caught fire, but was put out by the hand engine of Eagle Company No. 3, which was detained at the G and C cistern at the commencement of the fire, and kept the same position during the day and did good service on the east side of B Street.’39 That the east side of B Street was known as ‘Millionaires Row’ and housed the elite of the town might explain why it received the focus of ‘good service’ by Eagle Company No. 3. It was also helpful that Strouse was a leading light in the volunteer fire brigade which might have determined the positioning of the fire engine that saved his home. But despite the reassurance of still having a roof over his family’s head, in the days after the fire, Strouse’s public image as a generous and engaged member of the community, a reputation that he had cultivated so assiduously since 1863, suffered a sharp blow.

The Strouse clan, Mark’s mother Bertha and his sisters Sarah and Amelia, together with their husbands and children, had followed the ascendant star of his success in Virginia City and relocated from Mokelumne Hill to the environs of the Comstock. With their six children, including a son named Mark and a daughter named Lillie, Sarah and her husband Lehman Weil, a Bavarian-born butcher, moved to Cedar Ravine at the north end of Virginia City.40 Besides caring for her family, Sarah Strouse Weil undertook, as so many women on the Comstock did, additional labor by running a boarding house to supplement the family income. Amelia Strouse, the sister with whom Mark had originally immigrated to the U.S., had married a Scottish miner from South Ayrshire named James McCreadie and lived with him and their three children on South A Street.41 Mark’s mother, Bertha, lived with the McCreadie family.

In the days after the fire, a Relief Committee composed of some of the most powerful men on the Comstock – William Sharon, George Dodge and James Flood– was called into existence to oversee the collection and distribution of food and clothing to those in need. While making his rounds among those needy, Richard Wheeler, the secretary of the committee, discovered the dispossessed Bertha Strouse and Amelia Strouse McCreadie huddled for shelter in Mark Strouse’s surviving slaughterhouse. Where Amelia’s husband and children were is unclear but as orthodox Jews, above and beyond any other discomforts, staying in a space where pigs were regularly butchered would have been anathema. Wheeler reported the condition of the two women to the Relief Committee, which was officially appalled, and the publicity generated by their situation aroused expressions of outrage among the Comstock community. That so wealthy a citizen as Strouse, whose own house was still standing, should have left his mother and sister to freeze in a slaughterhouse raised communal hackles. Strouse’s public reputation suffered from the outcry and his excuse, that the women preferred the inconveniences of the slaughterhouse to the comforts of his own home, was both shocking and unconvincing.

According to the San Francisco Weekly Stock Report and California Street Journal for 5 November 1875:

Mark Strouse, the rich man whose mother and sister

have been supplied with food, bedding and clothing

[by the Relief Committee], comes out in a card to-day

in the Enterprise, denying the charge of heartlessness

and neglect made by the Relief Committee. He says he

has provided for them well and has seen that they wanted

for nothing; that they preferred to take up quarters in a

slaughter house rather than in his own splendid residence,

because their tastes are simple in the extreme, and that the

story printed about him is gross slander. On the other side

we have the Secretary of the Relief Committee, who says

that he visited old Mrs. Strouse and her daughter, and found

them in a most extreme state of destitution, having no

clothing, no blankets, no food – nothing whatever. The

Secretary was directed to correspond with Strouse by

a unanimous vote of the Committee.42

Neither woman was in robust health after her ordeal. Bertha Strouse died in 1878 and Amelia in 1879, but the full truth of the situation is hard to determine from the printed reports. Whether Richard Wheeler was targeting Strouse with exaggerated slander because of personal animosity or whether Strouse was guilty of familial neglect is unclear. No one from the newspaper appears to have personally interviewed the women in question. Whatever the truth, the rumors did Mark Strouse’s reputation little good.

The Strouse-Edgington Divorce

On 13 May 1876, Lillie gave birth to her second daughter whom she named Abby for her father who had died the preceding year. Abby, like the grandfather for whom she was named, was fragile and four months later, on 13 September, she died suddenly. Both parents were overwhelmed and rather than simply bury their dead baby in the Virginia City cemetery as was customary, Mark Strouse paid for a formal funeral, announced in the local papers, which took place ‘from the residence of the parents, B Street, near Taylor, on Wednesday, 13 September, at 3:00 in the afternoon.’43

By January 1877, Lillie was pregnant again and less than a year after Abby’s funeral, she gave birth to her third child, a son. Shortly after the birth, the Territorial Enterprise for 6 September carried the sad news that: ‘After only a few hours’ illness, yesterday, the infant child of Mr. and Mrs. Mark Strouse died. The afflicted parents are wild with grief over the bereavement.’44 Within four years, Lillie had buried her father, said good-bye to her mother who had moved to San Francisco, and watched helplessly at the deathbeds of her two younger children. Strouse had suffered the death of his children as well, but the death of his father-in-law could hardly have been the crushing blow it was to his wife. The death of the longed-for Strouse male heir, on the other hand, seems to have been the final breaking point for a marriage that was doomed from the beginning.

Sometime after Abe Edgington’s death and Mary Edgington’s move to San Francisco, Julian Janes returned to Virginia City and took a job as tutor to the two sons of Silver King and Strouse business associate, James G. Fair. The Fair mansion at 69 South B Street stood directly across from the former Edgington mansion and just down from the Strouses. Proximity and Janes’ renewed advances led to the resumption of his affair with Lillie. According to divorce papers filed by Mark Strouse on 13 August 1878, Lillie Strouse, ‘who is the wife of the said plaintiff on the 28th day of July A. D. 1878 at the Bower’s (sic) Mansion in the County of Washoe, in said State of Nevada, did commit adultery with one J. C. Janes, and did commit adultery with said J. C. Janes at divers places in the said County of Storey and State of Nevada at divers other times between the first day of April A. D. 1878 and the said 28th day of July A. D. 1878.’45 Lillie rebutted the charges in court but did little to fight the divorce which was granted on 14 August 1878.

The resultant scandal caused a sensation on the Comstock and a frenzy in the press. Notoriety would follow the errant wife for the next decade. The Nevada State Journal remarked with sarcastic understatement that: ‘The case is one that has created great excitement in Virginia City(‘s) high-toned circle.’46 By the time the divorce was finalized, Lillie and her paramour were in Reno where they married the following day. Janes, who was a persuasive conman, was under the impression that he had secured a treasure chest in Lillie. When he found that was not the case, he pawned everything of value she owned and abandoned her four months after their wedding in a two-room flat in Oakland. Rescued by her mother and on Mary’s advice, Lillie tried to reconcile with Strouse, ‘but he, being a man of sound mind, utterly refuses to listen to such a preposterous proposition.’47 Now destitute and desperate, Lillie took the radical step of staking her notoriety on a stage career, making her debut on 7 December 1880 in San Francisco at the Baldwin Theatre as Pauline in ‘Lady of Lyons; or, Love and Pride’, a five-act melodrama written in 1838 by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.48

The reviews were not encouraging. According to the theater critic of the San Francisco Examiner, ‘It would be useless to enumerate the faults of the amateur. The stage and its art cannot be learned in a couple of months … Miss Edgington has a good stage presence, a clear and musical voice, she does not lack intelligence, and with hard study and a disposition to accept any part that may be offered to her, there is little doubt that she will eventually become … a good actress.’49 Despite the doubters, Lillie did become a good actress, spending eight years on the stage in San Francisco and New York. In the years that followed her retirement from the theater, she moved around the country, remarried four times, and died on April Fool’s Day, 1917, in the tiny mining town of Mina, Nevada, only a hundred miles from where she had grown up on the Comstock.50

*

After his acrimonious divorce, Mark Strouse sold the B Street mansion that he and Lillie had shared, fostered his 5-year-old daughter with his sister and moved into Rosa Connors’ boarding house at 17a South C Street, across the road from the rebuilt Central Market.51 Virginia City while still outwardly prosperous had begun a slow decline that by 1880 would see its 1874 population halved and by 1900 would see it reduced to less than 3000. Responding to the drop in business, in 1879 Strouse placed a notice in the Territorial Enterprise that from then on, he would accept only cash at Central Market. Too many people were buying on credit.52 Besides business troubles, the scandal of his ex-wife’s adultery and Julian Janes’ abandonment continued to be the stuff of local and not so local gossip. Lillie’s well-publicized entrance on the San Francisco stage in 1880 only fanned the flames. On 1 March 1881, the Territorial Enterprise announced that, ‘Mark Strouse has shaken the dust of the Comstock off his feet and gone to San Francisco, to start the same business. We are sorry to lose Mark.’53 It is unlikely that Mark was sorry to go.

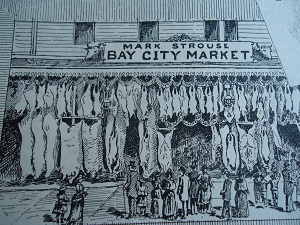

Bay City Market and the San Francisco Meat Wars

In San Francisco, Strouse’s business acumen served him well. He opened Bay City Market at 1138-1146 Market Street, and with his usual panache, blazoned his name inside and out. As he had in Virginia City, he joined a collection of fellowships, South San Francisco Masonic Lodge No. 212, the Eureka Benevolent Association, the Odd Fellows, the Independent Order of Foresters, and the Veteran Volunteer Firemen’s Association. He maintained his contacts on the Comstock and continued to speculate in mines and mining stock, filing a mineral patent together with fellow immigrant John Rapp on the Brunswick Lode in the Silver Star mining district of Storey County in September 1881.54 He married again, this time to someone more suitable to his needs and aspirations, a fellow German Jewish immigrant 17 years younger named Emilie Buhlert (1862-1933). Emilie became the wife and companion that Lillie Edgington could never have been. She was the daughter of Albert Buhlert, who in 1860 was working in Mokelumne Hill with Mark’s older brother, Abraham.55 Such close family ties over decades among the extended German Jewish communities of California and Nevada suggest just how much of an outsider Mark’s first wife must have been. Like Lillie, Emilie gave birth to three children, only one of whom, Mark, Jr., lived to adulthood.

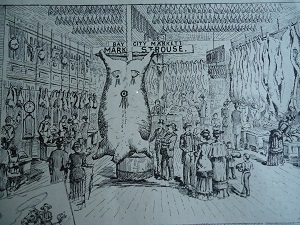

In Virginia City, Strouse had raised bears for meat alongside his pigs and continued this tradition in San Francisco. ‘No butcher in the city,’ wrote the San Francisco Examiner, ‘shows the energy, the enterprise, or such an elegant display … as Mark Strouse of the Bay City Market’.56 Inside the new market, headless bear carcasses decorated with paper rosettes hung from the market’s central rafters while parallel rows of butchers stood behind cutting blocks set against the side walls ready to cut meat to order. The exterior frontage of the building was festooned with whole carcasses of beef and pork hanging on display side by side like corrugated curtains. The effect was opulent, ostentatious, and part of the conspicuous consumption credo of the West.

San Francisco’s Bay City Market like Virginia City’s Central Market exhibited a butcher’s delight in a carnival of animals, domestic and exotic, as gustatory offerings.

Holiday seasons summoned forth exceptional exhibits … featuring hundreds of cattle, sheep, lambs, and “porkers ranging up to 1270 pounds in weight,” as well as two black bears. The bears were apparently a hit; a couple of years later Strouse included three huge bears in his Christmas display: an Alaskan bear, a British Columbian bruin, and a California cinnamon bear. And, in 1895, he displayed a huge grizzly bear, just when the California grizzly was becoming extinct.57

The downside of the Strouse live bear circus occurred at Christmas 1896 when The San Francisco Call blazoned a headline reading ‘Mark Strouse’s Bruin Discovered Under Tallow Works’ and went on to describe the bear’s escape and the ensuing attempt by two local men to pursue the animal and earn the reward that Strouse had offered for capturing it. No reward was collected; the men were badly mauled, and the bear remained at large.58

Known in Virginia City as an aggressive businessman, the move to San Francisco did nothing to mellow Mark Strouse. Cutting edge innovations introduced to his meat business left his competitors scrambling and were met with hostility by other city butchers, leading to both physical brawling and extended court action. [In 1890] Strouse began peddling meat in refrigerated

wagons, selling door to-door to his many customers. More than two hundred San Francisco butchers organized against him, complaining that he was taking all the small cash customers and leaving to the butchers’ shops those … customers who relied on credit to buy their weekly meat. The butchers persuaded the Board of Supervisors to put in a new ordinance, requiring peddlers of meat to buy a license of seventy-five dollars per vehicle every quarter.59

Strouse ignored the ordinance, and on 14 July 1890 had himself arrested to test the law and bring the case to court. According to the San Francisco Call, ‘Strouse had had trouble with the police and some city officials about his license for peddling meat in wagons around town. Strouse claims that an ordinary wagon license is sufficient for his purpose, [and not] the tax people claim that he should pay for a peddler’s privilege.’60 The San Francisco Examiner came out on his side, stating that ‘The case against our enterprising citizen, Mark Strouse … looks more like one of persecution than prosecution. His pre-eminent success over all competitors seems to have caused their envy and malice to the degree of a combine to destroy his business.’61 The persecution tightened on 30 July when a woman named Julia Crowley sued him for $10,000 damages as the result ‘of a serious accident that happened on April 22d last year … when one of his meat trucks ran over Mrs. Crowley and injured her.’62

Strouse refused to be intimidated or to shut down his 14 refrigerator wagons, even while his drivers were being summarily arrested. On 4 March 1891, another delegation of butchers appeared before the licensing committee of the Board of Supervisors demanding that Strouse pay $1650 in licensing fines. While the committee recognized the legitimacy of the debt, it also recognized, as it delicately phrased it, that some ‘difficulty existed in reference to its collection’.63 On 16 May, the city attorney advised the Board of Supervisors that the city ‘cannot recover from Mark Strouse the unpaid license on his meat-peddling wagons’, as Strouse had never taken out a license on them in the first place.64 Then in a suspiciously timed coincidence that profited hundreds of beleaguered butchers, Strouse’s meat packing house on San Bruno and Sixteenth Avenues caught fire and burned down on 10 June at a loss of $60,000.65 Although Strouse lost his case in court the following September, the meat wars dragged on.66 As late as March 1897, the year before his death, he was engaged in battle with the Butchers’ Board of Trade for selling refrigerated meats, a fight that led to a loss of his seat on the board and a place on its blacklist.67

In 1894, during these on-going legal disputes, Strouse sought to boost his profile politically by running for the office of City Assessor. Here again he attempted to outflank his competitors. Through backdoor maneuverings he took the nomination as the People’s Party candidate away from Clarence Ayer, who had already been nominated.68 This effort erupted into another major battle which Ayer pursued without much success in court. Although Strouse won the battle with Ayer, he lost the election. When the votes were tallied on 7 November, the only vote he received was his own.69

Endings

On 30 September 1898, at his residence at 2412 Pacific Street, Mark Strouse died at the age of 53. According to his obituary: ‘His death was not sudden, he having contracted la grippe two weeks ago while selecting meat among the refrigerators.’70 The irony of his death being caused by his refrigerators would not have been lost on those 200 angry butchers who had sued over them for years. Funeral services were held at the Masonic Temple on Montgomery Street with Rabbi Jacob Voorsanger of Temple Emanuel, one of the leading Reform rabbis in the nation, presiding, following which Strouse was buried in the family vault at the Odd Fellows Cemetery.71

Mark Strouse left a significant estate consisting ‘of the homestead, mining claims, real estate, mining stocks, notes, bonds, accounts, a valuable butcher business and other personal property’, all of which was divided between his widow Emilie and his surviving children, his daughter Bertha, and his underage sons, Mark, Jr., and Albert.72 Emilie continued to run Bay City Market for a time but in 1900 she decided to sell. Bertha and Emilie had never liked each other, and Bertha, together with her first husband, William A. Hewitt, sued Emilie to prevent the sale of the market to an outside interest. ‘[A] friendly feeling does not exist,’ reported the San Francisco Chronicle, between the widow and Mrs. Bertha Hewitt, ‘whose mother was Mark Strouse’s first wife … [It was understood that] Mrs. Strouse was to have the sale made as a mere formality and that [Mrs. Hewitt] was to have the market purchased for herself … Judge Troutt declined to order a postponement.’73 Having fallen out with her stepmother and lost the market, Bertha went on to divorce William Hewitt, remarry, obtain a second divorce and die in San Francisco on 16 October 1944 at the age of 68. Emilie Strouse never remarried and died in San Francisco on 21 March 1933.74

*

The Strouse family of Lauterbach was typical of generations of families who came from Europe during the early waves of immigration that followed the discovery of California gold at Sutter’s mill in 1849. As the most financially successful member of the family, Mark Strouse’s life was also typical of the Western experience, rough, brawling, combative, and determined to succeed. He fought back against attacks on his character in Virginia City in 1875 and on his business in San Francisco in the 1890’s, offering no quarter to the attackers. Were these attacks the result of anti-Semitism or personal animosity? It is difficult to tell. Within the world of the Comstock mining camps with their peripatetic populations, Jews were rarely singled out for discriminatory treatment. Where the Chinese, Native Americans and Hispanic peoples were harshly treated as ‘other’, the Jewish community seems to have been generally accepted. From the decisions he made, Strouse’s identity as a Jew on the Comstock became secondary to his economic and social aspirations. Ambitious, aggressive and imaginative, he took risks that allowed him to grow from a penniless 15-year-old German incomer into a wealthy and respected American businessman. His adaptation to his new life was complicated and full of compromise. As a Jew, he was steadfast in his beliefs and loyal to his community even as he chose to marry outside it and specialize in non-kosher products like pork. When he moved to San Francisco, his second marriage and embrace of the American Jewish Reform movement helped him to reassert his place as a Jew. Yet in the end, he chose to be buried not in the Jewish cemetery but in that of the Odd Fellows, a fitting commentary on the complexities and contradictions of his life.

*

NOTES

1 Susan James, Children of the Motherlode, 1856-1926: The Townsend Family and the Growing of the West, Books2 Read, Oklahoma City, OK, 2021, pp. 29-31.

2 History of Nevada and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers, Myron Angel (ed.), Oakland, 1881, p. 570.

3 Heike Zaun Goshen, ‘Destroyed German Synagogues and Communities’, Synagogue Memorial “Beit Ashkenaz”, Jerusalem, 2018. Retrieved from http://germansynagogues.com/index.php/synagogues-and-communities?pid=66&sid=806:lauterbach

4 ‘Lauterbach’, Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities: Germany, vol. 3, Tamir Amit, project coordinator, Jerusalem, 1992. Retrieved from http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/Pinkas_germany/ger3_00220.html

5 History of Nevada, 1881, p. 570.

6 Myra Sauer Ratay, Pioneers of the Ponderosa: How Washoe Valley Rescued the Comstock, Sparks, NV, 1973, p. 13 n 2.

27

7 On a visit to Virginia City in 1882, Strouse was involved in a brawl and fined $10 for assault and battery. Virginia Evening Chronicle, 19 July 1882.

8 Charles Collins, Mercantile guide and directory for Virginia City, Gold Hill, Silver City and American City, 1864-65, San Francisco, 1864-65, p. 200.

9 Territorial Enterprise, 9 August 1876.

10 Territorial Enterprise 15 April 1876.

11 Pacific Coast Business Directory for 1867, Henry Langley (pub.), San Francisco, 1867, p. 311; C. Collins, Mercantile Guide, 1864-65, pp. 222, 227-28.

12 The Virginia and Truckee Railroad Directory for 1873-74, John F. Uhlhorn (comp.), San Francisco, 1873, p. xxii.

13 Territorial Enterprise, 28 October 1877.

14 John P. Marschall, Jews in Nevada: A History, Reno & Las Vegas, 2008, pp. 81-82; Reno Gazette-Journal, 29 April 2014. Retrieved from http://www.rgj.com/story/life/2014/04/30/nevada-nuggets-kosher-meat-market/8492235/

15 Unattributed, ‘Mokelumne Hill Cemetery Project, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.calaverashistory.org/mokelumne-hill-cemetery

16 Territorial Enterprise, 24 February 1878.

17 Mary McNair Mathews, Ten Years in Nevada: Life on the Pacific Coast, Buffalo, 1880, p. 165.

18 San Francisco Call, 1 October 1898.

19 Oscar T. Shuck, San Francisco, San Francisco, 1897, p. 171; San Francisco Call, 19 December 1897.

28

20 The Pacific Coast Business Directory for 1876-78, 1875, p. 612; U. S. Federal Census, Virginia City, Storey County, Nevada, 1900, p. 14; Territorial Enterprise, 9 December 1874.

21 Weekly Alta California (San Francisco), 17 June 1871.

22 Carl Stoddard & J. A. Carpenter, ‘Mineral Resources of Storey and Lyon Counties’, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, 49, 1950. Retrieved from http://www.westernmininghistory.com/mine_detail/10043933

23 Gold Hill Daily News, 4 May 1872; Yerington Times, 7 February 1875.

24 Territorial Enterprise, 19 August 1874, 29 November 1876, 9 November 1877 & 6 November 1879.

25 Territorial Enterprise, 18 September 1874; Daily Stock Report (San Francisco), 4 June 1875; United States annual mining review and stock ledger … for the year 1879, New York, p. 232.

26 History of Nevada, 1881, p. 570.

27 Sacramento Daily Union, 5 June 1868.

28 Gold Hill Daily News, 1 October 1868.

29 Gold Hill Daily News, 2 June 1868.

30 Reno Gazette-Journal, 15 August 1878.

31 Topeka Daily Capital, 31 May 1883.

32 History of Nevada, 1881, p. 584.

33 Reno Gazette-Journal, 18 August 1878.

29

34 Marriage Book of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Virginia City, 1873, vol. 2, p. 298; Marriage Records, County Courthouse, Virginia City, Storey County, vol. A, p. 276; San Francisco Chronicle, 21 January 1874.

35 Alfred Doten, The Journals of Alfred Doten, 1849-1903, Walter Van Tilburg Clark (ed.), Reno, 1973, p. 1217.

36 Gold Hill Evening News, 15 January 1874.

37 Harry M. Gorham, My Memories of the Comstock, Los Angeles, San Francisco & New York, 1939, pp. 131-32.

38 Sacramento Daily Union, 28 October 1875.

39 Owyhee Daily Avalanche (Silver City, Idaho), 27 October 1875.

40 U. S. Federal Census, Virginia City, Storey County, Nevada, 1880, p. 6.

41 U. S. Federal Census, Virginia City, Storey County, Nevada, 1880, p. 33; Storey County Death Records, Vol. B, p. 66.

42 San Francisco Weekly Stock Report and California Street Journal, 5 November 1875.

43 Territorial Enterprise, 13 September 1876.

44 Territorial Enterprise, 6 & 7 September 1877.

45 Storey County Courthouse, Virginia City, Nevada, Strouse Divorce Papers, 1878.

46 Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada), 16 August 1878.

47 Reno Gazette-Journal, 19 December 1878.

48 Nevada State Journal, 7 December 1880.

49 San Francisco Examiner, 7 December 1880.

50 Nevada Death Records, 1911-1965, #17-000364 (1 April 1917).

30

51 U. S. Federal Census, Virginia City, Storey County, Nevada, 1880, p. 46.

52 Territorial Enterprise, 15 November 1879.

53 Territorial Enterprise, 1 March 1881.

54 Salt Lake Tribune, 10 September 1881.

55 U. S. Federal Census, Mokelumne Hill, Calaveras County, California, 1860, p. 13; U. S. Federal Census, 6th Ward, City of San Francisco, California, 1870, p. 135.

56 San Francisco Examiner, 23 December 1893.

57 Erica J. Peters, San Francisco: A Food Biography, Walnut Creek, CA, 2013, p. 91.

58 The San Francisco Call, 27 December 1896.

59 E. Peters, San Francisco, 2013, p. 91.

60 San Francisco Call, 15 July 1890.

61 San Francisco Examiner, 2 July 1890.

62 San Francisco Call, 30 July 1890.

63 San Francisco Chronicle, 5 March 1891.

64 San Francisco Call, 16 May 1891.

65 San Francisco Call, 11 June 1891.

66 San Francisco Chronicle, 28 September 1890.

67 San Francisco Examiner, 23 March 1897.

68 San Francisco Call, 18 October 1894.

69 San Francisco Call, 7 November 1894.

70 San Francisco Call, 1 October 1898.

71 San Francisco Call, 3 October 1898.

72 San Francisco Call, 14 October 1898.

31

73 San Francisco Chronicle, 30 October 1900.

74 Los Angeles Times, 21 March 1933.

*

Susan E. James, Ph.D, is an independent writer and researcher. She is the author of four books specializing in English history,