Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Chapter 23, Exit 15B (B Street): Copley Symphony Hall

From left branch of B Street Exit (15B), turn left from bottom of offramp to B Street and follow to building at northwest corner of B and 8th Street. Copley Symphony Hall is located at 750 B Street

Violinist Eileen Wingard was never the star of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra. Such billings belong to conductors like Zoltan Rozsnyai, Peter Eros, David Atherton, Yoav Talmi, and Jung-Ho Pak, all of whom she played under during a career stretching from 1967 through 2004.

Violinist Eileen Wingard was never the star of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra. Such billings belong to conductors like Zoltan Rozsnyai, Peter Eros, David Atherton, Yoav Talmi, and Jung-Ho Pak, all of whom she played under during a career stretching from 1967 through 2004.

Or perhaps the stars are donors like Irwin and Joan Jacobs, who in 2002 gave the San Diego Symphony an amazing gift of $120 million, the largest ever given to an orchestra in America.

Maybe that kind of accolade belong to such Jewish colleagues whom Wingard admired over her time with the symphony as violinists Otto Feld, Angela Homnick and Beth Farkas, violist Dorothy Zeavin, cellists Marcia Bookstein, Richard Levine, Ron Robboy and Carla Holland-Moritz, bassists Peter Rofe and John Greene, clarinetist Marian Liebowitz, trumpet Mark Bedell, French horn Daniel Katzen and harpist Sheila Sterling.

Does Eileen rate herself with this group? Oh no. She is far too modest about herself and her career. She is the type of person who, if she were the guest of honor at a big banquet, would stay afterwards to help clean up. She prefers to give praise than to be praised. In her 90’s at the time of this writing, her greatest loves—in addition to her talented family members—continue to be playing the violin, teaching others to play violin, and educating people about classical and Jewish music.

After I realized that Copley Symphony Hall at the Jacobs Music Center was a quick jog from the B Street offramp, I coaxed Eileen into giving me an interview about her life and career. Wingard is not only a retired symphony musician but also is an important force in bringing Jewish music and culture to the San Diego community. I might never have persuaded her – given her innate modesty – except for the fact that we have had a continuing professional relationship; I as the former editor and publisher of San Diego Jewish World, and she as the talented and perceptive music reviewer for that online publication.

After I realized that Copley Symphony Hall at the Jacobs Music Center was a quick jog from the B Street offramp, I coaxed Eileen into giving me an interview about her life and career. Wingard is not only a retired symphony musician but also is an important force in bringing Jewish music and culture to the San Diego community. I might never have persuaded her – given her innate modesty – except for the fact that we have had a continuing professional relationship; I as the former editor and publisher of San Diego Jewish World, and she as the talented and perceptive music reviewer for that online publication.

Our interview started at the beginning, covering how she was first exposed to music and how she progressed to become a professional musician. It then worked its way through her observations about SDSO conductors whose eyes she looked into over her music stand. Finally, we discussed her groundbreaking work as head of the music committee of the Jewish Community Center, now demolished, that once occupied a stretch of 54th Street north of University Avenue.

Born Dec. 3, 1929, Eileen lived in a crowded, working-class neighborhood of Chicago, where four generations of her maternal (Markin) family lived. She occupied the flat with a great-grandmother, grandparents, a pair of uncles, an aunt, her parents as their “spoiled and indulged” only child (as of then). Somehow, the family managed to find room for an upright piano, upon which she learned as a young child how to play “The Merry Widow Waltz” composed by Franz Lehar.

At the age of nine, she moved with her parents to the City Terrace section of Los Angeles, where her parents “couldn’t afford a piano.” The following year, Eileen’s mother’s first cousin Annarita Uretsky came to live with them. She was from Great Falls, Montana. Cousin Annarita gave Eileen her first violin lessons. “When she gave up her students, she gave them all, 13 of them, to a man named Karl Moldrem. He was the founder of the Hollywood Baby Orchestra. Because Annarita gave Karl Moldrem her 13 students, she asked him to teach me on scholarship, which he did.”

In junior high school, Eileen became the assistant concert master and later concert master of the school’s orchestra. In high school, whenever she could, she played in “rehearsal orchestras” – those that play together but never perform. At age 16, she landed a receptionist’s job at the Schirmer Music Store, the place where Modrem had been giving her lessons. Next, she received a scholarship from the Parent-Teachers Association to study under Heimann Weinstine, who was the assistant concert master of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. At age 18, with the help of luthier Ben Koodlich, she obtained an 18th century Italian violin believed to have been crafted by Pietro Antonio Landolfi, which she continues to play today.

Eileen’s life continued on a musical trajectory. As a music major at UCLA and a member of the Mu Phi Epsilon music sorority, she had the opportunity to play for Richard Lert, the conductor of the Pasadena Symphony. He promptly hired her in 1950 as a violinist in the orchestra, while she was still attending UCLA.

“He was one of the greatest musicians, especially with Beethoven and all the German composers,” Eileen recalled. “However, because it was a non-union orchestra, even though I was hired as a union member, he could keep us for dress rehearsals to midnight. We had one week of rehearsals leading up to each concert, and then the night before, we would be up to midnight. All that has changed, because there are all kinds of strict union laws.”

She continued with the Pasadena Symphony as a young woman married to language educator Hal Wingard. After they both received their teaching credentials, Eileen began her junior high school teaching career, teaching music at John Adams Junior High School and later at John Burroughs Junior High School. In the latter school, she had some youngsters with tremendous talent, none more so than Leonard Slatkin, a violinist, who would rise to become the conductor of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and later of the National Symphony in Washington D.C., and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Recordings of orchestras that performed under his baton won for Slatkin six Grammy awards and 35 nominations before he completed his assignment in Detroit. He also was awarded the National Medal of the Arts. He never forgot his junior high school teacher, sending Eileen a congratulatory note on her 90th birthday celebration in 2019

As a music student, “you can practice and have lessons and read literature, but to learn the elements of playing in an orchestra, those are added skills,” Eileen told me. “You have to learn how to watch the conductor; how to watch your principal in your section and how to blend in your sound with everyone else’s, and how to not bump into your stand partner. There are all kinds of little tricks that you learn, and how to play seated. Most private lessons you are standing with the violin.”

When their first daughter Myla was approximately 18 months old, Hal and Eileen both won Fulbright scholarships to study in Germany. Eileen’s was to study violin at the Hochschule fuer Musik in Stuttgart while Hal served as an exchange professor at the gymnasium in the medieval town of Tauberbischofsheim in the northeast of Baden-Wurttemberg.

Eileen returned to the Pasadena Symphony until a career opportunity for Hal prompted the family to move to San Diego in 1966. A year later, she had an eventful audition for the symphony, which at that time performed in the San Diego Civic Center at 3rd and B Street, in the venue still used by the San Diego Opera.

Discussing her preparation for the audition, Eileen noted, “I am not a good sight reader, so I made some educated guesses. I saw that they had Beethoven’s ‘Eroica Symphony’ on the program, so I got the music of the first violin and I learned it very well. And I was right; they did give me Beethoven’s ‘Eroica Symphony’ to sight read, only it wasn’t sight reading. I knew they would also ask me something by Richard Strauss, one of his tone poems. Usually it is ‘Don Juan’ and I prepared ‘Don Juan’ very well, but instead they asked for ‘Til Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks’, and I wasn’t able to figure out all those high notes too well. Thus, I got into the San Diego Symphony in the second violin section.”

Eileen explained that the second violin section “usually plays at a lower pitch, so it is often not as demanding as the first violins which often have to go way up high and read notes with many ledger lines, so they are harder to discern and they are harder to play.”

Her first conductor was Zoltan Rozsnyai, who previously had led the Hungarian Orchestra in Austria, after he and other refugees fled there in 1956 after Soviet forces crushed an unsuccessful Hungarian revolution.

“Rozsnyai was a warm, good musician but some of the people in the orchestra didn’t fully understand him because of his accent,” Eileen recalled. “He sometimes didn’t speak loudly enough, and he had some communication problems. He had his finger in so many pies. He started the music department at [the now defunct] United States International University, which took in a lot of Chinese students, and he was writing for Hollywood movies. He did composing. One rehearsal, he forgot about and didn’t show up. The assistant conductor, Bud Emile, took over and from then on it was Rozsnyai’s downfall. There was a petition signed by the orchestra members. He lasted four years. During that time, it was like two steps forward, one step back. In my first season, we were supposed to have 12 concerts and it was pushed back to eight. The summer season was canceled, and there were always financial problems.”

(Melvin G. Goldzband, a psychiatrist who served on the orchestra’s board of directors, detailed the symphony’s dire economic condition in his book From Overture to Encore. The subsequent record-breaking contributions by Irwin and Joan Jacobs resolved the financial crisis.)

After a series of guest conductors auditioned for the job, another Hungarian, Peter Eros, was appointed in 1972 as the next conductor.

“He was well-organized and well-prepared unlike Rozsnyai,” Eileen informed. “He knew what he wanted. He got wonderful soloists and he is the one who made the orchestra go further than anyone else by changing us from a night-time rehearsal orchestra, like a regional orchestra, to a major orchestra by having rehearsals at daytime and having us on a professional footing.”

She recalled that “instead of looking at the musicians into the eye, he would often look up as if he were in his own world, trying to achieve what he dreamed it ought to be. And there was something very magical about watching his blue eyes as he conducted. … He got the brass to play a beautiful, rounded tone so that they never blasted. Their balance was always excellent with the other sections and that was another of his outstanding traits.”

Eros completed his tenure in 1980, going on to teach at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland, and then on to conducting positions in Denmark, Scotland, England, and Sweden before settling into a teaching position at the University of Washington in Seattle. “His orchestra concerts were so good, and with his wonderful sense of humor, the kids adored him,” said Eileen, who socialized with Eros and his family. “He even had the critics coming to review his university symphony concerts and he taught a few good conductors who have orchestras of their own now.”

Again there was an interim period when various guest conductors auditioned with the orchestra until David Atherton was selected late in 1980. Atherton, like Eros, “was a very witty guy.”

“Whereas Eros would always like music to move ahead and go somewhere, David was much more a strict disciplinarian and I remember playing Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite of Spring.’ He made it easy because he was so strict with the meter and the tempo and he showed us how the meters changed so well. I really appreciated playing that piece under him. He was a good conductor, but I also remember him saying something that was really derogatory. We had a performance in National City and there was a Mexican woman who brought a young child and the child started to cry, and he (Atherton) turned around and said something derogatory like ‘why don’t you go back to where you came from?’

Eileen’s next conductor was Yoav Talmi of Israel. Eileen shared a close friendship with him and his wife Er’ella. “We had a brunch for him to welcome him,” she remembered. “He was a very poetic conductor. He was the only conductor who never re-seated anyone. He felt that he needed to bring up the level of all the players and inspire them to work harder and be their very best. He did not want to re-seat anybody or fire anybody. He was very collegial. He was warm and open to all the musicians. He would look at people and his beautiful eyes communicated what he wanted. He had blue eyes, but they were shaded in dark lashes, and he had a dark complexion, so it was very special looking at Talmi and he got some excellent performances out of us.

“Under Talmi we did about eight professional recordings and you can still hear them today; they are a beautiful testament to the high degree of musicianship and to the wonderful quality that the orchestra had attained then … I became friends with the Talmis; I had them over. When he had Zina (Schiff, her sister, a violin soloist) perform, I had a reception at my house afterwards. I got to know his daughter Dana, his son Gil and, in fact we had Er’ella play chamber music at the Jewish Community Center when I was the music committee chair there.”

During five years of Talmi’s reign, Eileen served as the coordinator for pre-concert lectures for the symphony. She recruited fellow symphony musicians “who I knew were good presenters and faculty members from the music faculties from various universities. These lectures would be given an hour before the actual concerts – first in the lobby, and then later they got moved into the main hall, just as it is today.” Eileen recruited Nuvi Mehta, who subsequently became the principal lecturer

At the end of Talmi’s era, the San Diego Symphony Orchestra was overwhelmed with its recurring financial difficulties. “We went bankrupt, and I am still bitter about that,” Eileen said. ‘I remember our last concert when we did Mahler’s ‘Resurrection Symphony’ in the hope that we cold resurrect the symphony … I remember musicians coming out of that symphony in tears.”

San Diego Symphony Orchestra struggled out of bankruptcy, much to the credit of attorney Herb Solomon, who took over the presidency of the board. Jung-Ho Pak, who had been Talmi’s assistant, took over the orchestra for two years as it struggled back to its financial feet. Next, with the security of the large donation from the Jacobs family, Jahja Ling was appointed as conductor.

It was at that point that Eileen retired from the orchestra because her mother, Rose Schiff, needed care, and her husband, Hal, was in declining health. Both have since died.

For an orchestra player like Eileen, accompanying well-known concert soloists like pianists Van Cliburn, Vladimir Horowitz, and Arthur Rubinstein and violinists like Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern, Itchak Perlman, Pinchas Zuckerman and Henry Szerling was a particular thrill. She would ask such stars to autograph the jackets of their records or CDs.

“Most thrilling of all were the times that I got to play in the orchestra accompanying my own sister, Zina Schiff,” Eileen commented. “Her first appearance was at the closing Tchaikovsky summer concert in 1969, when as a teenager she played the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto under Roznayai. The next December, she played the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto under the assistant conductor, Robert Emile. The first season Peter Eros took over, the orchestra played a special concert sponsored by Wells Fargo Bank and Zina was soloist in the Mendelssohn again. During Atherton’s leadership, Zina played the Ernest Bloch Violin Concerto under the assistant conductor, Matthew Garbutt. She played the Barber Violin Concerto under Talmi, and finally played the Rhapsody Hebraique by Richard Nanes under Jung-Ho Pak.”

Eileen may be her younger sister’s biggest fan. I asked her why she considers Ziva so much more talented than herself as a violinist?

“She was born with a natural talent, and she also has a marvelous memory,” Eileen responded. “I have never heard her make an error in her performances and she plays with great feeling and musicality.” In contrast, Eileen several days before our interview played violin for a five-minute video about Russia’s Jewish Folksong Society and “I had to work and work and work. I know what I want and how I would like it to sound, but to get it there, it takes a lot of careful practice. Zina gets these things rapidly and instinctively, as one critic said, it is like a fish in water. In person, she comes off a little on the shy side but when she is on stage playing her violin, she is in her glory. That is the difference. I still have to take deep breaths and be very aware of trying to be calm when I play. And for her, it is second nature.”

Besides accompanying her sister, Eileen also has had the pleasure of having her daughter play with her in the orchestra. She recalled, “During two summers when Myla was at UCSD, studying violin with Rafael Durian, she substituted in the San Diego Symphony. I was delighted to have my daughter as a colleague in the orchestra and proud of how she held her own along the other professional violinists.

When it comes to arranging musical and other cultural events, Eileen clearly is first chair. At the old 54th Street JCC, “we developed programs for kids for Chanukah, Purim and Pesach.” Yale Strom, today a renown klezmer musician and ethnomusicologist, played in the programs with two siblings, and Eileen’s own children performed. Eileen’s son, Dan, was on the cello, Myla and Harriet on violins and Tami on flute. “I gathered them all together and made a simple arrangement of the holiday music.”

Additionally, “the JCC Music Committee had a concert series – mostly chamber music – in which we would recruit symphony musicians and others of professional quality who would give beautiful programs. Actually, these musicians would apply to us to be presented. If we heard someone from Israel was here like Yossi Arnheim …and might want to play, we would arrange a concert. How we financed these, we simply shared the profits with them. We didn’t make any budget; we didn’t prearrange any sum at first, but simply did our best publicizing the event, so there would be income. We would give them half or even more than half if we could. So, we had a lovely series.”

Eileen remembered, “When piano virtuoso and pedagogue Ignace Hilsberg [brother of Alexander, former conductor of the New Orleans Symphony] came to San Diego, I got in touch with him, and he was willing to get involved with the JCC Music Committee. He helped us select our piano, the nine-foot Baldwin Grand, which is at Tifereth Israel Synagogue and continues to be used for performances of TICO (The Tifereth Israel Community Orchestra, conducted by David Amos). He, himself, played at a fundraising concert and later, he brought some of his outstanding friends like violinist Louis Kaufman and his wife, Annette, an excellent pianist. Louis Kaufman was concertmaster of some of the Hollywood movie orchestras. He played the solo in Gone With the Wind and he made at the time more recordings than even [violinist Jascha] Heifetz. Anyway, they gave concerts, and we paid them what our income was.”

TICO had started as the JCC Orchestra. Eileen, as chair of the JCC’s music committee, participated in the initial meeting between conductor David Amos and Joe Astor, the JCC’s executive director. “I was one of the people who tried to convince Joe that we ought to have an orchestra there,” Eileen said. “And I played in it for a while. First, it was a chamber orchestra and I played viola in it. Then it got to be too much for me with the Symphony, but when the Symphony didn’t play during the year that we were in lockout with Atherton, I played in the JCC Orchestra.”

The 54th Street JCC moved to its present location in La Jolla, where it is now known as the Lawrence Family JCC, Jacobs Family Campus. Eileen became active in its Music Festival Committee, arranging a concert featuring the music and performances of Yoav and Er’ella Talmi, and three others featuring her sister Zina, who then lived in Tiburon, California.

I suggested that music education was perhaps an even greater love for Eileen than playing.

“Well, as great,” she responded. “Once I retired, I started giving monthly talks at the Jewish Family Service [senior] center on College Avenue and the one in Poway. I also gave one at the University of San Diego, and another for Elderhostel at the Brandeis Bardin Institute (in Simi Valley). Then unfortunately in 2007, I had a heart attack and I had to cut back on a lot of that.”

“Well, as great,” she responded. “Once I retired, I started giving monthly talks at the Jewish Family Service [senior] center on College Avenue and the one in Poway. I also gave one at the University of San Diego, and another for Elderhostel at the Brandeis Bardin Institute (in Simi Valley). Then unfortunately in 2007, I had a heart attack and I had to cut back on a lot of that.”

Cut back? Don’t believe it. Eileen is still giving lectures, such as one at the 2021 ‘Tapestry’ event sponsored by the JCC. She covers and reviews classical music productions for San Diego Jewish World. Additionally, she is giving private violin lessons. You try doing all that in your 90’s.

*

Next Sunday, June 12, 2022: Exit 15B (B Street): San Diego City Administration Building

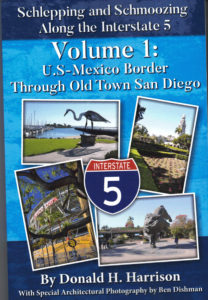

This story is copyrighted (c) 2022 by Donald H. Harrison, editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. It is an updated serialization of his book Schlepping and Schmoozing Along Interstate 5, Volume 1, available on Amazon. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Wonderful article, chapter, and tribute to a very special and beloved lady. Congratulations, Eileen!