Chapter 28, Exit 17B (Sassafras Street): San Diego Unified Port District

Chapter 28, Exit 17B (Sassafras Street): San Diego Unified Port District

From Sassafras Street exit, turn left and follow it to a right on Pacific Highway to large Port of San Diego building on the left at 3165 Pacific Highway. Make the soonest possible U-Turn to arrive at its parking lot

The San Diego Unified Port Commission headquarters is the gathering place for representatives of the five cities that front on San Diego Bay. They are San Diego, Coronado, National City, Chula Vista, and Imperial Beach. Besides being responsible for maritime operations – such as the coming and goings of cargo and passenger ships—the Port also is the landlord for businesses and public accommodations located on the tidelands surrounding the bay. Its seven commissioners are important and powerful land-use decision makers. The Port District shares jurisdiction with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps over bayfront property. In 2003 the state Legislature and governor transferred responsibility over the San Diego International Airport from the Port District to a separate airport authority.

Members of the Jewish community who have served on the Port Commission since its creation in 1962 were Harvey Furgatch (appointed 1969), Milton “Mickey” Fredman (1970), Ben Cohen (1977) and Louis Wolfsheimer (1979), all of whom had passed away prior to my undertaking this book, and Robert Penner (1988), Lynn Schenk (1990), Stephen Cushman (1998) and Laurie Black (2007), all of whom I had the opportunity to interview. All these Jewish Port Commissioners represented the City of San Diego, except for Penner and Cohen, who were appointed by Chula Vista and Coronado respectively.

With San Diego represented by three commissioners and the other four cities represented by one commissioner each, even if San Diego appointees are agreed on some proposal, they cannot push through their agenda without the cooperation of at least one commissioner from another city. If the four smaller cities band together, they can outvote San Diego. This system puts a premium on cooperation among the five Bay cities.

Rivalry among the cities is not the only set of competing interests with which port commissioners must deal. Politics has been defined as a system for the allocation of scarce resources. Nowhere is this truer than at the Port District where there are many kinds of interests, including tourist, environmental, industrial, retail, recreational, cultural, and maritime, just to name a few. They compete for the use of land around the irregularly shaped, 19-square-mile bay that at its longest measures 12 miles and at its widest 3 miles.

Dr. Robert Penner

Dr. Robert Penner, an ophthalmologist who also was a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, was appointed to the Port Commission in 1988. He previously served in the presidencies of the San Diego County Opthalmology Society in 1973, the San Diego County Eye Bank in 1977, and the San Diego County Medical Society in 1986.

“I learned what running a meeting is like,” Penner told me. “There are real skills in running a meeting. The secret is let everyone at that meeting know that ‘you have been heard.’ If you were coming before the Port, or any official body, and you make a presentation, you are feeling very strongly about something that is happening in your backyard. You know this backyard and you want to tell this agency that you know what you are talking about and if they don’t agree with you, it is because they didn’t hear you. Because if they heard you and listened to you, they would agree with you! So, I brought those two skills to the Port; the ability to listen and when it came time, running the meeting efficiently and empathetically.”

The process by which Penner was appointed involved members of the Chula Vista City Council narrowing down their choices on three rounds of balloting. On February 20, 1988, the council had 14 applicants for Port Commissioner to consider. Then-Mayor Greg Cox suggested that he and fellow council members each voted for five applicants, allowing any applicant who received more than two votes to continue to the next round. Penner, with four votes, was one of six applicants who made it to round two. For that round, Mayor Cox instructed the council to vote for three applicants and those receiving three votes or more would survive to a third ballot. Penner was one of four survivors. On the final third ballot, Cox told his fellow councilmembers to vote for just one applicant. Penner received three votes, two other candidates received one vote each, and a fourth candidate received zero votes. Thereupon a motion was made to appoint Penner, which was approved on a vote of 3-2, with Mayor Cox in the minority.

Fellow Port commissioners recognized Penner’s leadership skills by electing Penner to serve as their vice chairman in 1990 and as chairman in 1991.

“When I got on, I didn’t know about the multidimensions of the Port; what it did for the city, what it did for the community,” he reflected. “I had no real idea. You learn fast enough, but since I didn’t know, I quietly asked some of the staff. I said, ‘I’m going to be here for four plus years, what would be a good thing for the Port to have?’ There was no cold-storage facility that was on the docks south of Port Hueneme. The reason for having it on the docks is to reduce the number of times you have to move a perishable commodity. The staff person said we and the San Diego area could use that and we are a natural for it because we are the closest U.S. west coast port to South America. Not only that but our growing season is opposite, so we are not in competition with South America. If we could build a cold-storage facility, that would be a great contribution to the all-year availability of delicate fruits while utilizing underutilized space at the Port of San Diego that didn’t need container crane capability to move the cargo.”

It cost approximately $10 million to build the cold-storage facility at the Tenth Street Terminal, and “there were other people who didn’t necessarily feel that was the right project or in their interests. It had nothing to do with Chula Vista. This was an example of when you raise your hand and you swear allegiance to the Port of San Diego and the people of the State of California, not to your city. And that requires you to say that there are times when you are not going to vote for something the people in your city might particularly want at any particular time. You have to want to do the job more than you want to be reappointed. That is very important.”

Each year for five years, Penner flew to South America, calling on growers in Chile, Argentina, and Ecuador to interest them in shipping their produce to San Diego. Eventually, the Port landed the contract with Dole for the storage of millions of bananas here. Bananas and stone fruit from South America constitute the bulk of the business utilizing the cold-storage facility.

“We (the Port of San Diego) built it by ourselves,” Penner said. “The effect on the region was much more than any money it brought to the Port. It’s that multiplier effect. If you could actually see the flow of money that comes in as a result of an enterprise spurred by you as an agency—if the people could see it—they would think differently about what is going on. There was an entrepreneur in Chula Vista who knew that—Fred Rohr. He paid everyone in silver dollars one pay day. That made everybody aware of the flow of money that was coming from Rohr. That was genius!”

Penner noted that during his time on the Port, the San Diego Convention Center was being developed at its present location on Harbor Drive. One of the Port Commissioners at the time was Bill Rick, president of Rick Engineering, who helped Port Commissioners understand the nuances of the construction process.

“There were, of course, members of the Port Commission who were attorneys who, at times, provided insight into the legal ramifications of what was being proposed,” Penner commented. “The Port Commissioners who were in finance and business helped the rest understand the financial ramifications of certain Port decisions. There were not very many ophthalmologic issues, but I remember very well the controversy surrounding the effort to stop tobacco smoking at the airport (at that time administered by the Port.). In the end it enriches the Port and therefore the general community to have ‘lay’ members as Port Commissioners.”

Two years into Penner’s term, on January 23, 1990, attorney Lynn Schenk was appointed by the San Diego City Council to the Port Commission, filling Louis Wolfsheimer’s unexpired term ending January 2, 1991. Thereafter she was reappointed to the post, in which she stayed until January 5, 1993, the day she was sworn in as a member of the U.S. Congress.

Lynn Schenk

Although Schenk is a Democrat, her appointment came with the encouragement of San Diego City Councilwoman Abbe Wolfsheimer, a liberal Republican, whose first husband’s resignation from his Port Commission seat created a vacancy. At the time, no Democrat was serving on the technically non-partisan Port Commission and, according to Schenk, Councilwoman Wolfsheimer told her: “We have to have you on the Port. You’re a woman. You’re a Democrat. You have a different perspective.” However, the Democrats sitting on the City Council were backing Joe Francis, head of the San Diego & Imperial Counties Labor Council, for the seat, while Republicans were divided in their choices. With Mayor Maureen O’Connor, a Democrat and a former Port Commissioner, absent that day, the eventual winner needed to get 5 votes from the remaining 8 members of the Council. Put another way, that person must not have more than three votes in opposition to his or her candidacy. Schenk started off with firm opposition from two Democrats: Bob Filner, a fellow Jew, and John Hartley who reportedly was told by the Hotel del Coronado’s Jewish owner M. Larry Lawrence that he’d feel betrayed if Hartley voted for Schenk. Lawrence said it would be like “a knife in my back.”

No candidate received a majority on the first ballot. Schenk’s husband, attorney C. Hugh Friedman, persuaded Councilman Ron Roberts to vote for Schenk on the second ballot, and with friendship, “Ron’s for Hugh, and Abbe’s for me,” enough votes were cobbled together to put Schenk over the top. For a second seat on the Port Commission, the City Council voted unanimously for Cliff Graves, a Republican. Both appointees were firsts: Graves, an African-American, and Schenk, a Jewish woman.

Before she took office, Schenk remembers being counseled by her husband, a lawyer who was a leader of many boards and commissions, including the 22nd Agricultural District (Del Mar Fair) Board, the State Board of Education, the San Diego County Bar, and the county’s Civil Service Commission. “He said to me, ‘Lynn, please listen to me for a change. Go to a couple of meetings. Don’t say anything. Just listen. You keep saying you don’t know much about the Port, so listen, and learn, and then you can start to see what areas interest you.’ I knew that the environment interested me and the issue of the Bay and its pollution, but I said, ‘That’s good advice; I’ll do that.’

“So, I go to my first meeting, and I am sitting next to the representative from Coronado, a wonderful man, Admiral Raymond Burk. What a gentleman! He welcomed me. I will say a couple of the others were not so welcoming. Bob Penner welcomed me … There were a couple of items on the agenda. A man by name of Eliseo Medina came to the podium. He was the head of SEIU (Service Employees International Union). … This man, had he been born here, could have vied for President of the United States. I so admire him. Two or three meetings before I came on the Board, the Port Commission had decided to subcontract the janitorial service at the airport to an outside contractor. What this outside contractor did to this day breaks my heart. He immediately fired all the janitors who had been Port employees, who in the deal were made employees of the subcontractor. Eliseo was there to plead with the Commission to reconsider this issue because they had just summarily fired everybody. I couldn’t believe it.

“I said, ‘I have to ask some questions. Were these people interviewed to see their competence to be kept on – the normal kind of thing that you would do as a new employer taking over another company or in this case a contract?’ No, he just sent out a notice to every one of them that they were fired – a drive-by firing.” Schenk made a motion to grant reconsideration – that is to schedule another vote on the issue. Her motion was defeated, but Schenk did not give up.

Having learned that the same organization once had a contract with the San Francisco Airport, but lost it because they had many problems there, Schenk telephoned the California Secretary of State’s office for a copy of the company’s articles of incorporation. Although the representative of the contractor said that the executives involved in San Francisco all had been replaced, the articles of incorporation proved otherwise. Without telling him what she had found out, “I called Admiral Burk and I said, ‘I’ve gotten some new information and I would really like to have a reconsideration.’ He said, ‘If you make the motion, I will second it.’” Likewise, ‘I called Bob Penner and Cliff Graves, so there were enough to bring it back for reconsideration.

“We had the contractor there and we had Eliseo there. I did a little cross-examination, and the contractor said, ‘No, no, these are all new people.’ And I asked, ‘Is your name so-and-so?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, here are the articles of incorporation. Is this your signature?’ He almost plotzed. He almost fell over. He never thought that someone would find out that it was the same company. There was no rachmanis, no feeling for the people who keep the airport toilets clean for you. To just summarily drive by and fire them and hire people at a much lower wage with no benefits—I couldn’t keep my mouth shut about that.

“I made the motion to rescind the contract, to rehire all the janitors, and start anew, so they knew if we’d subcontract it again, they’d understand that the people who are already there should have an opportunity to continue to work. The motion passed with all but one person voting for it, 6-1. I considered that to be one of my greatest accomplishments early on. I get a little teary when I recall the expression of appreciation by the janitors. I showed up at the airport one day – I don’t remember where I was going, maybe Sacramento – and they were there with signs thanking me for saving their livelihoods. It was very special.”

While that come-from-behind victory may have been Schenk’s most dramatic episode on the Port, she said she also took satisfaction in her successful effort to create an environmental subcommittee of the board, which included Penner and Milford W. Portwood of Imperial Beach. “I worked with the staff on the first-ever environmental report by the Port. I had consultants working with me on ‘Five Year Action Plan for a Clean San Diego Bay’ in 1992 to clean up and mitigate the state lands around the bay that were under the purview of the Port. I took that issue to Congress with me. We weren’t able to do a whole lot, but we were at least able to get the sewage treatment plant in Pt. Loma.”

Another battle, in which she didn’t fare as well, was over funding for the America’s Cup races off the coast of Pt. Loma. “This was a lesson for me about hypocrisy,” she told me. “The very same members of the commission who did not want to spend money on environmental issues wanted to spend a lot of money on the America’s Cup. The America’s Cup committee members made a proposal to the Port for financial support, and I will never forget that they had a very slick brochure, beautiful. It had pictures of Dennis Conner [who had won the America’s Cup in 1987, bringing it back to San Diego from Australia], the ‘Stars and Stripes’ boat; a great picture of the first President Bush, a great picture of the American flag, and no numbers, just the bottom line of what they were asking for. So, here I am, supposedly the liberal Democrat, asking about the numbers. ‘How is this going to be spent? What is the total budget? What percent of the budget are you coming to us for? How does this benefit the Port cities?’

“One of the commissioners looked at me across the horseshoe dais – I was at one end, and he was at the other, sitting next to Bob Penner – and he became so angry with me. ‘How dare you ask these questions? Do you know who is backing this?’ Then he listed a bunch of very important people in San Diego who are backing this and indicated, ‘You just have to take their word for it that this is going to be a benefit.’ I wouldn’t. I said, ‘I support some funding for the America’s Cup, but I need to know more information.’ And we never got it. As I recall, I voted no, but I was the only ‘no’ vote. It troubled me, this boosterism. As fun as the America’s Cup is, and San Diego thought it was so important, but you know, we had a fiduciary duty to the state and to the public about how the money was spent, but apparently not on this. We had to take it on faith! But everything else, they drilled down to the penny, especially the environmental stuff.”

In other initiatives, Schenk said she pressed Port Director Don Nay to hire more women on the staff, “and we made progress there.” Additionally, “I was very interested – not my lead issue, but I was very interested, in expanding the Port for commercial purposes. We had a good chance of becoming the overflow port for cars that were imported. We made a lot of progress there, though that wasn’t just me, that was the Port commissioners as a whole.”

Stephen Cushman

Of the four Jewish former port commissioners I interviewed, Stephen Cushman served the longest, 12 years, having been appointed in 2006 to an uncharacteristic third term by the San Diego City Council with backing from organized Labor and from environmentalists. Cushman’s family owns Grossmont Center and the Riverwalk golf course in Mission Valley. Both stretches of land were inheritances from Cushman’s great-grandfather, Adolph Levi, an early Jewish settler who came to San Diego in 1860. Cushman also had owned several car dealerships.

A business-oriented Republican, Cushman’s third-term victory came over Democratic activist Laurie Black, who a year later joined Cushman on the Port Commission. Labor leaders appreciated Cushman, who previously had served as board chairman of the San Diego Convention Center, in part because he had pushed successfully to attract a union hotel to be constructed near the Convention Center. The 1190-room Hilton San Diego Bayfront was important to attract, Cushman told me, because “there are 50,000 delegates a year in the United States who will only go to a convention center that is union.” He and Jerry Butkiewicz of the San Diego & Imperial Counties Labor Council teamed up to attract the Hilton.

Diane Takvorian of the Environmental Health Coalition similarly was pleased by Cushman’s commitment to improving air quality near the harbor. Providing electrical energy to ships docked at the Cruise Ship Terminal, the Tenth Avenue Terminal, and the National City Terminal enabled the ships’ engines to be turned off, “so they are not spewing that crap into the air,” Cushman explained.

When Black came onto the Port Commission a year after Cushman’s third-term appointment, “I thought ‘oooh, this is going to be a little dicey.’ It wasn’t at all,” Cushman said. “Off we went, yesterday is yesterday and today is today and we worked together and got a lot of stuff done.” For her part, Black said Cushman became her greatest friend and a mentor on the Port Commission, but only after they had a tense, air-clearing discussion. Initially, “we had a very, very difficult relationship. He made me cry in a strategic planning session and I went into his office, and it was a ‘two Jews come to Jesus’ meeting. He sat at his desk and asked, ‘What is your problem?’ and I said ‘I think you are a bully and what you don’t know about me is that I don’t need to be in front of microphones. I’m not running for office – I just really want to make change, and if you’ll just trust me, I’ve been working on these issues for 30 years, way longer than you. I am going to make you look really good. But can we be friends?’ We shook and we’re still friends.”

Cushman had served on more than 70 boards and commissions by the time I interviewed him in December 2021. One was that of Temple Solel, to which he and his family followed Rabbi Lenore Bohm from Congregation Beth Israel. Two that overlapped were the Port Commission and the Convention Center. “Every time we tried to do something at the Convention Center, the naysayers sued us,” Cushman recalled. “I went to Carol Wallace [the Convention Center’s president and CEO] one day and I said, ‘Carol, what can we do? The industry is up in arms. They don’t believe us [when] we say we are going to expand.’ She said, ‘Steve we could enclose the [sail area atop] the convention center.’ ‘What would it cost?’ She said, ’10 million dollars.’” Cushman, then chair of the Convention Center, promptly called David Malcolm, who then was chair of the Port Commission. “I said, ‘David, we need to enclose the sail area; the industry doesn’t believe we are going to do anything. But we don’t have the $10 million. Would the Port loan us the $10 million, interest free, and we will pay you back $1 million a year for ten years?’ He said, ‘Yes, I’ll make that happen.’ So we went into the Port, a closed session, and discussed it, and then went into an open session. The Port agreed to do it, and the interesting thing there was about a year later I end up on the Port. Everyone is giving me a ration, ‘Why the heck did that guy at the Convention Center borrow $10 million and pay no interest, blah, blah.’ The good news is that we paid it off in ten years instead of 20 years. Instead of paying $25 million, we paid $10 million, and I ended up on both sides of the deal. If you look at the plaques in the sail area enclosure, in the back of it, one is to the Port of San Diego saying thank you. My name is on that as a commissioner. The other plaque was to the existing Convention Center Board of Directors which I was on, so my name is on both plaques because I served both on the Convention Center and the Port simultaneously at the end of my Convention Center years. We got that done.”

Making real estate deals for the Port of San Diego was Cushman’s forte. “I led the negotiations on multiple real estate deals with staff because my background is in real estate,” he said. “Kind of like the old police station [near Seaport Village}. There were members of the Port who wanted to just give it away and [Port Commissioner] Duke Valderrama of National City and I felt there was no reason to do that. So, Duke and I made a deal with Terramar [Retail Centers] to give them a finite number of years that they basically had no rent and today that is a market rent project that the Port does very well.”

During his tenure on the Port, Cushman took particular interest in maritime affairs. Prior to his tenure, he said, “Maritime was losing $2 million a year” but the Port had a responsibility under its state charter to further fishing and other ocean-going industries. “So, I became chair of the Maritime Committee and one of the things we did was bring Dole Fresh Fruit Company to San Diego. Dole had been at Port Hueneme forever and ever and ever. Hueneme had some favorable work rules that quite frankly were upsetting to us because we couldn’t get them with our Longshoremen. The chair [of the Port Commission] at the time was Admiral Paul Speer out of Coronado. So, Paul and I jumped on a plane, went up to the Dole headquarters to see David Murdock … He had the biggest office I’ve ever seen in my entire life, and we sat way over on a couch at the end. Mr. Murdock came into his office, and he had huge bay windows looking out on the Port of Hueneme. He said, ‘Gentlemen, if you look out the windows, you will see Port Hueneme and they have been wonderful to the Dole Fresh Fruits Company for many, many years – but, we’re all whores, so if you’ve got a deal, let’s hear it. … Our whole pitch to him was that you get [the equivalent of] a free ship every year, one week of your ship costs nothing — the fuel that you will save just coming into San Diego instead of going all the way to Hueneme. We got it and we still have it to this day.” Dole ships mainly bananas through the Port of San Diego, but occasionally it also ships other fruits and flowers through the Port.

Another source of maritime business came from the wind energy industry. “We are the largest windmill importers in the country with the exception of blades,” Cushman said. “Houston processes more blades through their port than we do. But when it comes to the towers and the nacelles, we are the largest importer of them in the world. They come from Central America and from Korea.”

Cushman was modest enough to say that his judgment was less than full proof as a Port Commissioner. One issue on which he missed the boat, so to speak, was his initial opposition to the berthing of the decommissioned aircraft carrier USS Midway as a museum ship along the Embarcadero. He explained that he and Port Commissioner Jess Van Deventer from National City “were very concerned that it would turn into a big rust bucket that no one would take responsibility for and that it would sit and rot away on our port. Jess and I were really opposed to it.” Later, the two commissioners agreed to support the Midway project if there were a guarantee from its backers of $2.5 million to repair it and or move it, if it turned out to be a big flop. Backers including Vince Benstead and Malin Burnham were among 10 citizens who agreed to underwrite $250,000 each to reassure the Port Commissioners. “So, we knew it would be okay and then we aggressively pushed for the Midway to come to San Diego and that was the turning point. There was tremendous political pressure – (former State Senator) Chris Kehoe was on it – ‘you’ve got to allow this thing.’ It turned out to be most successful. I can’t say I am always right; sometimes I’m wrong.”

Laurie Black

Laurie Black, who served as a commissioner from 2007 to 2009 before resigning to care for her terminally ill husband, urban developer Robert Lawrence, said she found the Port Commission to be very much an “old boys’ network.” In one instance, she heard a fellow commissioner slurring gay people; in other instances, women on the staff and on the commission were denigrated; and during the trial of pyramid schemer Bernie Madoff, who was convicted of bilking his investors of many millions of dollars, one commissioner looked directly at her and said with scorn, “you people!” Recalling the moment, Black commented, “When he looked at me, he saw a Jew; he didn’t see a woman, an American, a Democrat, a mother, a wife, an activist — he saw a Jew.”

Besides the problems of such biases, Black said, the Port Commission suffered from a mindset in which it saw itself as a private business, with a mission to earn money, rather than as a governmental agency, with a mission to serve the people who lived within the member cities.

“It doesn’t always have to be about money, it can be about green space; it can be about parks,” Black told me. Further, she said, the Port needs to do whatever it can to mitigate the impact of industrial areas and shipyards near the predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood of Barrio Logan, where Chicano Park is located. “If children are breathing in those fumes, that is why they get asthma. People are getting sick. The port is government; government is making the people sick.” Fixing the problem should take precedence over subsidizing one hotel developer or another.”

Although her time on the port commission was abbreviated because of the ill health of Robert Lawrence (whose father, M. Larry Lawrence, was the one-time owner of the Hotel del Coronado), Black said she counted some accomplishments of which she was particularly proud. She said that she initiated the idea of allowing the San Diego Symphony to have an outdoor home at the bay. The idea was resisted during her tenure, but eventually it was embraced, so that today the Rady Shell – named for Jewish community philanthropists Ernest and Evelyn Rady — is one of the cultural treasures on the waterfront. Additionally, she said, “I started the Green Port, the environmental committee,” which counts among its accomplishments the Cruise Ship terminal which is certified by LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). Further, she said, she was successful in having the port building on the Broadway Pier set back far enough that people looking down Broadway from downtown could still see the water. She said that Alonzo Horton, who had founded much of downtown in the 19th century, designed Broadway (then known as D Street) for just such a purpose.

“When I had to resign, Steve Cushman was the one who said, ‘Take a leave, it will be okay, take a leave for a few months.’ I said ‘You don’t understand; I have our kids. I’m planning my daughter’s bat mitzvah.’” Laurie and Robert had four children; the youngest was the one with the approaching bat mitzvah.

The Port’s Relationships with Israel

The Port has had some interactions with Israel. Israel’s Zim Lines ships typically call at East Coast ports. However, some products from Israel, including those bound for Imperial County for geothermal facilities built and/or operated by the Israeli company Ormat, arrive in San Diego aboard other cargo ships.

Another Israeli company, ECOncrete, in 2021 replaced existing riprap at Harbor Island with 74 units of interlocking tidepools, each unit measuring a meter and a half cubed and weighing 3.5 tons. The San Diego project “is the first Coastalock pilot in the world,” the company’s president Ido Sella wrote to me via email. Aware that ordinary concrete can chemically react with seawater over time, adversely affecting the ecology, ECOncrete conducted research and development along the shores of the Israeli cities of Herzliya and Jaffa.

Port Commissioner Rafael Castellanos commented that the Board of Port Commissioners is “proud to be partners and to explore together the possibilities of the Coastalock tide pool armor technology. There is an ocean of opportunity out there to grow the Blue Economy, and we are thrilled to join ECOncrete to demonstrate innovative eco-engineering solutions to protect and restore coastal ecosystems.”

Sella and the late Shimrit Perkol-Finkel, who both earned doctorates in zoology from Tel Aviv University, cofounded ECOncrete. Perkol-Finkel was honored as a Marie Curie Fellow by the European Union and had authored 20 scientific papers prior to her death in March 2021 resulting from a truck colliding with the electric scooter she was riding.

The two marine biologists “recognized a man-made hazard to marine life: concrete used to reinforce shorelines and build infrastructure on-shore and off-shore,” Sella said. “Coming from the world of academia, we had the knowledge of what needed to be done to help reduce concrete’s harmful impact on marine ecosystems and, eventually, it got to a point where we both decided to take the plunge and enter the commercial world and make it a reality.

“There are a whole range of environmental benefits to our unique solution, including the fact that the material composition is less harmful to the local ecosystem.” Its “surface structure leads to more biodiversity, better water quality and CO2 sequestration. At the same time, ECOncrete has a 70% lower carbon footprint and our studies have found twice more biodiversity and 7 times more carbon sequestration.”

Once the 60-meter-long project was installed, in two segments of 30 meters, “ECOncrete divers and drone operators monitor the growth of marine biology on the site and the water quality around the site every 6 months, comparing it also to the surrounding infrastructure,” Sella said.

“This is so we can really measure the results and ensure that marine life thrives once again.” Seven months after the installation, “looking at the variety of marine life that has already accumulated around the new infrastructure, even for us this is an amazing success.”

Globally, he said, “with the expected sea level rise top of the agenda, we expect a massive uptick in concrete construction on- and offshore. What drives us is our ability to support any construction company out there that needs to put concrete in the water, with a concrete solution that is actually part of the solution and not creating new problems.”

Jewish-run Businesses Along the Bay

Major Jewish-run businesses along the bay over the years have included Southwest Marine, a shipbuilding concern headed by Art Engel; Seaport Village, a collection of specialty shops and restaurants founded by Ann Taubman; three hotels on Tideland property owned by Richard Bartell (Humphrey’s Half Moon Inn on Shelter Island; Holiday Inn San Diego Bayside near Liberty Station; and the Hilton San Diego Airport on Harbor Island) the Kona Kai Club, owned by brothers Bill Lipin and Bernard Lipinsky; and the Sunroad Marina on Harbor Island owned by Uri Feldman.

Feldman also is in the process of developing a $160 million, 450-room hotel on Harbor Island, expected to begin construction in 2023. Permitting was not an easy process. Besides from the Port Commission, he needed approval from the California Coastal Commission, which insisted that the Port Commission provide access to the coast for people with low incomes. Accordingly, Feldman was given a choice in November 2021: either set aside the equivalent of one fourth of the rooms at no more than $130 a night or pay an offsetting fee of $11.3 million so that 112 affordable rooms can be built somewhere else on Port property, preferably on Harbor Island. In response, Feldman said he would try to find a way to build those rooms himself in preference to paying a fee. One question is where would those 112 units go—would they be on the same 7.5 acre site where Feldman plans to build two buildings, varying in height from 12 to 15 stories, with 198 rooms for extended-stay lodgers and 252 rooms for overnighters? In addition to sleeping accommodations, Feldman’s plan calls for such amenities on the property as conference space, retail outlets, a restaurant and bar, fitness center, jacuzzi spa, and swimming pool, as well as outdoor “destination areas” along a 15-foot-wide promenade.

Feldman also is in the process of developing a $160 million, 450-room hotel on Harbor Island, expected to begin construction in 2023. Permitting was not an easy process. Besides from the Port Commission, he needed approval from the California Coastal Commission, which insisted that the Port Commission provide access to the coast for people with low incomes. Accordingly, Feldman was given a choice in November 2021: either set aside the equivalent of one fourth of the rooms at no more than $130 a night or pay an offsetting fee of $11.3 million so that 112 affordable rooms can be built somewhere else on Port property, preferably on Harbor Island. In response, Feldman said he would try to find a way to build those rooms himself in preference to paying a fee. One question is where would those 112 units go—would they be on the same 7.5 acre site where Feldman plans to build two buildings, varying in height from 12 to 15 stories, with 198 rooms for extended-stay lodgers and 252 rooms for overnighters? In addition to sleeping accommodations, Feldman’s plan calls for such amenities on the property as conference space, retail outlets, a restaurant and bar, fitness center, jacuzzi spa, and swimming pool, as well as outdoor “destination areas” along a 15-foot-wide promenade.

*

Next Sunday, July 17, 2022: Exit 18A (Pacific Highway): Old Town Trolley Tours

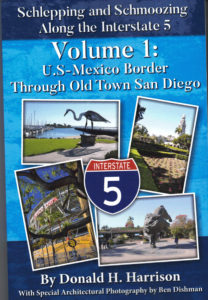

This story is copyrighted (c) 2022 by Donald H. Harrison, editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. It is an updated serialization of his book Schlepping and Schmoozing Along Interstate 5, Volume 1, available on Amazon. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com