Chapter 30, Exit 18B (Washington Street): San Diego County Sheriff’s Museum

From Washington Street exit turn right to San Diego Avenue, turn left to Sheriff’s Museum at 2384 San Diego Avenue. It will be on your right.

From Washington Street exit turn right to San Diego Avenue, turn left to Sheriff’s Museum at 2384 San Diego Avenue. It will be on your right.

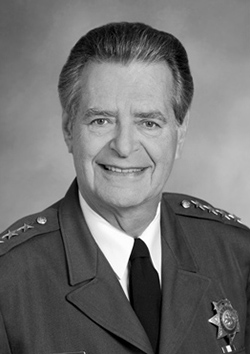

The San Diego Sheriff’s Museum to a large degree, reflects the visions of John Duffy and his successor as sheriff, William “Bill” Kolender. Kolender was a former San Diego police chief who later was elected four times as the county sheriff, serving from 1995 through his retirement in 2009. Kolender died in 2015 with Alzheimer’s Disease.

The museum began informally in 1981 when retired Deputy Sheriff Don Van Hooser began collecting historical memorabilia under Kolender’s long-time predecessor Sheriff John Duffy. For a while the artifacts of the museum were housed at the Sheriff’s Communication Center, and later they were moved to the Santee substation. In the year 2000, under Kolender, it moved into the present site, where the collection could be easily accessed by the public.

The museum is located “right on top of the site where our first Sheriff, Agoston Harazsthy’s, original cobblestone jail once stood,” according to the museum website. “A few highlights of the museum include a behind-the-scenes look at crime fighting and an 1850’s cobblestone Sheriff’s Office complete with an original jail cell that can be compared to the modern day in the next room. Visitors can listen to live radio calls, see a real Sheriff’s motorcycle, a helicopter and bomb detection robot, and a patrol car from the Duffy era. A weapons gallery features an exciting display of over 200 confiscated weapons. Other galleries include California history, courtroom, drugs and gangs, and a special gallery that honors the special deputies who were killed in the line of duty. Visitors can purchase souvenirs and gifts from the museum’s gift shop. The courtyard can be used for special events and has been used to host several law enforcement conferences.”

A member of the Jewish community, known for his self-deprecating sense of humor, Kolender grew up at the Reform Congregation Beth Israel. However, when it was time for his bar mitzvah, he honored his grandfather’s wishes and had it at Beth Jacob Congregation, which is Orthodox. “The rabbi there was Baruch Stern, and it was the first bar mitzvah for him after the war,” Kolender told me back in 1996 when I profiled him for the now defunct San Diego Jewish Press-Heritage. Rabbi Stern’s children “had been killed in front of him by the Nazis, and he started crying and I started crying, and I’m not sure if we ever did get through the whole thing. It was something I never will forget.”

Kolender joined the San Diego Police Force as a rookie in 1956 and then held every rank until 1975 when, at the age of 40, he was selected by then-Mayor Pete Wilson to serve as the police chief. Famous for his ability to have a convivial conversation with almost everyone, Kolender faced a real challenge while working as a community relations officer during the turbulent 1960s. He was sent into an African-American neighborhood to meet with some Black militants. As the story is told, Kolender listened complacently as his youthful interlocutors heaped one epithet after another upon the police, but he put up his hand in mock warning when they used the slang term “pigs” to describe Kolender and his fellow officers. “I don’t mind those other names,” he reportedly said. “But ‘pig’? What kind of name is that to call a nice Jewish boy?” At first, Kolender’s comment provoked nothing but blank stares. Then someone who had heard that Jews don’t eat ham or pork started to laugh and others joined in. “That’s when we all began to talk,” Kolender recalled.

There may have been times when his self-deprecating humor may have made some of us in the Jewish community wince in fear that in trying to break down stereotypes, he occasionally ran the risk of reinforcing him. He once told a “bad news, good news” type joke when someone asked him what it was like being the city’s first Jewish police chief. “Well,” he replied, “crime unfortunately has gone up, but this is the first time the department has ever made a profit.”

After 13 years as San Diego’s top cop, Kolender took a job as an assistant to publisher Helen Copley of the Union-Tribune Publishing Company. When Pete Wilson, who had gone on to serve a term as a U.S. senator, later was elected as California’s governor, Kolender followed him to Sacramento to serve as director of the California Youth Authority. He subsequently won his first term as sheriff.

As sheriff, Kolender paid attention to the way his 1,800 deputy sheriffs and 1,200 non-uniformed personnel interacted with people of other faiths, races, and sexuality. He stated that “the way we react inside is the way we will react outside.” In his department, he said, “racism and sexism are not tolerated. It is the responsibility of the leadership to let people know that. Most people will do what they think their boss wants them to do and what will make them successful. Wherever I have worked, racism and sexism are sure formulas for failure and most people don’t want to fail. So, you approach it from that end as well as the human end by educating them.”

He also preached personal accountability. “Kids get busted, you hold them accountable,” he once told me. “My oldest boy got arrested when he was just 18 for drunk driving. He called me at 1:30 in the morning and it was the hardest thing I ever did. I said ‘Michael, you did the drinking; you do the paying.’ He stayed (in jail) overnight, and the next afternoon, late, I went and picked him up, and, as we were walking out, he started bad-mouthing the cops, cussing them, saying he only had 13 beers, and I knocked him right on his ass. He handled the case himself, got it reduced to reckless driving…. {Twenty-two years later] he kisses me for that day he spent in jail. That brought us together, not apart. It shows that kids want to be held accountable.”

Both as a police chief and as sheriff, Kolender was an advocate of a program he called COPPS for Community-Oriented Policing and Problem Solving. Noting that the concept was often misunderstood by the police officers on the beat as meaning “social work,” Kolender explained “the idea is to improve the quality of life and solve problems as they affect law enforcement. The only way it is going to work is the officers understanding how to form collaborative efforts and involve people in helping them to solve the problems. The public can’t do it alone, the police can’t do it alone, but with the help of other agencies we can in fact do something.”

Both as a police chief and as sheriff, Kolender was an advocate of a program he called COPPS for Community-Oriented Policing and Problem Solving. Noting that the concept was often misunderstood by the police officers on the beat as meaning “social work,” Kolender explained “the idea is to improve the quality of life and solve problems as they affect law enforcement. The only way it is going to work is the officers understanding how to form collaborative efforts and involve people in helping them to solve the problems. The public can’t do it alone, the police can’t do it alone, but with the help of other agencies we can in fact do something.”

He posed as an example a neighborhood suffering from armed robberies. “How do you solve that? What do you do, aside from arresting the people who are committing them? How do you keep them from occurring? You can sit down and evaluate the places that are being robbed. What is the commonality? What can you do? Lights, cameras, training of the clerks address one component. Where there are gangs, he added, officers can participate in efforts to create educational and recreational alternatives.”

*

This is the final copyrighted story from Volume I of “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” Along with Volume II, the book is available in its entirety on Amazon. Soon to be published will be Volume III, completing the journey, with a Jewish story at every exit, from San Diego County’s border with Mexico to the Orange County line.

Good article on Bill Kolender ! What is your email address ?

Len Krouner

I may be reached via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com