By Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin

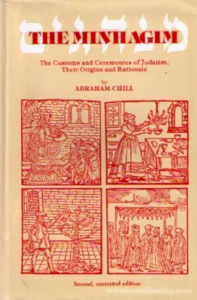

BOCA RATON, Florida — Judaism has dozens of meaningful customs and ceremonies, but most people, even Jews, do not know all of them, their origins and their rationale. Rabbi Abraham Chill (1912-2004) gives readers of his book The Minhagim, Hebrew for customs and ceremonies, a very readable discussion of many Jewish practices.

The following are some, but not all, the questions that Rabbi Chill addresses regarding Sukkot. Leviticus 23:33-44; Deuteronomy 16:13-17 calls Sukkot the “Festival of Tabernacles” and “Feast of the Ingathering of the Fruits.” He raises the questions to make us think. I do not include Rabbi Chill’s answers.

Sukkot begins on the 15th day of the Hebrew month Tishrei, five days after Yom Kippur, which occurs in the fall, and continues for seven days in Israel and eight days outside Israel. The seven days in Israel are immediately followed by another holiday called Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, two holidays with different purposes occurring on the same day. A day is added outside of Israel, the eighth day is Sukkot, and the ninth added day is called Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah.

Sukkot begins on the 15th day of the Hebrew month Tishrei, five days after Yom Kippur, which occurs in the fall, and continues for seven days in Israel and eight days outside Israel. The seven days in Israel are immediately followed by another holiday called Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, two holidays with different purposes occurring on the same day. A day is added outside of Israel, the eighth day is Sukkot, and the ninth added day is called Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah.

Questions to make us think

What do Sukkot and dwelling in sukkahs teach Jews? Why sit in the Sukkah in the fall and not spring when the weather is more comfortable?

Since one purpose of Sukkot is to remind Jews of the exodus from Egyptian slavery, why doesn’t it coincide with Passover when the exodus occurred?

What does Shemini Atzeret teach? Why is it added to Sukkot and not another holiday?

Whereas Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret are biblical holidays, Simchat Torah (meaning, Joy over the Torah) is post-biblical and began in the Common Era. Why was it invented? Why have it joined to another holiday? (I would add, why isn’t Simchat Torah connected to Shavuot, the holiday that recalls the giving of the Torah?)

The day before the last day in Israel and before the last two days outside Israel is called Hoshana Raba. The day is not mentioned in the Torah. Why was it instituted? What is its purpose? In synagogues, Jews walk around the bima, the podium from where the cantor leads the service, holding the lulav and etrog seven times. Later, one beats the aravot (willows) five times. Why walk seven times and beat five times? What do the acts teach?

Why on Simchat Torah do Jews circle the bima with Torahs seven times? Why are children called up to the reading of the Torah on this day but no other day? What is the purpose of giving one man the honor of Hatan Torah and another man Hatan Bereshit? The first means “Bridegroom of the Torah,” and his honor is to read the end of the Torah. The second is “Bridegroom of Bereshit,” the beginning of the annual reading of the Five Books of Moses. What is the significance of “bridegroom?” Why begin reading the Torah after Sukkot and not Simchat Torah?

What are we taught by using the four species over which a blessing is made, the lulav, etrog, hadas (myrtle), and aravah (willow)? Why does the blessing only mention the Lulav? Why are the four species waved after saying a prayer (we do not waive the Shabbat candles or the challahs or wine and other items for which we make a blessing)?

Why did the rabbis require the three species to be tied together, but not the etrog?

Is the notion of the visit of seven long-dead ushpizin (guests visiting the Sukkah, such as Abraham and King David) a superstition? Why was it instituted? (I would add, why is the number seven repeated so often in the practices of these holidays?)

Why did the ancient rabbis say that the pouring of water on the Temple altar, a ceremony called Simchat Bet ha-Sho’evah, was the most joyous occasion in the Temple on Sukkot? Why did the Sadducees oppose it? Why was it done? Why water, when usually wine is poured on sacrifices on the altar?

These questions prompt answers that help us understand Judaism better. Rabbi Chill gives answers in his easy-to-read book.

*

Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin is a retired brigadier general in the U.S. Army chaplain corps and the author of more than 50 books.