By Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin

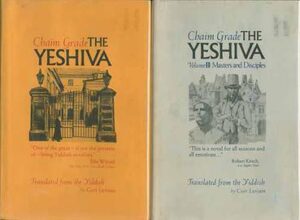

BOCA RATON, Florida — I wrote in past reviews of Chaim Grade’s books that I and many others are convinced Grade deserves the Nobel Prize for literature. Most readers of his book published in Yiddish in 1967, titled Tsemakh Atlas and translated into English in 1976 as The Yeshiva in two parts, will agree. The first part, reviewed here, is 387 pages, and the second is 394. Many consider The Yeshiva his crowning achievement.

Regarding Musar, he rejects the generally accepted view that people should act according to the Golden Mean, in moderation, between extremes. An example of the Golden Mean is courage. A proper courageous hero is not cowardly, fearful, hiding away from danger, or fearlessly rushing into unsafe situations without care. He assesses the difficulty, plans how to overcome it, and faces and overcomes it. Tsemakh rejects caution. He insists that people should behave most strictly, even if it provokes anger, which it usually does. Grade knew this extreme view of Musar since he, born in 1910, attended a Musar Yeshiva as a student until he was 22 in 1932, when he left the rabbinic world and Orthodox Judaism and began his writing career as a poet and later as a novelist. But, unlike Chaim Atlas, Tsemakh Atlas did not abandon Orthodoxy as he understood it. Although, despite his insistence on stringency, Tsemakh is flawed, inconsistent, and attracted by female beauty.

I have seen no explanation of Tsemakh Atlas’ name. The Hebrew word tsemakh means “growth.” The word atlas is used in English and Hebrew to indicate a map or chart, but also one who bears a heavy burden, as the Titan in Greek mythology whom the Greek god forced as punishment for betraying him to carry the heavens on his shoulders. It is possible that Chaim Grade gave him this name because the rabbi attempted to improve and grow to control his emotions and carry his heavy emotional burdens.

Besides the overall story and his outstanding writing, what stands out for me is his treatment of the many people in the novel. I read a lot. But I cannot remember any writer who tells us so much about every character in the book. When a person is introduced, whether male or female, young or old, Jewish or non-Jewish, even if the person appears for a very short time, interesting information is given about that person, which is so detailed that it is like a story in brief.

The translators of book one devote three pages to “Cast of Characters,” telling us their names, when they appear in the six cities where Tsemakh travels, and a few words about them. This listing shows us how many people populate this novel, people whose character is told in brief tales. There is one in Navaredok, Tsemakh’s teacher; two in Nareva, Tsemakh himself and the head of the Musar yeshiva; three in Amdur, Tsemakh’s fiancée, her father, and an innkeeper; 19 in Lomzhe, including members of Tsemakh’s family and people associated with the yeshiva; 16 in Vilna, town people and a brilliant young man, Chaikl, who becomes Tsemakh’s pupil; 26 in Valkenik, including students of Tsemakh and a renowned scholar, rabbi, and sage who saves Chaikl from Tsemakh. It is significant that despite the vast number of people in the drama, 68 people, readers do not confuse them with other people because of Chaim Grade’s skill. It is like a loving father selecting dissimilar strands of colored silk and weaving them into a single coat of many colors as a gift to a cherished child.