By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Imagine that you built a bridge out of Jengo blocks, and you wanted to see who could more accurately and more quickly replicate your bridge. Would it be students between the ages of 7 and 13 who watched a 20-second video of you building the bridge, step by step? Or would it be students of the same age range who simply viewed the bridge for 20 seconds and then, after it was removed from view, started building a copy from memory?

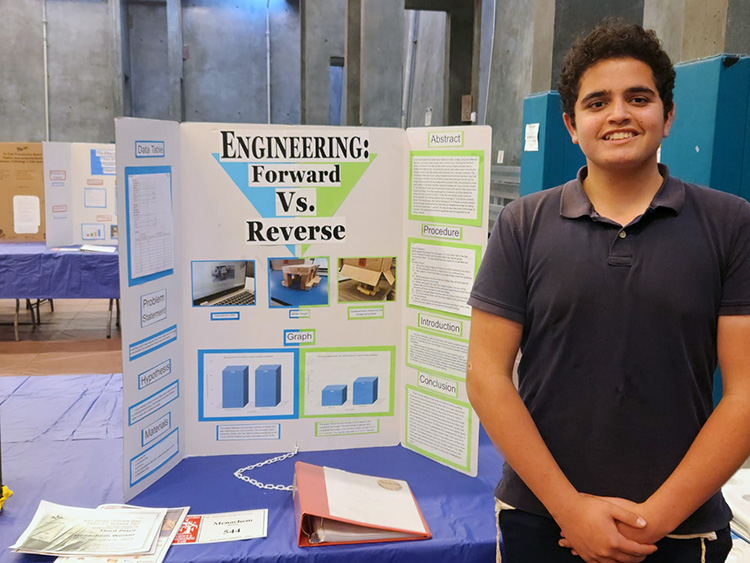

Menachem Weiser, a 14-year-old student at Soille San Diego Hebrew Day School who designed the experiment, assumed that the students who watched the video would do better. He divided students at the Orthodox day school into two groups, trying his best to equalize the age range and genders of the two groups.

The group that tried to build the bridge after watching the 20-second video were engaged in a process known as “forward engineering.” Those who looked at the bridge, memorizing what they could in 20 seconds, were engaged in “reverse engineering.”

As it turned out, Menachem’s initial hypothesis was mistaken. The “reverse engineering” students outperformed the “forward engineering” students on the more important of two variables – being able to finish building a bridge in less time than the allotted one minute.

Of the 29 reverse engineers, 11 percent finished the exercise in less than one minute, whereas of the 36 forward engineers, only 8 percent were able to do so.

The other variable—the average number of blocks placed in the correct positions—was close to a tie. The forward engineers had an average of 13.33 blocks compared to 13.28 for the reverse engineers.

Menachem’s experiment won a first-place award in the junior division of the 69th Annual Greater San Diego Science & Engineering Fair that was judged March 15 in Balboa Park. Along with his award, Menachem won an invitation to enter that project into the 72nd Annual California Science & Engineering Fair, which because of staffing shortages will be entirely virtual on April 11.

The state science and engineering fair reports that 900 sixth through twelfth graders from 400 schools throughout the state will present 800 projects for judging.

Menachem has a hypothesis why his initial prediction was wrong about forward engineering outperforming reverse engineering.

He said that forward engineers watching the video had to watch the process step by step, in some cases spending an inordinate amount of time focusing on steps that were already obvious to them. On the other hand, reverse engineers could give more attention to the part of the bridge-building process that was more complex.

To be more specific, most people know instinctively how to build the pillars upon which the span of the bridge rests. But the top, or span, of the bridge requires more thought. Reverse engineers in essence had more time to conceptualize the span of the bridge before starting construction.

Rabbi Simcha Weiser, who is the headmaster at the Hebrew Day School, is Menachem’s grandfather. Menachem’s father, Yisroel, is a teacher at the school.

Menachem told me that he is very good at origami – making “crazy things” out of paper – and also considers himself a “decent magician.” He said he has designed his own magic tricks.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com