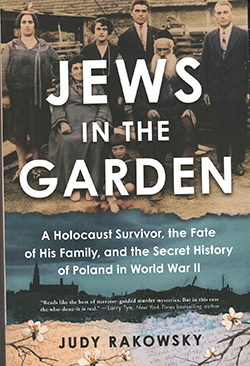

Jews in the Garden: A Holocaust Survivor, the Fate of His Family, and the Secret History of Poland in World War II by Judy Rakowsky; Source Books; © 2023; ISBN 9781728-254623; 335 pages plus acknowledgments, reading group guide, a conversation with the author, bibliography and notes; $17.99 on Amazon.

SAN DIEGO – Author Judy Rakowsky, who covered crime for such news outlets as the Boston Globe, the Providence Journal, and People magazine, turned her investigative talents onto the fate that some members of her extended family suffered during the Holocaust. The memoir is both a deep dive into the guarded, selective memory of non-Jewish Poles and an illustration of the way fine journalists doggedly pursue a story.

SAN DIEGO – Author Judy Rakowsky, who covered crime for such news outlets as the Boston Globe, the Providence Journal, and People magazine, turned her investigative talents onto the fate that some members of her extended family suffered during the Holocaust. The memoir is both a deep dive into the guarded, selective memory of non-Jewish Poles and an illustration of the way fine journalists doggedly pursue a story.

Five members of the Rożeńek family were pulled from their hiding places in 1944 by armed members of a militia, forced to jump from a second-story window, and riddled with bullets on their way down. One member of the family, who was hiding in an outbuilding, observed the massacre and escaped into obscurity.

The shocking fact was that the killers were not Nazi Germans; they were Poles, who later would be described as Partisan resisters against the Nazis. Whether they were enemies or not with their country’s occupiers, they shared with them one characteristic: virulent antisemitism.

The Polish family that had hidden the Rożeńek family for 18 months barely escaped with their lives, but their children and grandchildren thereafter lived under a cloud. The German Nazis had threatened retaliation against the entire population of any village where Jews were found to have been assisted in hiding. Rakowsky found that as far as many Polish townspeople were concerned, even decades after the massacre, the rescuers, not the murderers, were more at fault. In the cold calculus of World War II, whereas the rescuers had put the town in danger, the murderers had removed the threat.

The five murdered members of the Rożeńek family were buried in the garden of their rescuers’ home, and the only survivor, the terrified, 16-year-old Hena disappeared.

Sam Rakowsky was the second cousin of author Judy Rakowsky, although he was considerably older. Whereas Judy’s family had immigrated to the United States from Poland prior to World War I, Sam’s family had remained in Poland. He was a Holocaust survivor.

Sam made it his mission to return to Poland again and again, to renew pre-World War II acquaintances and to try to track down his cousin Hela, who had dropped out of sight. Having interviewed and written about Sam for newspapers, Judy decided to cover his return to Poland and his search for the missing Hela. They visited Poland again and again over several decades in an attempt to wrest information from former neighbors, friends, and customers of Sam’s father’s lumber yard. Again and again, most of their Polish informants told them that they had no idea what had happened to Hela. Yet, there was always something unconvincing about their denials.

Crime reporter that Judy was, she suspected a cover-up. Even though Sam’s old neighbors treated him with superficial friendliness, Judy sensed that long-ingrained hatred of Jews lurked beneath the surface.

Along the way, Rakowsky discovered that this murder by Polish “bandits” of Jews who had been in hiding was not an isolated incident. In fact, another branch of her family suffered the same fate in another town. And so had hidden Jewish families throughout Poland. But digging out the story became increasingly difficult as a new government tried to make it a criminal offense to disparage the role of Poles in connection with the Holocaust.

I could relate personally to this remarkable, well-told tale. I had sensed the same distrust of me, as a Jewish reporter, inquiring about a former Jewish resident of a small town in what is today Slovakia, whose early life I had hoped to chronicle for this publication.

My inquiries were about Judge Jacob Weinberger, who had left Slovakia in the 19th century as a youth, achieving success in this country as a delegate to the 1910 Arizona statehood convention, and later as an attorney and federal judge in San Diego County. One of our city’s courthouses is named for him. Whenever I wrote, or telephoned, the municipal authorities in his hometown to seek information about the town as it may have appeared during Weinberger’s lifetime, I was either ignored or brusquely put off.

Weinberger had left Slovakia on his own accord well before the Holocaust, but the family’s obvious Jewish name raised defenses similar to those encountered by Sam and Judy Rakowsky in Poland. A non-Jewish acquaintance of Slovakian origin who offered to help ran into the same kind of nasty resistance.

When Nazis forced Jews to leave their homes and businesses, many non-Jews either took these businesses and homes over or looted them. The ill-begotten goods often were sold at discount to others. In one memorable incident in Rakowsky’s book, she and Sam were shown the dining room table that had once belonged to Sam’s family. The Polish family who owned it bragged about the good price they had paid for it. And, chutzpah!, they warned the Rakowsky’s against attempting to repossess it, which Sam, who had made a financial success in America, had not the slightest interest in doing.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com