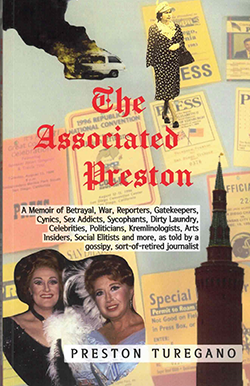

The Associated Preston by Preston Turegano; San Diego State University Press (c) 2022; ISBN 9781938-537219; 272 pages; $26.95 on Amazon.

SAN DIEGO — An employee of the San Diego Union-Tribune and its predecessor Evening Tribune for 36 years until his retirement in 2006, author Preston Turegano had been an editorial assistant, general assignment reporter, and arts critic. He once was told by an editorial supervisor that people in the arts community were afraid of him. A colleague reassured him, “People don’t hate you because you’re gay; people hate you because you are you.”

SAN DIEGO — An employee of the San Diego Union-Tribune and its predecessor Evening Tribune for 36 years until his retirement in 2006, author Preston Turegano had been an editorial assistant, general assignment reporter, and arts critic. He once was told by an editorial supervisor that people in the arts community were afraid of him. A colleague reassured him, “People don’t hate you because you’re gay; people hate you because you are you.”

Folks in the arts community weren’t the only ones who worried about what Turegano might say about them. His colleagues in the newsroom, even those who are long retired, worry about what Turegano, whose Tribune desk was considered gossip central, might write or say about them. Happily accepting the title of office “yenta,” Turegano rarely could be constrained in his criticisms — either in his columns or in the notes he would post about people on a U-T bulletin board.

Turegano writes he didn’t mind being labeled a yenta by Lee Grant, who for a time was Arts editor at the U-T and was “himself Jewish” because “I am a descendant of Sephardic Jews–Spanish Jews. I learned this in 2004 from a distant relative in Louisiana who said one of his grandmothers was a Turegano.” The cousin had extensively researched the family tree, and reported the Turegano surname was particularly prominent in the rolls of a 12th century synagogue in Toledo.

Turegano’s admiration for Jewish words and culture are apparent in the title he gave Chapter 36 in his memoir, “Menschen and Shmucks” in which he assigns some of his former supervisors and colleagues to each category. In another chapter. he revealed some of the newsroom nicknames given to his colleagues. One was “Golem Girl” for a reporter who “like the mythical stone golem in Jewish folklore spread fear when it walked. G.G. was known to go to the offices of high-up U-T executives to complain about things she didn’t like in the newsroom or to ask for special assignment/ beat consideration.”

Through his career, he received criticism as well as dishing it out. In 1989, Turegano, an opera lover, reported that in the final act of La Boheme, the San Diego Opera had an actress in a flesh-colored body stocking serve as a model for the artist Marcello, rather than an actually nude model. Ian Campbell, the Jewish general manager of the opera, wrote indignantly that was not true. The model was indeed nude. Turegano shrugged, “Well how would I know? My last contact with a vagina occurred the day I was born.”

Besides Campbell, some other members of the Jewish community who rated a mention in the memoir — some favorable, some otherwise — included the previously mentioned journalist Lee Grant, and U-T colleagues Suzanne Choney, Jay Levin, Rick Levinson, Robin Maydeck, and Ken Stone. Additionally, there were journalists with other organizations such as anchor Marty Levine with KNSD, Larry Remer with San Diego Newsline; and former KNSD president Phyllis Schwartz, who took umbrage at a “swipe” Turegano took in his column at a female anchor.

Remer, whose daughter Terra Lawson-Remer is now an elected member of the San Diego County Board of Supervisors, was inadvertently involved in an incident that prompted Turegano to be suspended from the U-T for three days. Turegano confirmed for Remer, who wrote a “tidbit” column that whereas a morning San Diego Union reporter was denied an opportunity to take a freebie trip, her counterpart on the Evening Tribune was allowed to accept a similar junket. The point of the item was that the two papers, although owned by the same publisher, apparently operated under different standards.

A more serious breach with the paper came when Turegano was sitting with a friend in Balboa Park and was approached and flirted with by other men who turned out to be members of the San Diego Police vice squad. The officers arrested Turegano and his friend on charges of soliciting sex, a charge that prompted his employer to fire Turegano. But the charge, stemming from an obvious case of entrapment, was thrown out, and Turegano won his job back. From that point on, he publicly celebrated his gay identity to the discomfort of some closeted gay colleagues on the Copley newspapers.

Jewish public figures whom Turegano mentioned in his memoir included former San Diego Mayor Susan Golding and her former husband Richard Silberman, who was convicted of money laundering; Bill Kolender, who worked for the Union-Tribune publishing company between stints as San Diego’s police chief and San Diego County’s sheriff; San Diego Symphony’s one-time board chairman Herb Solomon and one-time conductor Yoav Talmi, and the symphony’s ongoing benefactors Irwin and Joan Jacobs. Another was M. Larry Lawrence, the one-time owner of the Hotel del Coronado and U.S. Ambassador to Switzerland, who was disinterred from Arlington National Cemetery after it was reported that he had not served in the U.S. Merchant Marine as it was claimed. “This gave new meaning to ‘digging up dirt on someone,'” the U-T’s one-time gossiper in chief note approvingly.

Jewish celebrities Turegano met or interviewed included opera diva Beverly Sills, and at the home of U-T publisher David Copley, the sister advice columnists, Eppie Lederer (Ann Landers), and Pauline Phillips (Dear Abby).

When the Tribune and Union were merged, Turegano was told by a supervisor, “You’ve written things posted on our office bulletin board that have hurt people and made some people cry. That will stop!” Fat chance.

What kept Turegano working at the U-T for more than three and a half decades was his excellent reporting. He won a first-place award from the San Diego Press Club for his coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Southern California in 1983. As an investigative reporter, he exposed how heads of two well-known non-profit arts organizations turned in bloated expense accounts.

I have covered Jewish news in this community since the mid 1980s yet learned something affecting our community in this memoir that I had never heard before. As part of the team covering the Sept. 25, 1978, midair collision between a PSA commercial jet and a small passenger plane that killed 142 people, Turegano was sent by the Tribune to the temporary morgue that was set up at St. Augustine High School. He wrote that “for hours, the bags arrived and were partially opened on the wooden gym floor so priests, armed with holy water, could bless the remains. I wondered: Even victims who possibly were Jewish? How presumptuous to think all the dead were Christians.”

Turegano has a network of friends and also plenty of justified critics who reacted angrily to his unfettered opinions about them. I believe that controversial though he may be, this memoir deserves a place in the canon of historical books about San Diego. It vividly describes, some say unfairly, the workings of the city’s largest newspaper outlet at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com