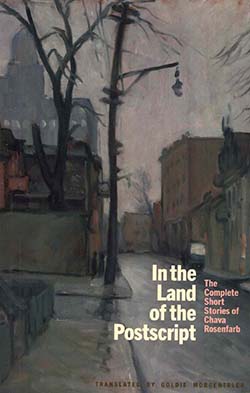

In the Land of the Postscript: The Complete Short Stories of Chava Rosenfarb translated by Goldie Morgentaler; Amherst, Massachusetts: White Goat Press, the Yiddish Book Center’s imprint © 2023, ISBN 9798987-707845, 296 pages plus bibliography; $18.95.

SAN DIEGO – This year, 2023, was declared in Lodz, Poland, to be the year of Chava Rosenfarb, one of its most famous Yiddish writers. In Lethbridge, Canada, meanwhile Goldie Morgentaler, daughter and translator of Rosenfarb from Yiddish to English, completed for publication 10 of her late mother’s stories.

SAN DIEGO – This year, 2023, was declared in Lodz, Poland, to be the year of Chava Rosenfarb, one of its most famous Yiddish writers. In Lethbridge, Canada, meanwhile Goldie Morgentaler, daughter and translator of Rosenfarb from Yiddish to English, completed for publication 10 of her late mother’s stories.

The volume’s title, In the Land of the Postscript, is apt. Whereas all the stories concerned Holocaust survivors who had immigrated to Canada, every one of the characters had lived the main body of their lives, the most unforgettable chapters, during the Holocaust. No matter where they went – be it to new homes in Canada, or on getaway trips to South America, Africa, or France – their memories of the horror kept pursuing them, often propelling their choices, their actions, and their fates.

“The Greenhorn” deals with an immigrant who sees in his new boss in a textile sweatshop a Kapo who made his life miserable in a concentration camp. “Last Love,” about two refugees from failed marriages in Canada who meet and fall in love in Paris, finds Amalia telling the lover who became her second husband, “Do you know, Gabriel, what the most powerful forces were that shaped my life? They were love and fear of death. And they both expressed themselves in erotic passion, in my sexual excitement. It is true that the climax of pleasure and death are related.”

In “A Friday in the Life of Sarah Zonabend,” we learn why she always feared that day. The reasons included the fact that “Her mother had died in the camp on a Friday … One late Friday afternoon, after a selection in the camp…those women whose lives had been spared returned to their barrack and climbed up onto their bunks in the dark. It was then that Crazy Bluma had exclaimed, ‘Children have you forgotten? Today is Friday, Sabbath eve! Quick! Let’s light the candles and bless them!’ And in the dark Bluma went through the motions of lighting the Sabbath candles, while all the other half-mad women in the barrack—those whose lives had so recently been spared—covered their faces with their hands and mumbled the blessing of the lights, whether they knew the words or not.”

“Edgia’s Revenge” told of a woman whose life had been protected in a concentration camp by an otherwise brutal Kapo. The two women met in Canada after the war, Edgia keeping to her promise not to ever identify Rella as a Jewish prison guard. At first Edgia was submissive to her former guard, later she became aggressive toward her. Pavel, who was close to them both but unaware of their previous relationship in the camp, analyzed Edgia accurately when he observed, “Once she was servile, now she is aggressive, and it all springs from the same source, from her feelings of worthlessness… (I)t seems that not even love can repair the wounds she suffered in the camps. Maybe if she could just bring it all out from inside her.”

“Little Red Bird” tells of a survivor so haunted by the loss of her daughter, Feigele, that she kidnaps another little girl from a hospital. She and her husband take the infant to the Yucatan peninsula to raise as their own.

“Francois” is a story of imagination running wild. On a trip to South America with her rude, verbally-abusive husband, Leah conjures a handsome, suave, male friend, who idolizes her, as another companion. But her reverie is shattered in Pucallpa, Peru, at an inn run by a German-speaking family, whom she fears are ex-Nazis escaped like so many others to Latin America. The innkeeper’s wife “seemed to Leah to resemble an SS woman … who had flexed her muscles at a concentration camp somewhere in Poland and Germany. Leah discouraged her advances saying in English, ‘I do not speak German.'”

“Serengeti” is another story in which the principals are stalked by the Holocaust. A professor who had changed his surname from Brownstein to Brown learns that a junior member of his psychiatric department had been a hidden Jewish child during the Holocaust after she was thrown from a concentration camp-bound train by her mother, leaving an indelible scar on her forehead and a sense of shame over being Jewish. The professor feels “a stirring in his heart. He too considered his Jewishness a sign of shame, a cause for guilt, a scar on his soul. The veil he had drawn over his consciousness was related to this shame. Because he felt the crippling burden of his Jewish fate, he never saw himself as a complete person.”

“The Masterpiece” is a tale of long-hidden infidelity. Within it, we find the protagonist, a writer on Holocaust subjects, accusing himself of just playing at his craft. “Having described people starving from hunger, he had sat down to a feast at his dinner table. Having described a character’s terrifying loneliness, he had gone to bed with his wife. Having described executions by firing squad, he plunged into the lake to frolic with his children…”

“Letters to God” tells of a son who survived the concentration camps while also helping his father to do the same. Now his father is comatose on his death bed. “I see the two of us in the camp, and I recall how our roles changed,” he says at his father’s bedside, although it is not at all certain that he can be heard. “I began to act the father to you and in the process became your consoler and your consolation. In the camp it was impossible to argue with a treasure so miraculously saved as one’s own flesh-and-blood father. We clung to each other. We nursed each other’s wounds. We shared every crumb of food.” However, the relationship had taken a turn very much for the worse since then.

The final story, “April 19th,” the date on which the Warsaw Ghetto uprising commenced, deals with a man’s inability to move on from the memory of his lost wife, Rivkele, even though since then he and Bronia had married and had two children. ‘In time the two women merged in Hersh’s imagination, despite the fact that they did not resemble each other physically and despite the fact that their voices were not similar and their laughter was not alike. But he continued deluding himself that in all essentials they were the same, never remembering the differences between them.”

Yes, they are all Survivors, but their stories are not the same, far from it. The experiences of the Holocaust played on their minds in different ways. Rosenfarb, a keen observer of everything she saw – whether it be weather, scenery, customs, or people – was able to penetrate the psyches of her well-drawn characters, enriching our understanding of the now ebbing lives of Holocaust survivors. Goldie Morgentaler understood her mother’s nuanced writing very well, providing us with an English-language volume that can well be savored.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com