By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — Until my twenties, I was a Jew in the USSR, but I was not an Israeli. The Six-Day War changed the consciousness of many, including mine: it was possible to become like all other nations – to be a normal person, one of the people, of one’s own people.

Gradually, I began to study the history of the Jews and the Zionist movement, and taught Hebrew underground. There was a historian of the Jewish people, Heinrich Gretz, who lived in Germany in the eleventh century. He spoke of the medieval Spanish poet Yehuda Halevi (1075-1141): [His] “burning longing for the Holy Land – the birthplace of vision and prophecy, the cradle of Jewry – turned the country where he was born into a foreign land for him.”

Something similar happened to me: I was tired of living as a guest. Spiritually, I had lived in Israel long before I came here. The Voice of Israel radio station was my imaginary address, the only thread that connected me to the country physically. “Voice of Israel” was heavily jammed with powerful Soviet jammers by an unpublished decision of the authorities. As I sat at the radio, listening intently to the voice of the country of the Jews, I could not imagine that years later I would give several dozen interviews to this radio station.

On October 21, 1979, I left Kiev, the city of my childhood and youth. I was labeled a traitor to the homeland and an enemy of the people. Five days later I arrived in Israel. Thus, began my journey to a country of limited opportunities and unlimited dangers, to a country with uncertain borders and certain enemies, to a country of three seas and three deserts, standing at the crossroads of three continents, to a country flowing with milk, honey and blood.

The director of the Institute of Physics, where I worked in Kiev, summoned me for a conversation about my desire to leave for permanent residence in Israel and informed me that I was a traitor to the motherland. As deputy editor-in-chief of the Ukrainian Physics Journal, he decided to withdraw my article from the forthcoming issue of the journal – “articles by traitors to the motherland cannot be published in national journals.”

Thirty years earlier, a set of my father’s book on the Danish writer Martin Andersen Nexø was destroyed because he, a professor at Kiev University and editor of the main Ukrainian journal Homeland, and other Jewish intellectuals were accused of “homeless cosmopolitanism,” a betrayal of socialism and the Soviet homeland.

My father’s favorite poet was the German poet, a Jew, Heinrich Heine, whose work my father researched, wrote laudatory articles about, and because of his love for him he was repressed in a “socialist country” where Heine was considered a “petty-bourgeois poet.”

Like my father, I was presented as a traitor to the homeland and an enemy of the USSR. Although my immigration to Israel was legal, I was honored with the title of “traitor to the homeland.” My father was labeled a “traitor to the homeland” in 1949, although he loved the USSR and socialism. I was labeled a “traitor to the fatherland” 30 years later. In that country, any Jew could be a traitor – one who loved the homeland, as my father did, and one who did not love it, as I did.

In 2001, on a flight from Tel Aviv to Geneva, on my way to work in France, I wrote the poem “My Heart in the East.” Fans of Jewish poetry know that this line is the title of a poem by Halevi.

Judah ben Shmuel Halevi was a Spanish Jewish poet, physician and philosopher. Halevi’s poems of longing for Israel like Libi baMizrach (“My heart is in the East, and I am at the edge of the West”) juxtapose love and pain, and dream and reality to express the distance between Spain and the Middle East and his desire to bridge it. Among his many poems celebrating the Holy Land is “Zionide” (“Ode to Zion”), his most famous work and the most widely translated Hebrew poem of the Middle Ages. He lived in Spain under Arab rule, suffered from the country of Israel being under Crusader oppression, and dreamed of a homeland for the Jewish people:

My heart is in the east, and the rest of me at the edge of the west.

How can I taste the food I eat? How can it give me pleasure?

How can I keep my promise now, or fulfill the vows I’ve made

While Zion remains in the Cross’s reign, and I in Arab chains?

With pleasure I would leave behind all the good things of Spain,

If only I could gaze on the dust of our ruined Holy Place.

My attraction to Halevi’s poetry was explained by the American-born Israeli writer and journalist, my comrade-in-arms, Hillel Halkin, who was wounded while our infantry battalion was fighting in the First Lebanon War in 1982: “Can we call Halevi the first Zionist on this basis? This question relates not so much to Halevi as to the nature of Zionism. Halevi was certainly not the forerunner of the Zionism of Theodor Herzl, who dreamed of establishing a sovereign Jewish state in Palestine – in Halevi’s time this goal was completely unattainable. We have no reason, following Bauer, to consider Halevi a political thinker. However, if one considers Zionism to be the belief that the return to Zion is the supreme value to which the Jewish people must aspire for its own sake, then Halevi may well be called a “proto-Zionist.”

In the poem “Yehuda ben Halevi” in the collection Romancero (Romances – 1851), Heinrich Heine wrote about Halevi:

Yes, he was a mighty poet,

Star and beacon for his people

And the light of that whole era,

An immense and wonderful

Pillar of poetic fire

Moving out in front of Israel’s

Caravan of grief and anguish

In the wilderness of exile.

I saw in a Jewish poet a person who loved the country of Israel and was eager to repatriate. I wrote my poem not about Halevi, but about myself, but based on his poetry and in his native language, Hebrew. My friend, the Israeli composer Boris Levenberg, wrote a melody to this poem. Our song was placed in the compilation of the Israel Composers Union and was played on several CDs, in a number of auditoriums and in an amateur film. I am not a translator, so I cannot make a poetic translation of my poem into English. I can only retell it, and only partially, to give a sense of the author’s mood:

At the crossroads of oil routes,

Among the sandy whirlwinds

Lives in white and blue

A little country

A piece of land in the East,

You’re no longer a legend

The air in your mountains is pure.

My melody is your melody.

Chorus

Land flowing with milk and honey,

Country flowing with milk and honey,

Land that dreams of the future,

Land of the Pentateuch,

The country that makes noise in the world,

The land I’ve chosen forever.

Two thousand years of separation from you

Are imprinted in my heart.

Six million dead

Live in my soul.

Wisdom comes late.

Oil is worth more than blood

Hell reigns,

No recognition of the value of man.

My heart beats in the East.

I come back from the West

Dreaming of my country

And a golden Jerusalem.

On the shores of the Mediterranean Sea,

In the midst of war and peace

I found my place, not riches or peace.

At last my dream came true.

The rhymes of the original Hebrew have disappeared when translated into English. They are not like the rhymes in Halevi’s poems. “Zionides” of the Jewish poet, his poems were close and consonant with me, but my poem about Halevi was autobiographical. Our song “My Heart in the East” was sung by several singers and played in an amateur movie. I bring here a recording of the song performed by Nofar Yehuda, a young student of the composer. After performing the song, the singer wrote to me that she thanked me for the piece that had spiritually enriched her life.

I remembered this joyful song to lift my spirits on the sad Sabbath of October 7, 2023, the day that instead of the “Joy of Torah” holiday, it was a mourning Sabbath in Israel, for a Jewish pogrom was carried out. On that day, many Israelis felt a sense of being Jewish. This feeling was generated by the worst Jewish pogrom since the Holocaust. The memory of former joy that beats in the song warms the soul and softens the bitterness of sad days. Although the song is written in major and sounds joyful, it has lines that accurately describe the events of October 7, 2023:

Oil is worth more than blood

Hell reigns,

No recognition of the value of man.

*

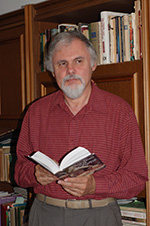

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education.

Thank you for this interesting and insightful piece, and for your heartfeld poem. Truly uplifting.