E ditor’s Note: This is the 17th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

ditor’s Note: This is the 17th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Volume 3, Exit 44 (La Costa Avenue) Chabad of La Costa.

From northbound Interstate 5, take the La Costa Avenue exit and turn right. Proceed beyond Batiquitos Lagoon to domed building at 1980 La Costa Avenue on the left-hand side of the road.

CARLSBAD, California – For Rabbi Yeruchem Eilfort of La Costa, the world was dramatically changed when he was 12 years old.

CARLSBAD, California – For Rabbi Yeruchem Eilfort of La Costa, the world was dramatically changed when he was 12 years old.

Growing up in an upper-middle class home in Palos Verdes, California, a terrible family tragedy occurred. His schoolteacher mother, Ronnie, was killed in an automobile accident. Not long afterwards, his father David Heinz Eilfort, a patent attorney, decided to move the family to Irvine, California, so as his children’s only parent, he would spend less time commuting between home and work.

The Eilforts left Temple Menorah, a Reform congregation, and the Palos Verdes school system for Irvine. The oldest son, William, was 16, and Yeruchem, then known as “Jerry” was 12. Even though their father’s commute time was shorter, they often were “latchkey kids,” who had to take care of themselves while their father worked.

Following the suggestion of a friend, David enrolled his younger son in Camp Gan Israel, a Chabad day camp in Huntington beach, while William made ready to attend a secular college and eventually to become the successful designer of logic questions for the LSAT (legal scholastic aptitude test) and other exams.

The younger Eilfort did not want to go to the camp; he wanted to spend his summer at the beach. However, “that changed the first day I was there,” Rabbi Eilfort told me during a May 2022 interview. “What happened was that I had a paradigm shift. A light went on. Judaism was not just a subject that you went to study in a classroom or at the synagogue where you put on a kippah and then went home and back to other things.” Judaism, he realized is a whole immersive way of life. “I saw all these really friendly kids who put their kippah on, and we played football with a kippah on, we went bowling with a kippah on, and we played Pacman with a kippah on. Judaism is not just a subject; it is a life. It spoke to me in a big way. I felt this connection, this camaraderie, that Judaism is dynamic, that it is relevant, and everything felt right to me.”

One day, Eilfort saw his father accept a brochure from Rabbi Moishe Engel about the Chabad Hebrew Academy in Huntington Beach. “I went ballistic,” he recalled. “I was really looking forward to going to the local high school in Irvine. I asked my father to not even think about enrolling me at the Chabad school. But two weeks later, I was asking if he still had the brochure. Wow! Talk about a difference: instead of being one student among 25 or 30 with all the stories you hear about high school cliques, the Chabad Hebrew Academy had much smaller classes and everyone was buddies with everyone. Not everyone was Orthodox, in fact most of the students weren’t, but they came from homes where their parents felt that they should have a strong Jewish education or that their kids should be more sheltered. There is a certain innocence of kids in the Jewish schools that is not in the public schools. I saw that firsthand.”

With his father working and his brother in college, Eilfort made strong, family-like connections at the Chabad school. His teachers had “time for students, friendliness. They would invite students over to their homes for a Shabbat with a couple of friends. They would have a Shabbaton (Shabbat weekend with prayer, study, and activities) and trips. All the different extracurriculars were just as exciting to me as the subjects I had never heard about like Talmud, and I started studying. At first, I was a smart aleck. I said, ‘What difference does it make what your cow does whatever? – I don’t have any cows!’ The rabbi said, ‘It is not just the cow. It is the idea of possession/ ownership and there are different types of possessions. There are moveable objects. There is real property.’ And the light started to go on.”

At home, Eilfort discussed Talmud with his father. “It appealed to my father’s intellect and to my father’s legal mind, the way he analyzed issues and the way he approached things. We had great conversations, he and I. He was in this dark place (following his wife’s death) and having these conversations with me helped lift him out of it somewhat. He got such nachas (joy) out of these conversations. It was intellectually stimulating, but he also saw the incredible value of learning how to make a blessing, of taking nothing for granted, of being grateful for things. It is not just when you feel like saying ‘Thank you.’ In this life, you have to say ‘Thank you.’ You say ‘Thank you’ to God and “Thank you’ to people. It is drilled in. It is a different mindset.”

Classroom lectures alone did not influence Eilfort to follow a more religious life. He also witnessed the example of Rabbi Mendel and Mrs. Rochel Duchman, a young couple who established a Chabad house in Irvine. “They started a minyan (prayer group) in their house, and it grew and grew. I was one of the regulars and they adopted me like I was their own. They invited me to every Shabbos meal. I didn’t always go, but they were very warm with me, and I helped. I pitched in. For example, they had a Shabbat Club on Saturday afternoons for kids, and I helped. I was an older kid, a junior counselor type. They were so dynamic, so positive, so loving, that I thought this is a good way to spend one’s life. I knew pretty quickly that this was what I wanted to do.”

Eilfort was invited to a Shabbaton at Yeshiva Ohr Elchanan (Light of God’s Graciousness) Chabad in Los Angeles, and “it was great on steroids!” He decided to continue his education at the Los Angeles yeshiva, which in turn led to him following graduation to study at the Rabbinical College of America in Morristown, New Jersey, for the rabbinate.

“Chabad has an interesting system,” Eilfort reflected. “When a student is considered a senior student, they send hm to help in yeshivas around the world, to help younger yeshiva students. I was in Morristown for a year and then to a yeshiva in Miami Beach, Florida, and that is when I started studying for smicha (rabbinic ordination). The senior rabbi, head rabbi of the yeshiva in New York, would test people and he would give you rapid-fire questions about Jewish law. My study partner today is here in San Diego teaching at the Chabad Hebrew Academy, Rabbi Yisroel Dinerman. We flew (from Miami) to New York a couple of times to get tested. There was a series of four tests we had, three of them at 770 (the address on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, which is the headquarters for the Lubavitcher movement), and another at a Rabbi Piekarski’s shul in Queens. It was very informal. It was just us and one other guy and he grilled us!”

Whenever Eilfort was in New York, he would visit the Chabad headquarters at 770 to attend audiences with Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Rebbe of the Lubavitcher Chasidic movement. “The Rebbe used to have farbrengens – Chassidic gatherings – almost every Shabbos and several times during the week,” Eilfort said. “I would go to those pretty regularly. I was blessed with a strong exposure to the Rebbe and certainly his teachings were studied thirstily at the yeshiva, You wanted to see what he said about this and that. The Rebbe’s scholarship and brilliance were just amazing. You study a Torah portion, you see what various commentaries say about it, and he would tie them all together.

“What struck me about the Rebbe’s teaching and what I try to emulate was the way he would make it relevant to us in our circumstances now,” Eilfort said. “His encyclopedic knowledge and his scholarly creativity were breathtaking. He was able to connect current events with Torah powerfully. He would always take the broad view of things. He would be able to explain why this portion (of the Torah) was next to that portion, and how this response to what we learned in the Code of Jewish Law or in Maimonides or in the Talmud all tie together.

“The most important thing that struck me, and continues to, was his absolute complete love of every human being. He had a passionate love of people that shone through, and you could just feel it. You could feel how he valued you as an individual. He spoke to every person individually like there was no one else in the room, as if he had nothing else to do with his time. There is a saying: ‘words that come from the heart enter the heart.’ When you are sincere, the sincerity will be felt by the other person, and it will have an effect on the other person.”

Eilfort remembered marveling how the Rebbe in his last years “would stand for hours and hours on a Sunday and anyone who wanted a blessing would come. He wouldn’t have a long time to speak to each person, but he would give him a blessing. He also gave each person a dollar. Why? Because he taught that when two people meet, they have a mandate to help a third person. That is the number one thing that they should be thinking about. ‘This dollar that I am giving you, be my emissary and give it to charity, or find someone who needs it.’ So, every Sunday, thousands and thousands of people would line up to get their moment with the Rebbe. They would ask him, ‘Don’t you get tired?’ And he replied, ‘When one is counting diamonds, one does not get tired.’ It was invigorating, empowering, energizing and it made you feel that there is something greater than us as individuals; that we can do great things together.”

Eilfort’s final test for smicha was the first test administered by Rabbi Labkowski. On Eilfort’s 22nd birthday he passed. He flew to California for a visit with his father and to assist Rabbi Duchman. While there, he heard that Rabbi Labkowski had decided a fifth test should be given. Rabbi Labkowski told Eilfort until he took the fifth test, he didn’t have smicha. I said, ‘Do you think that is fair? Are you saying that all previous smichas are invalidated? If you backtrack on me, you will have to backtrack on everyone!’ So, I prevailed. Rabbi Dinerman picked up my certificate for me.”

After receiving his smicha, Eilfort followed the custom of announcing his intention to get married. “It is all done through the shidduch (arranged marriage) system,” Eilfort related. “What happened was that a rabbi knew my future wife (Nehama Israel) well because she had worked for him at a summer camp. My future mother-in-law was scouting the ranks at 770 for her daughter. She found out about me. She told my wife’s rabbi back in Palo Alto, Rabbi Levin, and he made a call to Rabbi Duchman” and through these intermediaries, it was arranged the couple should go out on a date in New York City.

“I was supposed to pick her up in front of her house,” Eilfort related. “I borrowed my friend’s car. There was no GPS in those days so I learned the directions in advance. I did a dry run; I left nothing to chance. I had no idea what she looked like; it was literally a blind date. I came at the appointed hour, and she was running late. She had only heard that day she was going out that night. It was her mother who arranged it and she didn’t want to go. She was going to Touro College at the time, and she enjoyed hanging out with her friends. She gets in the car, plops down on the seat, and says, ‘Tell me about yourself. I know nothing about you.’ Like that, with a chip on her shoulder. I was taken aback by her attitude, so I had to do something. I joked – that is my way of relieving tension. I took a line out of the Steve Martin movie, The Jerk, and I said, “I was born a poor Black boy in Mississippi’ and she started laughing and that broke the ice and the tension.”

Dating typically was conducted in very public places. They chatted in hotel lobbies and walked around South Street Seaport.

“We definitely hit it off,” the rabbi reminisced. “I had gone out before, and the conversations had been almost laborious. Not this time. It just flowed like electricity between us. I am talking about intellectually. Before I knew it, five or six hours had gone by and we thought, ‘Oh, we have to go home.’ She broke one of the biggest rules. She said, ‘I had a good time; I’m looking forward to going out again.’ You’re not supposed to say that. You are supposed to do it through a shadchan (matchmaker) because you don’t want any emotions or chemistry. At this point, you want it to be purely ideological. Later there is time for that. You have to be very calculating almost: ‘Is this the person for me? Does she check off the boxes?’ For me and for her, it was love at first sight.” Eilfort proposed on their sixth date. They were married several months later.”

Nehama Eilfort, who today is the Rebbetzin at Chabad of La Costa, “is extraordinarily brilliant, so smart it is scary,” her husband said. “A photographic memory, loves to learn, and she retains everything she reads. She knows medicine like a doctor knows medicine. If a child falls down, feels pain, people will call her, she knows exactly what to do. She knows Toras inside out. She loves helping people. She is my full partner at the shul.”

The couple decided that they wanted to open a Chabad House somewhere. Immediate opportunities were available in Alaska, Arizona, California, and Greece. The weather of Alaska and Arizona seemed respectively too cold and too hot, and Eilfort doubted he could learn the language of Greece. On the other hand, San Diego County was ideal because Elfort had worked in San Diego during a summer break as a head counselor at Camp Gan Israel under Chabad Rabbi Yonah Fradkin.

Rabbi Fradkin “said he wanted to open a Chabad center in the North County Coastal area and that Nehama and I might be the two to do it,” Eilfort recalled. Fradkin advised Eilfort to build slowly. He gave him a half-time job at the local Chabad headquarters, then located near San Diego State University, leaving time for the Eilforts to start making known their desire to serve the region stretching north from Encinitas to Oceanside. Their first year they lived in a house near SDSU that they rented from Gussie Zaks, a beloved Holocaust survivor who almost up until the time of her death spoke at schools and synagogues about her experiences.

From that base, they started reaching out to the Jews of North County. “Two things happened simultaneously,” Eilfort reminisced. “There were some people involved with Chabad in University City with Rabbi [Moishe] Leider. It was a big extended family with a couple of brothers with a bunch of kids of varying ages, but not little kids. They were very devoted, very traditional and they wanted something close, so when we came up, they were very excited. That is the Perez family from Morocco. Right there it was almost a built-in congregation. Aside from that, my wife and I went to the public library, and we found the phone book and started calling Jewish-sounding names from the phone book. We started with having a parlor meeting to introduce ourselves to the community, to say we wanted to come here to get something started and we had a nice response, maybe 30 people came. It was right in the summer of 1989, and we said we’re thinking of High Holy Days. They said, ‘Yes, let’s do High Holy Days,’ so we rented a hotel to do High Holiday services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.”

“Then we started doing Hebrew school for a family that had kids up in Oceanside,” Eilfort continued. “We drove up there a couple times a week. We held school in someone’s living room; it started with two kids and it grew to six kids and so on. Then we were doing services starting in January, first at one Perez brother’s house and then at the other’s; then at a third place. And they invited friends. So, after about six months of doing services there, they said, ‘Move up here (to North County), Rabbi, and we will do services in your living room.’ So that is what we did. It went very well. The little kids all came and hung out with our kids, and the kids played together, and the moms met together, and the dads went over to the side and davened (prayed). It was a family dynamic, very positive, beautiful, and simple.”

After the Eilforts held services in their rented home, the next big stage was renting a building at 1980 La Costa Avenue which originally had been used as offices during the construction in the mid-1960s of the nearby a Costa Resort. That building later was used as a preschool, then a church office, and subsequently was occupied by squatters. The Eilforts were able to rent it for $500 a month, provided that they took care of all improvements.

“A Chabad Center is perhaps unique in that the entire family is intimately involved in running it,” Eilfort said. “Judaism is organic in our lives; it is not simply a subject that we decide to open a book about and learn about once a week. It is our constant companion. We live with the Torah and the mitzvot (commandments). There are times for formal services and formal classes and gatherings, which would be in common with any other place. It is just the organic nature of it that might be a little bit different.”

“The Rebbetzin, for example, is just as much an integral part of it as I am,” Eilfort explained. “She is here when I am, especially at services and events. Sometimes she teaches a class, sometimes I teach a class. We are partners in this. We are co-directors. I might be a little more visible, but that makes her no less a part of it and a leader of it. I always laugh when people say Orthodox relegate women to secondary roles. Not in Chabad, baby! It is just not the truth. The rebbetzin is the soul of the place and that is not unique to our house. The children are part of it too. They grow up in shul running around, and now, for us, our grandchildren do. It can be a challenge to one’s patience while you are trying to run a service and they are playing tag, but the better part of me says what an incredible blessing that I am living my lifestyle and here my grandkids are with me. The grandkids are with me because the kids are with me.”

The Eilforts have eight children, who in May 2022 ranged in age from 32 to 15. In birth order, they are Elia, Yossi, Rivka, Chava, Muka, Mendel, Sholom, and Dovid. Elia, now a rabbi himself, built Chabad of Encinitas with his wife Chaya, while helping his father plan for a preschool in Carlsbad. Yossi and his wife Dassy have started Magen Am (Shield of the People), a self-defense group in Los Angeles that “works very closely with the police and other law enforcement agencies.” Rivka and her husband Yona Fenton live in New Haven, Connecticut, where she teaches at a Chabad school, and he is in private practice as a family counselor. Chava lives with her husband Benyamin Klipper, where ahe is a medical assistant, a phlebotomist and a dula (birth coach). Muka and her husband, Rabbi Yossi Rodal, have settled in the northern part of Carlsbad, where they lead the Friendship Circle, a Chabad-sponsored activity group for people with disabilities. Mendel, Sholom, and Dovid were unmarried, with Mendel attending Mira Costa College; Sholom a rabbinic student in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and Dovid, the youngest, a student at Southern California Yeshiva (SCY) High in San Diego.

As Chabad of La Costa grew, benefactors contributed sufficient funds to purchase the land, tear down the old building, and construct a modern synagogue. “We started the project during the great recession,” Eilfort said. “There were plenty of professionals available in those days. They were hungry. They were looking for work. Our architect was Robert Richardson, a wonderful guy who is a Judeophile and likes finding biblical references and that kind of thing. He said ‘Okay, this is the dream stage. Tell me everything you want.’ So, I had a list ready for him. He said, ‘Rabbi you have 20 pounds of groceries in a 5-pound bag, but okay let’s see what we can do.”

Eventually, they built a 7,000-square-foot basement for future development, and a 5,500-square-foot main floor that includes a sanctuary; a 400-square foot kosher (meat and pareve) kitchen, offices, library, bathrooms, and a breezeway, or atrium, in the middle “which gives it an indoor-outdoor feeling” with a deck overlooking Batiquitos (Shallow Watering Hole) Lagoon.

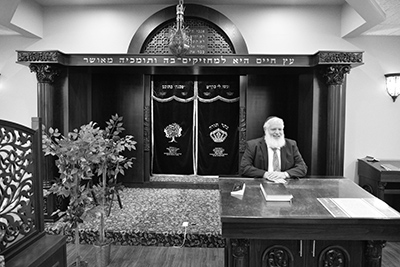

The sanctuary is Rabbi Eilfort’s pride and joy. “It has beautiful custom-made furniture built in Israel at Kibbutz Lavi,” he said. “They sent it here in a container and then they sent a team to assemble it. The ark is magnificent, an entire structure. One of our supporters, Channah Hale, commissioned some stained-glass windows” made by Leslie Thieda of Elegant Glass. “The windows have Jerusalem scenes on them. One has the Western Wall and areas around it. The other is a more pastoral scene with pomegranate trees. Then we have a beautiful eternal light, a very Old-World feeling. The Brunelle family sponsored the furnishings.”

About the kitchen, Eilfort commented: “The amount of food that comes out of this place you would not believe. We must have produced millions and millions of calories over the years. On Fridays, we send out chicken soup and challahs to people in need. We do beautiful Kiddushes (afternoon meals following Shabbat services) every week, and during the summer we do restaurant nights for people who are visiting or who want to have a kosher restaurant experience with a view of the Batiquitos Lagoon.”

The next phase will be to complete the basement, with areas for a preschool, teen lounge, additional classrooms, and a “Children’s Holocaust Library” which will be donated, Eilfort said.

“We always want more people,” Eilfort said at the conclusion of our interview. We are warm and welcoming. We love when people visit on Shabbat morning at 10 a.m. Our service is over about 12:30 and it is followed by a kiddush lunch.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.