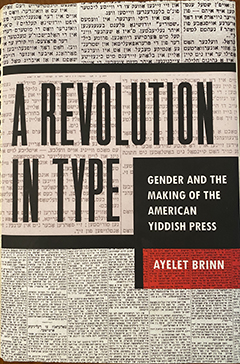

A Revolution in Type: Gender and the Making of the Yiddish Press, Ayelet Brinn, New York University Press, 2023, 315 pages.

By Oliver Pollak

RICHMOND, California — This astonishing and extraordinarily well researched book is the origin story of the American Yiddish press, its evolution and feminization.

RICHMOND, California — This astonishing and extraordinarily well researched book is the origin story of the American Yiddish press, its evolution and feminization.

The golden age of the American Yiddish language newspaper is from the mid-1880s to the mid-1920’s. Its popularity and profitably was driven by massive immigration of Jewish Yiddish speakers from Eastern Europe to New York. Between 1870 and 1914 the number of Jews in New York almost doubled, from 800,000 to almost 1.4 million. “New York-based Yiddish daily circulation jumped from about 375,000 in 1912 to almost 540,000 by 1916,” sometimes exceeding the New York Times circulation. The passage in 1924 of the Johnson-Reed Act introduced restricted immigration based on national quotas started a long slow decline.

Before radio, newspapers were the main vehicle for disseminating local, national and international news. They were instrumental in the immigrant transition of Americanization, acculturation, acclimation, assimilation, acquiring citizenship, and the emergence of the first generation of English speakers.

The Forverts, founded in 1897, was not the first Yiddish paper, but it was the pacesetter. The Forward went from Yiddish to Yiddish and English, and in 2019 discontinued its print edition and went online. Yiddish newspapers supported various ideological positions including Socialist, Communist, Marxist-Zionist, anarchist, and nonpartisan.

Brinn reveals that the Yiddish press underwent a process of feminization as the publishers and editors reached out to women to expand readership, circulation, subscribers, and advertising revenue. Women made the economic decisions about household purchases. This transformed content and presentation to include the women’s column, women’s page and greater use of women writers. The newspapers gave a platform for Yiddish novelists, poets, short story writers, editors, publishers catering to an expanding and gendered Yiddish newspaper reading market.

The Yiddish newspapers translated stories from English language newspapers. The author suggest translators were frequently women whose education included English, Yiddish, German, Russian, and French, while the religious education of male Yiddish speakers concentrated more on learning Hebrew.

Men sometimes, without their editors’ knowledge, perpetrated a ruse or deception by writing with a feminine byline. Women also employed male pseudonyms. Women’s columns and the Women’s Page included human interest, advice columns, serialized fiction, feature stories, entertainment, child care, nutrition, cooking, recipes and food, housekeeping, fashion, clothing, love, romance, birth control, humor, theater, suffrage and voting rights, public schools, directed at women but also read by men.

Before American entry into WWI the Yiddish press either championed neutrality or supported the Central Powers, being unwilling to support an alliance that included the tsarist regime. The entry of the United States into the War, the Russian Revolution and Russian withdrawal from the war led to newspaper support for the Allied cause.

Brinn raises the curtain of the Yiddish newspaper industry infrastructure in a revelatory manner. Researching “behind the scene,” she identifies the role and status of women as contributors to the press, how to speak to female audiences, and the feminine consumer audience to which it is directed. Much that is written is anonymous, unsigned and unattributed but may have been written by women. Bylines and pseudonyms may not be reliable identification of gender. Women tended to be freelance writers with lower compensation and job security than employed staffers. They slowly ascended to staff, editorial staff and subsequently editors.

Brinn is at her best as a literary scholarly detective as she discloses the mysteries of authorship, especially as she takes a deeper dive in Laura Z. Hobson author of Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and First Papers (1964) whose parents were the prominent Yiddish journalists Michael Zametkin and Adella Kean Zametkin.

I recommend this book to those interested in the history and culture of newspapers. Yiddish newspapers had inflection points which we continue to observe and experience in our own newspaper and book purchasing environment. The bibliography, itself worth the price of the book, includes Berl Kagan’s 1986 work listing almost 6,000 pseudonyms employed by Yiddish writers and other vital and alluring books and journal articles. The depth of Brinn’s research is scintillating with thrilling discoveries. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research provided the main archival collections. The bibliography lists 20 Yiddish language newspapers.

The author is the Philip D. Feltman Assistant Professor of Modern Jewish History in the Department of Judaic Studies and History at the University of Hartford. She received her doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania with the dissertation, “Miss Amerike: The Yiddish Press’s Encounter with the United States, 1885-1923.” Your reviewer’s introduction to Brinn’s scholarship occurred in a late February 2024 zoom presentation which inspired him to acquire this award-worthy book.

*

Oliver B. Pollak, Ph.D., J.D., professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, a lawyer and a member of the Institute for Historical Study, is a San Diego Jewish World correspondent based in Richmond, California.